As the Iran-Israel war raged last month, I visited Bethlehem in the West Bank,

, to better understand how Palestinians coped with the conflict, which is now in a ceasefire. There, I spoke with several locals who, despite being deeply critical of Israel, called for regional peace and harboured little love for the Iranian regime. Perhaps the world would be a better place if more people — particularly anti-Israel activists in the West — listened to these voices.

While Bethlehem is normally only a 20-minute bus ride away from Jerusalem, Israeli security forces

at the beginning of the war with Iran. Checkpoints proliferated. Gates were closed. The city’s main entrance (heavy iron doors flanked by armed soldiers) was shut on the morning of my visit, as were most of the inbound roads. Yet, after several failures, my taxi eventually found an open entry.

In more peaceful times,

would come to Bethlehem each year, primarily to see the Church of the Nativity where Jesus Christ was born. But the October 7 massacre committed by Hamas in southern Israel, followed by the wars in Gaza and against Hezbollah,

decimated Israel’s tourism sector

, leaving the West Bank

. Many of the city’s districts were essentially empty — only thick quiet existed amid shuttered storefronts.

“Since the war against Gaza, the situation was horrible. We are isolated,” Jack Jackaman, a Christian Palestinian who owned a small woodworking shop near the church told me. He said that Israel’s stricter use of gates and checkpoints made it near-impossible for Palestinians to travel within the West Bank. These restrictions had, furthermore,

: lines of cars jammed the roads near gas stations, awaiting their rations.

“We are not secure. No income. The family completely without income. My workers — everybody is not safe. We have nothing. No secure future,” he said.

Although Jackaman blamed Israel for the war with Iran, he also believed that the Iranian regime is irrational and that neither Tehran nor

should have nuclear weapons. He was afraid of Iran’s missiles, because, even if they were aimed at Israeli cities, they still flew over the West Bank and could malfunction and

land on Palestinian communities

.

While Jackaman believed that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is a warmonger, he considered Judaism a “normal religion” that calls for “peace and love,” much like Christianity and Islam. “As Christians, we have to follow the teaching of our Jesus and to pray for peace and try not to make war. The war will not achieve peace,” he said.

Joseph Kaleel, an elderly Christian Palestinian woodworker, felt similarly: “We just keep praying for peace of Jerusalem. For everyone. For everybody. Doesn’t matter your religion, your race, your colour, your country. We want peace.” He had once employed half a dozen labourers at his workshop, but the tourism industry’s wartime collapse had forced him to lay them all off. He sold his tools just to survive. The basement that once housed them was derelict and coated in dust.

When the Iran war erupted, Kaleel ran to the grocery store to buy food for his children and oil for his car. He sat in front of the television for the first few days, sleeplessly watching Al Jazeera “from the morning till the morning,” and worried about errant Iranian missiles: “They don’t have eyes. They make mistakes.”

While Kaleel believed that the Iranian people are peaceful, he called their regime “very crazy” but “very strong.” He worried that hostilities could drag on, given that the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s had lasted for eight years.

When I told him that some Westerners

because they believe this furthers the Palestinian cause, he seemed irritated. “This is wrong. Brother, this is wrong,” he replied. He believed that Iran should abandon its militancy, not seek regional hegemony, and that this would stabilize the Middle East by neutralizing

in Yemen and Lebanon (the Houthis and Hezbollah).

Kaleel’s grandson Michael, who also worked in the family business, concurred with his grandfather: “We need peace. We don’t care about Iran and what they do.” Over a cup of mint tea, he described the unemployment and destitution that had befallen Bethlehem after October 7 which worsened amid the newest war. These troubles had left some locals, particularly orphans and widows, crushed “like the grass between two elephants fighting.”

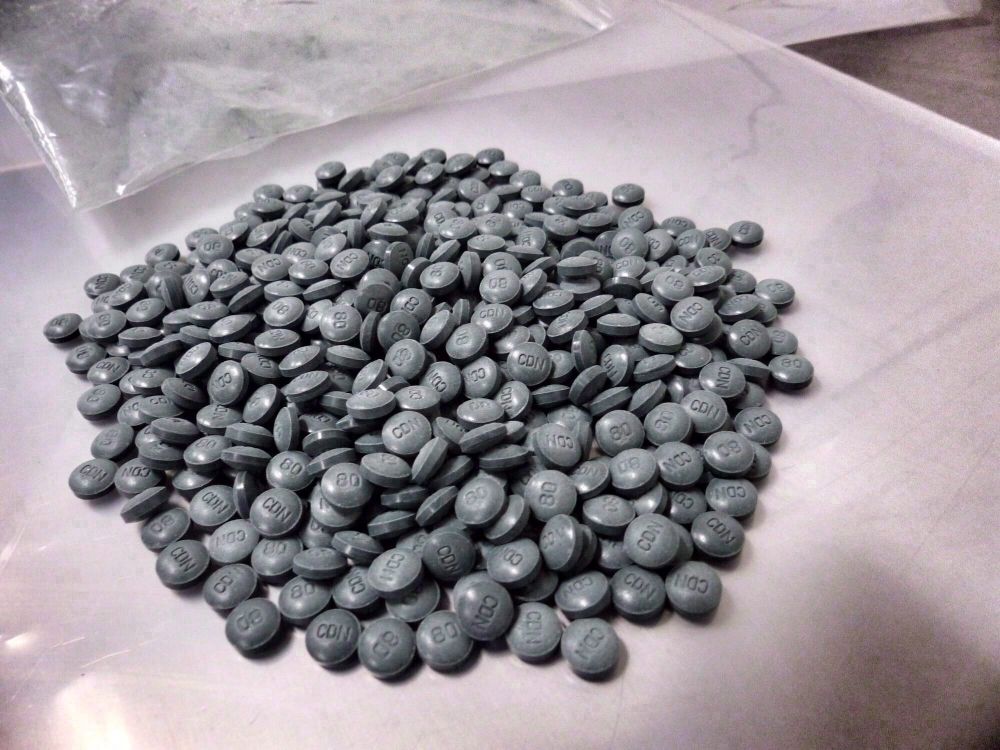

He said that an Iranian missile had

near his home, shaking its walls. Yet, like most Palestinians in the West Bank, he had no bomb shelter to retreat to, so all he could do was pray to God for safety. “You can’t say Palestinian and Iran are the same. We are never the same,” he firmly asserted, noting that Iran had supported the “bad” and “crazy” people behind October 7.

In

(which consists of run down low-rise apartments, not tents), I spoke with a Muslim vendor of ice cream and juice. He had once made a good income working in Israel, like many Palestinian labourers, but now, with the wars, that was no longer possible.

“All we ask for is to live in peace, raise our children, and live a dignified life. People have reached the point of despair. In mosques, the number of people begging is now greater than the number of people praying,” he said. “It’s a heartbreaking situation.” He, too, feared Iran’s rockets: “They don’t distinguish between civilians and soldiers. Palestinians or Israelis. In the end, everyone loses in war.”

Ahmed Al-Sabba, another street vendor, was similarly anxious. His children couldn’t sleep out of fear of Iran’s missiles, whose explosions sounded “terrifying,” so he would stay awake with them until the morning. “We do not support Iran, or the Iranian government, or sectarianism or wars.”

He said that, though Israel’s restrictions had made life much harder, he nonetheless wanted coexistence: “We see what is happening in Gaza, we don’t want to see it happen in the West Bank. Wars only grow bigger and destroy relationships. Our message is simple: we want to live in peace. We don’t want wars.”

The following week, after the Israel-Iran war abruptly ended, I visited a Palestinian peace activist in his village near Bethlehem (disclosure: I paid him to act as my guide and translator on the previous trip; his name has been withheld for his safety). Sitting in his living room, he explained that it is unproductive for Westerners to conflate Palestinian and Iranian interests, partially because each nation belongs to a different branch of Islam.

Iranians are predominantly Shias. Palestinians are predominantly Sunnis. Historically, there has been a great deal of violence between these two sects, so, according to the peace activist, some Palestinians fear that they could be Iran’s “next target” should it defeat and occupy Israel.

Nonetheless, many of his neighbours climbed onto their roofs to watch the Iranian attacks. Some were curious spectators. Others wanted to witness the destruction of Israel, despite their misgivings about Iran. And then there were the parents “who wanted to see if any missile was heading to their home so they could just collect their kids and say their final goodbyes.”

National Post