This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

Become a subscriber today!

Register

When is a fixed election date not a fixed election date? When you seemingly disregard a set-in-stone rule and attempt to set a new date for an election that’s more to your liking.

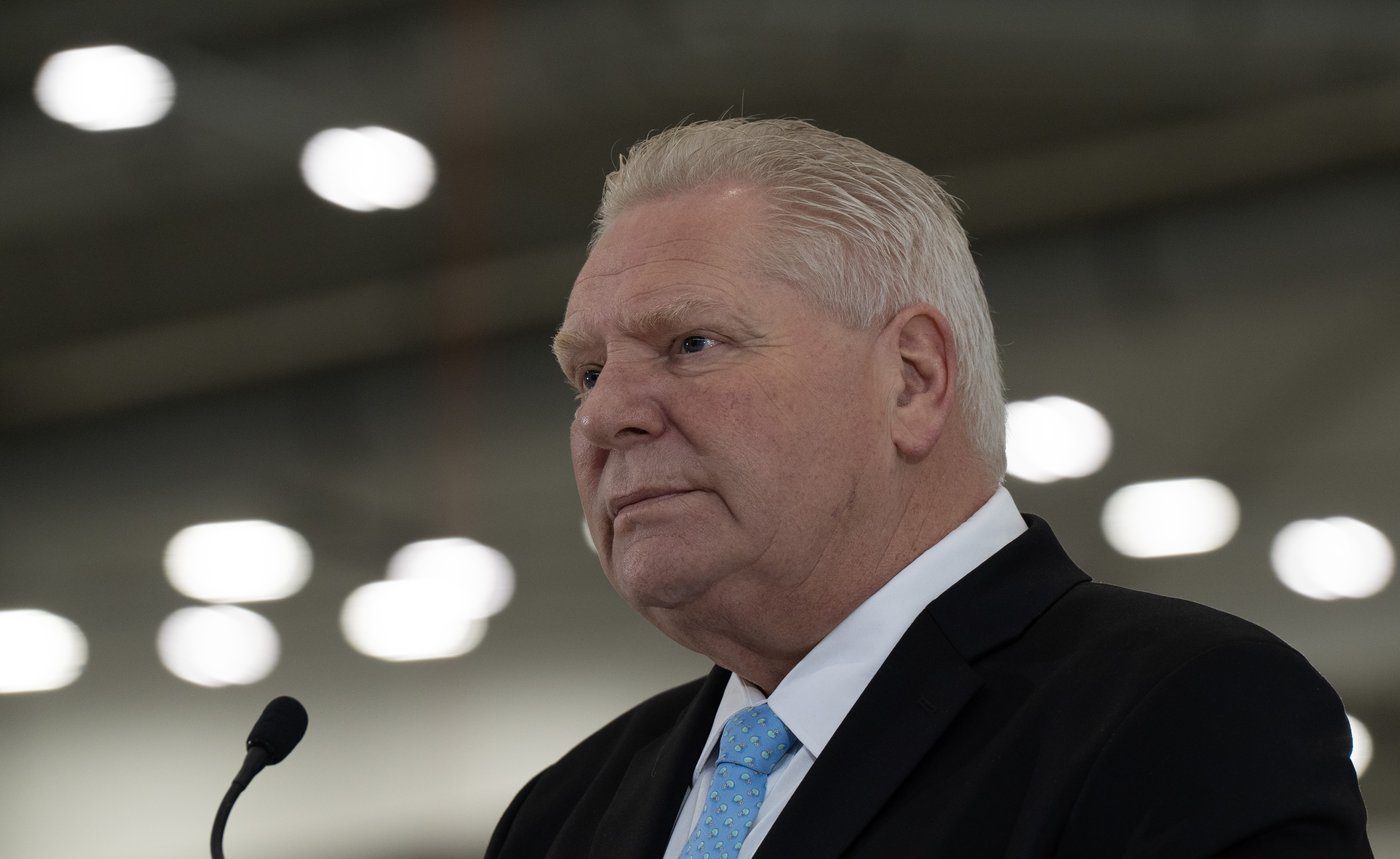

That’s what some Ontarians may have thought when they heard Premier Doug Ford was thinking about an early election call. Or was something completely different at play? I believe it’s the latter.

Ford is reportedly “considering an early election call before the scheduled 2026 vote over concerns about cuts a future federal Conservative government might impose,” according to the Toronto Star’s Robert Benzie and Rob Ferguson. “Sources say Ford is worried that if, as polls suggest, Pierre Poilievre wins an election expected in October 2025, there would be reduced transfer payments to the provinces,” they wrote on May 28, which means “a scrapping of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s electric-vehicle strategy that is a cornerstone of Ontario economic policy and other slashed spending that would hurt the Progressive Conservatives.”

There’s the added belief a federal Conservative government would help the electoral fortunes of Bonnie Crombie and the Ontario Liberals.

This follows Prof. Frank Underhill’s theory that Ontario voters prefer having different federal and provincial parties in power simultaneously. “In the 1870s and 1880s and early 1890s many a good Ontario citizen would vote Grit in provincial politics,” he wrote in the now-defunct Canadian Forumin 1946, “and then, appalled at the thought of Grit domination of the whole of Canada, he would turn around and help re-elect [Sir John A.] Macdonald in federal politics. Just so today. Thousands of Ontario voters last summer, after putting Mr. [George] Drew into office, turned round within a week and helped the rest of Canada to make sure that Ontario tories should not dominate the Dominion.”

Underhill’s balance theory had historical merit. This concept has largely dissipated, however. Ontario voters have moved away from a need for political balance to a desire for ideological consistency. Voting for a federal Conservative government and provincial Ontario PC government, much like voting for a federal Liberal government and Ontario Liberal government, is gradually becoming the norm rather than an exception to the rule.

If Ford and his senior advisers are worried about this, they shouldn’t be.

Benzie and Ferguson also suggested an early election call is a “major reason why the premier is paying the Beer Store $225 million to liberalize booze sales as of this fall.” That’s more than a year ahead of schedule, which some of Ford’s critics claim “could actually cost taxpayers between $600 million and $1 billion.”

Ford didn’t address or commit to holding a planned provincial election in June 2026 during last week’s announcement about the Beer Store. He simply stated, “I just want to get our agenda through.” When Toronto radio host Jerry Agar pressed Ford on May 28 about the possibility of an early election call, the latter told him, “again, I can’t answer that. I just can’t right now.” Agar responded, “well, who else can?,” which led to the Premier’s retort, “Jerry, Jerry, as far as I’m concerned we’re going to focus on our agenda, getting things done and the people are going to decide – that’s what’s beautiful about a democracy.”

Ford also added this small statement, “stay tuned.”

Hold on. Why should Ontarians stay tuned if he can’t call an early election? The Election Statute Law Amendment Act, 2005, which was passed by then-Premier Dalton McGuinty and the Liberals, noted that provincial elections held after Oct. 4, 2007 would be scheduled “on the first Thursday in October in the fourth calendar year following polling day in the most recent general election.” This has been adjusted twice. The 2007 election was shifted to Oct. 10 because of the Jewish holiday of Shemini Atzeret, and the Election Statute Law Amendment Act, 2016, switched it to “the first Thursday in June in the fourth calendar year following polling day in the most recent general election.”

Ah, but there are some exceptions to fixed election dates.

The most obvious is a minority government situation. Political parties in Canada with less than 50 percent of seats in a federal or provincial legislature typically last about 18 months. Formal and informal coalitions with other parties can extend their stay. The three year work-and-supply agreement between the federal Liberals and NDP has given Prime Minister Justin Trudeau an additional lease on life. Generally speaking, however, a fixed election date for minority governments is a near-impossibility.

Ford doesn’t have to worry about this situation. The Ontario PCs won successive majority governments in 2018 and 2022. The latter is one of the largest majority governments in Ontario’s history.

That being said, Ontario’s election law includes the following passage, “Nothing in this section affects the powers of the Lieutenant Governor, including the power to dissolve the Legislature, by proclamation in Her Majesty’s name, when the Lieutenant Governor sees fit.” If an Ontario Premier with a majority government could convince a Lieutenant Governor that an early election was necessary, the fixed election date could be bypassed.

Is this what Ford is trying to do? I don’t believe so.

It’s more likely the Premier is stirring the pot to make people think a snap election is possible. A touch of smoke and mirrors in politics isn’t unusual, after all. Or, he’s simply trying to give himself a leg up on present and future negotiations with Trudeau and, at some point, Poilievre. That’s not impossible to believe, either.

Either way, it gets people talking about Doug Ford’s Ontario, political machinations as we get closer to summer – and whether fixed election dates actually make a difference.

Michael Taube, a longtime newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

In a spring 2023 report on last June’s provincial election, Ontario’s chief electoral officer Greg Essensa has urged that in future “no public opinion polling results stating political party favourability ratings be published in the final two weeks before election day.”

Briefly, popular perceptions that the results of a coming election are already known through ubiquitous polling are arguably bound to “demotivate” voter turnout. And the argument here has been largely motivated by the stark fact that in 2022 only “44 per cent of Ontarians cast their ballot, marking the lowest recorded voter turnout in the province’s history.”

Just after the release of the Ontario report the April 3, 2023 provincial election in Prince Edward Island similarly had “by far the lowest voter turnout of the last six decades.”

As in Ontario in 2022 in PEI in 2023 a “Progressive Conservative” government was re-elected with a strong majority of seats. (At the same time, “low turnout” in PEI was not quite 69%!)

Pollsters are bound to disagree with any polling ban. Whether polling does anything worse than sometimes exaggerate what is already there in the human political drama may equally be a question raised by the now rather long history of Ontario voter turnout.

Chief electoral officer Essensa’s Elections Ontario also publishes an online table of voter turnout and allied data for all 43 general elections in the province since confederation in 1867.

At the start of the story it is worth underlining a big change in 1919. Ontario became the fifth Canadian province to give women the vote in provincial elections in 1917. The October 20, 1919 provincial election was the first contest with this major addition to the voters list.

The 1919 election was unusual in a few other ways. In 1911 the province’s urban population had for the first time exceeded its rural population. And then unusually large numbers of young urban and rural Canadians had lost lives in the First World War that ended in 1918.

On October 20, 1919 the people of Ontario elected what would become Ernest Charles Drury’s unusual “Farmer-Labour” third-party government of 1919-1923. And in the current Elections Ontario table the 1919 election marks the high point of voter turnout down to the present.

Meanwhile, declining voter turnout since 1919 is nothing new! There were 14 Ontario elections from 1867 to 1914, another 14 from 1919 to 1967, and then 15 from 1971 to 2022. Average voter turnout has fallen consistently over these periods — from a 69% median for the male electorates of 1867–1914, to 65% for the all-adult electorates of 1919–1967 and 58% for 1971–2022.

Part of the explanation may be reflected in present-day differences between a still comparatively rural Prince Edward Island (with a historic low of 69% turnout in 2023) and an increasingly urbanized Ontario (with a record low turnout of 44% in 2022).

The record for the most recent 15 Ontario elections from 1971 to 2022 similarly shows continuing decline. The high point comes at the start of the period when almost 74% of the electorate turned out for Premier William Davis’s first election of 1971. Then turnout slipped to 68% in the 1975 election and 66% in 1977.

At the other end of the scale, the second lowest turnout (after the record 44% just last year) came in Premier Dalton McGunity’s last election of 2011, when less than a majority of the electorate (only 48%) actually voted for the first time since 1867.

Turnout was only 52% in the 2007 and 2014 Ontario elections, and 57% in 2003 and 2018. The seven of the last 15 elections with turnout over 60% were all in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. And the median voter turnout for the six elections of the 21st century so far is a mere 52%.

Since the advent of the present-day all-adult electorate in 1919 Ontario voter turnouts of more than 70% have been confined to the wakes of the two world wars in 1919 and 1945, the 1930s Great Depression (1934, 1937), and the 1971 election at the close of the 1960s age of change.

Whatever else, the trend toward lower and lower voter turnout, underway since the First World War and the fading of the old family farm democracy (with its largely all-male electorate), probably is rooted in something deeper than the impact of opinion polls in the final two weeks of an election campaign.

The people of Ontario may have to think a little harder about their provincial parliamentary democracy today to figure it all out.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

The Ontario election campaign has come to a close. It’s been over a month since the results came in. This means the Liberals have had time to reflect on their poor performance, the NDP has had time to reflect after their leader resigned, and obviously, the Progressive Conservatives have had time to name their new cabinet and new Parliamentary Assistants.

The Ontario Liberal Party hasn’t yet named a new Interim Leader, following Liberal Leader Steven Del Duca stepping down as leader of the party. Del Duca as leader of the party undoubtedly did things that perhaps other leaders wouldn’t have been able to do, such as pay off the party’s debt. However, there were most definitely questions as to his performance, only winning the party eight seats in the legislature and not evening winning his own riding of Vaughan-Woodbridge. The riding of Vaughan-Woodbridge has always been a toss-up riding, of course, it’s held federally by Liberal MP Francesco Sorbara and provincially by Michael Tibollio from the PCs, who of course is an Associate Cabinet Minister in the Government. Tibollio defeated Del Duca in 2018, and he did so again in 2022. The Liberals will need to do much reflection, which of course is something Liberal insiders and strategists are already doing. The party will need to pick a new permanent leader before for the next provincial election. It’ll need to be someone who can appeal to audiences specifically which Del Duca wasn’t able to do. The party is likely still recovering from the 2018 campaign, which was quite devastating for the party, and so no matter who was the Leader of the party, it still probably would’ve been a challenge to attract the groups of people Del Duca wasn’t able to do.

Del Duca didn’t make the number of gains he needed to in the GTA. Historically the GTA is generally where progressive parties such as the Liberals have their most success. There were also many examples of how Ontario’s system is designed to elect individual MPPs for each individual riding, such as Barrie-Springwater, a riding where the former Mayor of Barrie, ran against the incumbent Attorney General and MPP, where the former Mayor came in very close considering this riding is usually seen as a safe PC riding in the legislature. There were also many ridings, which some local candidates admit they could’ve had better organization and better ground game, ridings such as Ajax, Mississauga Streetsville, or even University-Rosedale. It can’t be read into very much though, nevertheless because the election was a contest of name recognition and the PC Leader had been on everyone’s television screen nearly on a daily basis throughout the pandemic, and the Liberal Leader would hold semi-daily press conferences but obviously in a crisis as big as the pandemic people want to know what the person in charge is saying because he’s ultimately the one with the decision making power at Queens Park.

The New Democrats didn’t make any gains on election night, but it was ultimately still enough to make NDP Leader Andrea Horwath announce her resignation on the night of the election. The NDP find themselves in quite a different situation from the Liberals because the NDP received thirty-one seats at Queens Park, still, enough for them to remain in the official opposition, and for Horwath to lead the opposition. Many people would argue she did the job of Opposition Leader very well, in being a critic of the Ford Government’s COVID-19 response and lending solutions in her press conferences that would follow any big decision from the Ford Government. The NDP is also in a different situation from the Liberals, primarily because they’ve already selected an Interim Leader. The party announced that they chose Toronto-Danforth MPP Peter Tabuns to serve as their leader on an interim basis. Tabuns has served in many roles in terms of Critics within the NDP caucus, he is well-respected by the NDP caucus and will likely serve as an effective NDP Interim Leader. The party will likely stay focused on having to unite the progressive portion of the party and the traditional labour faction of the party, something Horwath did quite well and something Tabuns has the ability to do well, too. They’ll want to focus on the issues, that Horwath focused on in her time as Leader of the party, issues such as Climate Change, Anti-Black racism, and they’ll likely continue to hold the Ford Government accountable for what they feel was an inadequate response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The voters of the riding of Guelph re-elected MPP and Party Leader Mike Schreiner. The party leader, Mike Schreiner has decided to stay on as Party Leader, after all, he’s the only re-elected MPP for the Green Party in the history of the party. It wasn’t all celebrations for party insiders and Green Party supporters on election night, however. The party was hoping to make gains in the Northern Ontario riding of Parry-Sound Muskoka. In that region of the province, the party ran a candidate who had been running for the Green Party since 2007, his name was Matt Richter, and the difference between Richter and the victorious PC Candidate Graydon Smith was only around five percent. The Green Party wants to be seen as a credible progressive opposition party at Queens Park, and well it’s true that Guelph MPP Mike Schreiner has punched above his weight, the party will still need to elect more MPPs if they want to be viewed as that credible alternative to those other progressive opposition parties at Queens Park in the legislature.

The PCs were of course the big story of election night, winning eighty-three seats, an even larger majority government than was won by the party in 2018. Of course, it is quite rare that the incumbent gets elected to a second consecutive majority government. The PCs will probably need to still reflect on some things, like how they will attract those audiences that they didn’t attract in this past election, but ultimately the party did what they needed to do in the election, in order for Doug Ford to be viewed as credible which was win a second term.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford and the Progressive Conservatives won the June 2 election in impressive fashion. They’ll form a second straight majority government after taking 83 of the 124 contested seats. That’s seven seats higher than they won in 2018, and a 16 seat increase from the dissolution of the previous legislative session.

The two main opposition parties, Andrea Horwath’s New Democrats and Steven Del Duca’s Liberals, earned 31 and 8 seats respectively. Both party leaders announced their resignations on election night. (The remaining two provincial seats were won by Green Party leader Mike Schreiner and Independent candidate Bobbi Ann Brady.)

With this victory, Ford established himself as one of Canada’s most important and influential Conservative politicians. This would have seemed like an impossibility several years ago.

Readers may recall the trials and tribulations involving Ford’s younger brother, Rob. A successful municipal politician, he was elected Mayor of Toronto in Oct. 2010. Alas, he had personal demons when it came to alcohol and drug use. Allegations of partying, lewd behaviour and smoking crack cocaine in one of his “drunken stupors” made local headlines. The story also went viral internationally thanks to frequent coverage by U.S. late night hosts like Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Kimmel and Jon Stewart.

Ford had been elected as a city councillor in Rob’s old stomping grounds, Ward 2 Etobicoke North, that year. He regularly defended his brother’s honour and reputation, and strongly pushed back against attacks from political opponents, critics and the media. They were part of a close-knit family. Wherever Rob Ford was, Doug Ford was close by.

When his brother, who had taken a leave of absence to deal with his substance abuse issues, was diagnosed with cancer in Sept. 2014, Ford ran for mayor in his stead and lost to John Tory. The former Toronto Mayor ran for city councillor, won his old seat back and passed away in Mar. 2016.

Some political observers understood why Ford had defended his younger brother on a near-daily basis. Many would have likely done the same thing if they had been in his shoes. The anti-Ford contingent, however, paid no heed to this and painted him with the same political brush.

When Ford unexpectedly abandoned his second mayoral campaign against Tory in Feb. 2018 to run for the Ontario PC leadership and won, his critics felt party members had made a poor decision and would live to regret it. When Ford won the general election on June 7, his critics pointed out the unpopularity of then-Liberal Premier Kathleen Wynne and said he simply rode an existing wave for political change.

When Ford, as Premier, reduced the number of Toronto’s council wards from 47 to 25, supported cuts to bloated municipal services, reduced several costly educational programs (including free tuition for low-income students), enforced back-to-work legislation to end the York University strike and faced some backlash with several patronage appointments, his critics questioned his every move and basic motives. When Ford announced short-lived COVID-19 restrictions related to police powers, school closures and keeping playgrounds open, his critics said his political goose was cooked and would only be a one-term Premier.

They were wrong in each and every instance. His political opponents didn’t – and, to this day, still don’t – understand the key to his political success.

The Premier, along with his late brother, had built a unique brand of conservatism. His guiding philosophy, Ford Nation, combines populist rhetoric and conservative principles. It stands for lower taxes, reducing government expansion and interference, fiscal prudence, supporting individual rights and freedoms, standing up for the little guy – and giving power back to the people.

Ford isn’t a traditional conservative ideologue, however. He’s always believed in building bridges with individuals and groups who aren’t necessarily natural allies. He successfully worked hand-in-hand with Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland during COVID-19, for instance. He earned the endorsement of several unions while promoting free markets and free enterprise. He provided strong leadership during the pandemic by developing strong ties with a medical community that was somewhat skeptical of working with him at first.

This is pure retail politics at its core. There’s something in his plan for just about everyone, and many Ontarians found a thing or two to call their own. They also learned this Premier is the genuine article. The man I met in his late father’s legislative office many years ago is the same man who is currently leading Ontario, and not the one who was trapped in the difficult, circus-like atmosphere of Toronto politics over a decade ago.

Ford has identified a political formula that could potentially work for Conservatives in Liberal Canada. With the federal cousins in the midst of a tense and somewhat volatile leadership race, he’s provided acknowledged frontrunner Pierre Poilievre and others with some important food for thought. We’ll see if they opt to consume any of it.

It’s also worth noting former U.S. President Donald Trump, former Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson employed similar political messaging and strategies to Ford’s during their election campaigns. These men are all different from one another, but realized their brands of conservatism needed to have broader appeal to achieve greater electoral success.

A subtle nod to the growing legacy of Ford Nation, perhaps.

Michael Taube, a long-time newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

Become a subscriber today!

Register