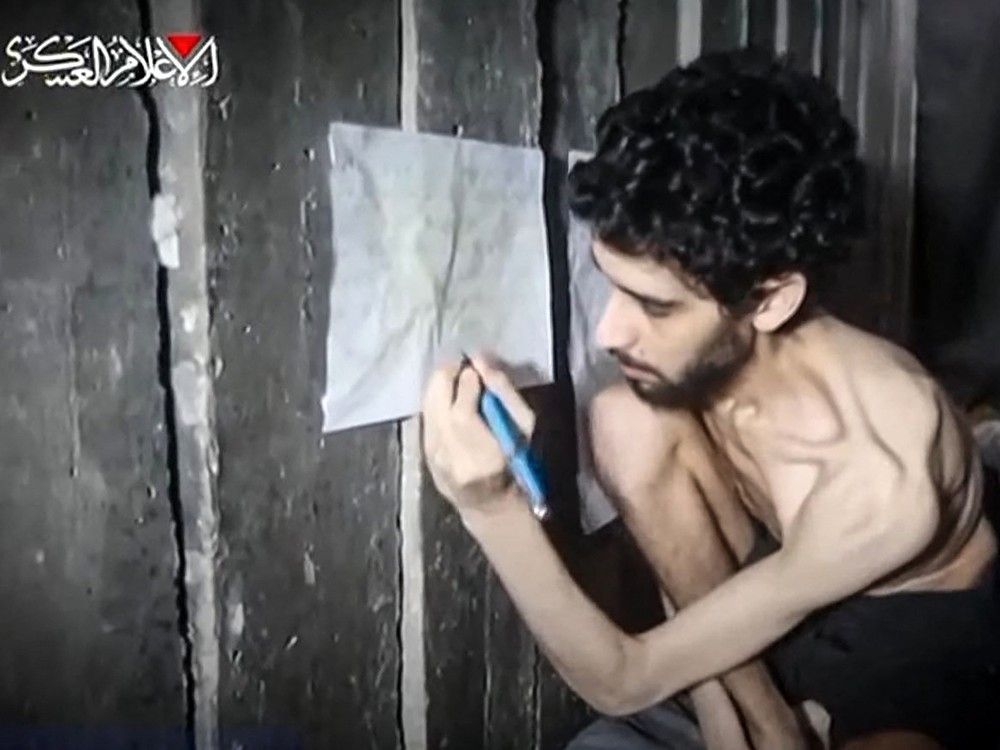

“The pictures take you back 80 years. But we were promised that those images of a living skeleton wouldn’t come back. The promise was: never again.”

So says a heartbroken Tamar Eshet, cousin of Hamas hostage Evyatar David, who was seen in a recent disturbing

being forced to dig his own grave in a narrow tunnel somewhere in Gaza.

In the video, David is pale, his body thin, bony, and wasted.

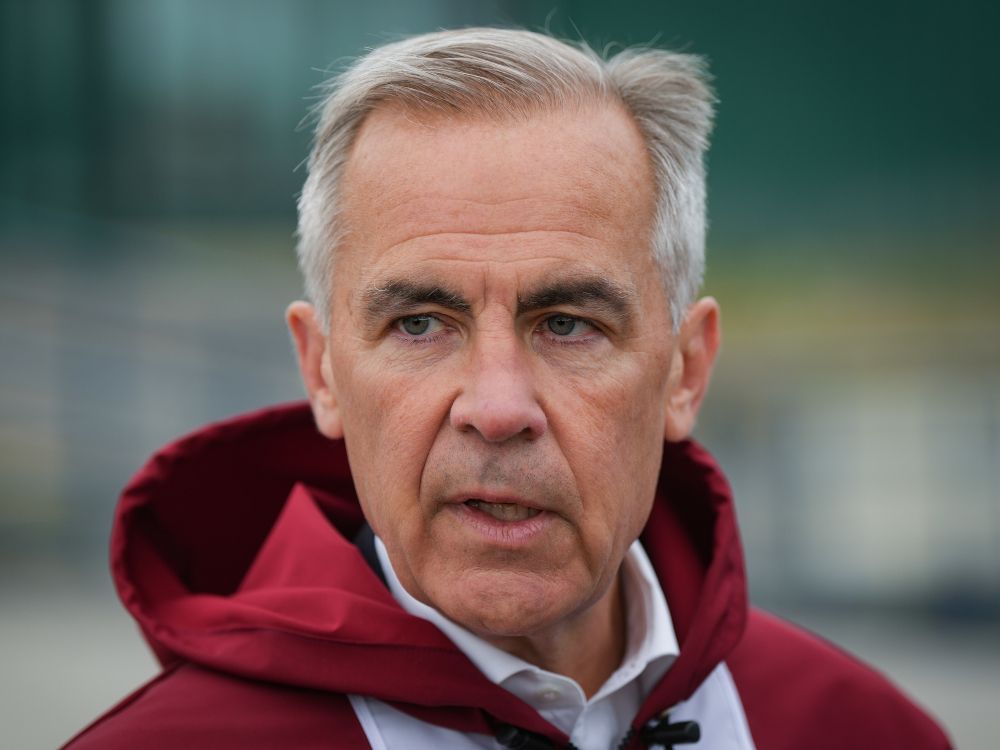

Hamas released the video only days after Prime Minister Mark Carney joined U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer and French President Emmanuel Macron in saying they would

a Palestinian state.

Likely emboldened by the announcements, the terrorists were happy to show the world how their depravity was starving the hostages to death. Hamas also said they would not disarm until a Palestinian state was established.

Far from pushing the path of peace forward, Carney and the others have succeeded only in giving succor to the terrorists.

National Post

interviewed Eshet, who believes Hamas saw what the three world leaders were doing and immediately reneged on a hostage deal.

“When you give (Hamas) power, when you give them a prize for their actions, then you are letting them starve the hostages because they say, ‘OK, we are going to get whatever we want anyway.’ Now the world can see the consequences of their actions, of their irresponsibility. (Hamas) took a step back from a hostage deal right now because of everything that happened and they feel like they can do anything. We are giving a prize to terror. Giving them power is justifying terror and the world has to think about what they are doing,” she said.

Evyatar David was 22 years old, a barista in a cafe, when he and his friends attended the Nova music festival that was attacked by terrorists on October 7, 2023.

David and his childhood friend, Guy Dalal, were among the 251 hostages taken by Hamas after the terrorists had butchered 1,200 people. Of those taken, 49 hostages are still in Gaza, but only about 20 are still believed to be alive.

“Evyatar was 22 when he was kidnapped. He was still thinking what to study, what does he want to do with his life” said Eshet.

However, his favourite thing in the world, she said, was playing guitar and he dreamed of becoming a music producer.

“He’s a really calm guy. He’s the advice giver to his friends, they would come to him,” she said. “And we live next to each other. Our houses are close. We are a close family, and ever since October 7, we are even closer.”

As the slaughter began at the festival, David was hiding with friends in some bushes.

“Two of his friends were murdered in a bush right next to him. He was kidnapped with one of his best friends, Guy Dalal. They know each other from kindergarten, and they’re still being held together,” said Eshet.

Well, relatives believe they are being held together, but Hamas isn’t the kind of organization that gives regular updates on its hostages.

In February, the anguished families of David and Dalal watched another Hamas propaganda video showing the two men.

Hamas

David and Dalal sitting in a van, watching a hostage handover ceremony. But the tantalizing glimpse of freedom was all that the men got. After the ceremony, they were taken back to Gaza and the tunnels where they are being imprisoned.

“We hope that they are still together,” said Eshet.

Then last weekend, Hamas released a new video, this one showing a wretched, emaciated, and clearly starving David. In the video, David marks what looks like a handmade calendar and indicates days when he has eaten and days when he has not. At another point, he is seen digging a hole and says it is to be his own grave.

But if Hamas is trying to convince the world that all of Gaza is starving, the families of the hostages are not convinced.

Eshet says that in the video an arm, presumably of a terrorist, can be seen handing a can of lentils to David. She notes that it is the arm of someone who has been well fed.

Hamas is deliberately starving the hostages, she says, but the terrorists are not going hungry.

“Hamas isn’t “an organization that fights for the Palestinian people. They don’t care about them. They starve them just as much as much as they starve Evyatar. They take away the food, they steal the food from their own people,” Eshet said.

The cruelty in the video was too much for David’s mother.

“His mother hasn’t watched the latest videos because she thinks she would break down if she sees that. She can’t see her son in this condition and she knows she has to be strong and keep on fighting for him and be strong for her other children,” said Eshet, noting that David has an older brother and a younger sister.

“It’s hard. We see the abuse, the torture, the starvation, and how cynically they do that. They use him for a video to show how they starved him. They were proud of it. They wanted to show the world how they’re starving Evyatar. And it breaks my heart to see him fighting to even talk. We can see that he’s using every breath he has to talk. It’s scary because in this condition we really don’t know how much longer he can survive.”

Eshet said she was shocked when she saw the video.

“I didn’t know what I was going to see. I froze. I was shaking and crying, and I didn’t know what to do. You feel so useless and helpless. As a Jewish person, as a person who has family who’s been in concentration camps, to see Evyatar like this, I don’t think there’s a word to describe the feeling: it’s horror, it’s pain.”

Seeing the video of David is a ghastly reminder for his family of the Holocaust and the haunting pictures of starving prisoners in the concentration camps. “Our family is here only because we escaped from the Holocaust,” said Eshet. “A lot of our great-grandparents were in concentration camps and in war camps and only my great-grandmother who came to Israel was the one who survived and had a family.

“We were promised that those pictures would never be seen again. This is the time for the world to say never again, and to make sure it doesn’t happen and to stop it.”

Eshet said the world must unite in bringing the hostages home. “We have to bring all the hostages back home. The world has to speak up, and stop giving Hamas more power and giving prizes for their actions, because that’s what’s been done in the last couple of weeks.”

David and the other hostages may not have much time left, she said. “They may have days or weeks in these conditions. The world must pressure Hamas to first give the hostages decent care, give them food and water and medicine and we know that they have this. That should be the first thing and then to get them back home. But time is not on our side.”

Eshet knows that ending the war and defeating Hamas is no simple thing. “Defeating Hamas is about defeating an idea, an ideology, and it’s much bigger than just the military aspect. It’s more complicated than that. This is all part of a campaign and the world is falling for it right now, they’re giving prizes to (Hamas) for starving Evyatar and for starving their own population. They (the politicians) need to have a responsibility when they do such things. We can’t praise terror. We have to be on the good side of history,” she said.

“I’m not an authority on how to end the war, but I think a hostage deal is the only hope” she said. “And I think it has to be as soon as possible because we’ve just seen that time is critical.”

National Post