Former U.S. President Donald Trump beat Democratic Vice-President Kamala Harris in the Nov. 5 presidential election. He won the all-important electoral college by 312 to 226 votes, his biggest margin of victory in three elections. Trump will also win the popular vote for the first time, and likely end up a whisker above or below 50 percent.

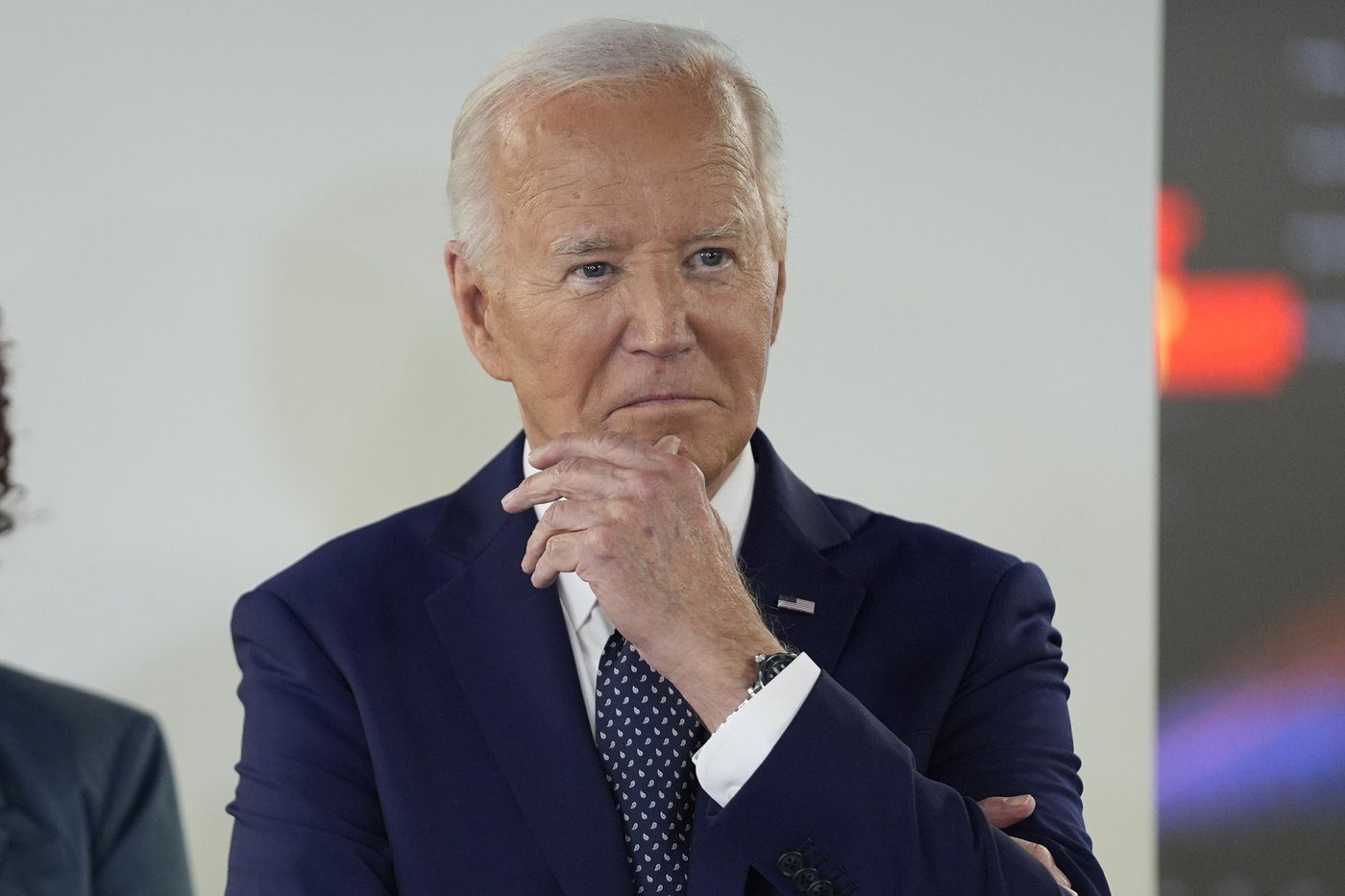

Several political commentators have suggested this year’s presidential election signalled the end of the era in U.S. politics. They claim it brought down the curtain on former President Barack Obama’s influence – and, in effect, current President Joe Biden, who served as Obama’s Vice-President. There’s certainly something to this analysis, although it’s probably too early to make this pronouncement.

One thing does seem clear. Trump’s victory is a powerful repudiation of the Democratic Party shifting way to the left.

James Carville, a longtime Democratic strategist, blasted his party for succumbing to “wokeism” – or, as he prefers to call it, “identitarianism.” He told New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd in a Nov. 9 interview that voters started to perceive “identity is more important than humanity.” He believes this was a fatal error in political judgment.

“We could never wash off the stench of it,” Carville said, specifically describing the strategy to “defund the police” as the “three stupidest words in the English language.” As he amusingly told Dowd, “it’s like when you get smoke on your clothes and you have to wash them again and again. Now people are running away from it like the devil runs away from holy water.”

There’s also Doug Schoen, another longtime Democratic strategist who regularly appears on Fox News. In a Nov. 6 op-ed for its website, he wrote that Trump’s election win was a “repudiation of the Democratic Party, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. There is no other way to see it. With over a 2 to 1 advantage in financial resources, the office of the vice presidency and the support of financial and political elites across the country, the fact that Donald Trump has won a convincing victory, in spite of a campaign that clearly got distracted in the last week, speaks volumes about the message the American electorate was sending in this election.”

Schoen provided some additional forward-thinking analysis. “Put another way, voters want a new economic policy that emphasizes smaller government, deregulation and lower taxes,” he suggested. “They want the wall completed and illegal immigration eliminated as much as possible. And they want the crime problem addressed fundamentally and systemically. The election results also suggest the limitations of the abortion issue as a motivating force. Put simply, the fact that the Democrats put virtually all their firepower behind the choice issue suggests the weakness of that appeal.”

This reminded me of Schoen’s 2007 book, The Power of the Vote: Electing Presidents, Overthrowing Dictators, and Promoting Democracy Around the World. A campaign consultant for over 40 years, he’s critiqued the Democratic Party’s leftward tilt for decades. Through the teachings of Daniel Patrick Moynihan, he came to understand that George McGovern lost the 1972 presidential race to Richard Nixon not due to “race hatred,” but rather because the former “had run a terrible general election campaign” and “abandoned the center.”

He was also concerned about the rise of left-wing populist politicians like Howard Dean. The Democrats had become vulnerable against the threat of the left, and the main support base was with liberal voters and little else. He was equally critical of Al Gore’s 2000 and John Kerry’s 2004 presidential campaigns, the latter of which he felt was a repudiation of the party by the voters for this leftward drift.

The Power of the Vote suggested a path to avoid defeat in 2008. “Democrats must face a hard truth: we do not have a natural majority coalition in American politics,” he wrote, and they must work hard to regain their old political coalition. He wanted to see a return to centrist Democratic positions with three mainstream political values: “opportunity (giving every American a chance to succeed), responsibility (the duties we owe to each other), and community (preserving and promoting families).”

Obama, as we know, won the 2008 election. He was a politician of the left, but masked his deficiencies by implementing Schoen’s language and values in his platform. It’s unclear whether this was an intentional strategy, or he and his team accurately read the political tea leaves. Either way, it helped him beat John McCain, a maverick Republican with moderate conservative policies.

Biden moved away from his more natural home in the political centre during his one term in office. His administration attempted to appease progressives and far-left activists at every turn. It weakened his public image, and his poor health and weakened state would have led him down the road to defeat against Trump had he stayed in the race.

Harris’s failed 2024 campaign was similar to McGovern’s failed 1972 campaign. Her deficiencies were far worse, however.

She was a “lousy candidate,” as I pointed out in a Nov. 8 National Post column, who was politically vapid and struggled mightily to explain her policies during tough and friendly interviews. Harris looked out of her element time and time again. Meanwhile, her campaign with Tim Walz “may very well be the most left-leaning ticket the Democrats have ever put forward in a presidential election,” as I noted in an Aug. 23 National Post column.“Harris’ political ideology is also more left-wing than Biden’s ever was on his worst day. She’s pro-abortion, pro-affirmative action, supportive of strict gun-control legislation, a defender of sanctuary cities, believer in restrictive environmental protection laws and one of 10 senators to oppose the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement because it didn’t tackle climate change. She’s a progressive’s progressive.”

Roger Kimball of The New Criterion went even further. He stated in an Oct. 25 Daily Telegraph op-ed that Harris was “the single worst candidate for president from any party in the history of the Republic.” It’s hard to argue with this astute assessment.

To quote an old proverb, “the more things change, the more they stay the same.” Case in point, the Democratic Party and its far-left tendencies. Senior leadership needs to listen to Carville, Schoen and others and shift back to the political centre. If not, they face the grim prospect of repeated defeats in future presidential elections.

Michael Taube, a long-time newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.