This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

According to an Abacus Data poll taken April 28–May 3, 2023, “2 in 3 Canadians would vote to eliminate the monarchy in Canada.”

This tracks nicely with an Angus Reid poll taken a year before on April 5-7, 2022. It suggested that 67% of Canadians would oppose “Prince Charles as King and Canada’s official head of state.”

Canadians are nonetheless still in the early stages of talking about just what it would mean to leave the monarchy that resides in the United Kingdom.

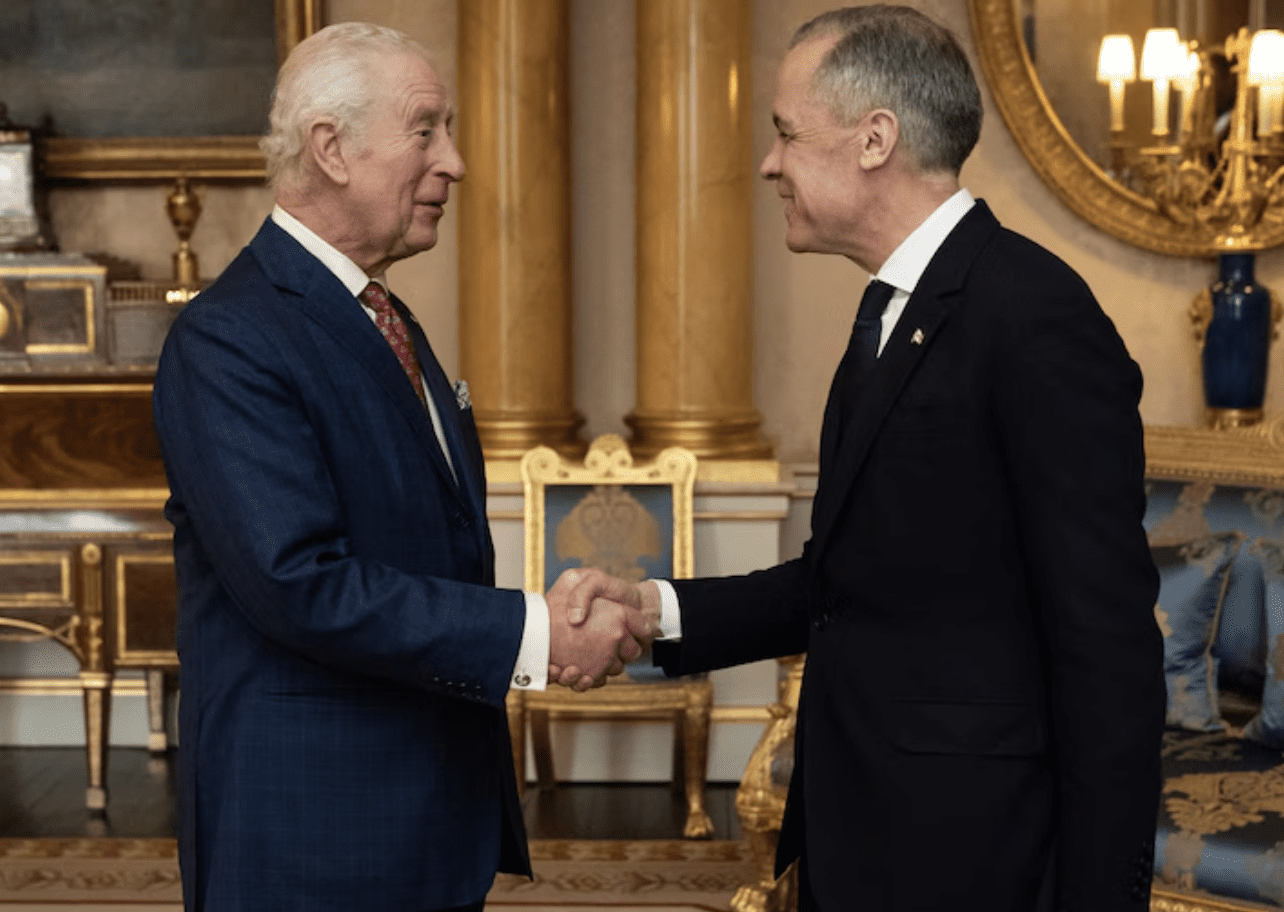

And now that King Charles III has been properly crowned, we at least ought to start talking about alternatives to the monarchy that make sense for Canadian institutions.

To take one glaring case in point, some recent polls ask about “cutting ties with the monarchy and having the prime minister become both the head of the government and the head of state, replacing the Governor General who is the representative of the Canadian monarch.”

Yet in the Preamble to what we now call the Constitution Act, 1867 Canada has “a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.” And one distinguishing feature of this kind of “Westminster” constitution is a ceremonial head of state above the ordinary partisan political struggle, separate from the head of government.

Having the prime minister become both the head of government and the head of state is to effectively try to Americanize Canada’s Westminster constitution, in a way that raises too many questions about just how government would work under the new order.

The only fellow former self-governing British dominion to try to leave the monarchy in this way is South Africa. And it seems fair to suggest that the consensus is this has not worked well.

More durable transitions to Westminster parliamentary democratic republics have taken place in Ireland and India.

The strategy here has been not to replace the Governor General, but to turn the office into an independent ceremonial head of state, that plays effectively the same role “above politics” as the monarch in Canada’s “Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.”

Ireland and India offer two different options for selecting the new democratized governor general or ceremonial head of state — paralleled, for example, by Iceland and Germany as similar parliamentary democracies formally outside the Westminster tradition. And these options have worked well since 1938 (Ireland), 1944 (Iceland), 1949 (Germany), and 1950 (India).

In Ireland the democratized ceremonial head of state is directly elected by the people of Ireland for a seven-year term.

Any Irish citizen over the age of 35 can seek nomination as a candidate. But a candidate must be nominated by at least 20 members of the Irish parliament or no less than four county councils. And this takes any extreme populist edge off the popular election principle.

In India the democratized ceremonial head of state is indirectly elected for a five-year term by an electoral college composed of the elected members of the federal parliament and the elected members of the state (and territorial) legislative assemblies.

Iceland is a parliamentary democracy outside the Westminster tradition, with a ceremonial head of state selected by direct election as in Ireland. Germany is a similar parliamentary democracy with a ceremonial head of state selected indirectly by federal and state legislatures, as in India.

In all of Ireland, Iceland, Germany, and India the new democratized ceremonial head of state is called a president.

There are reasons, however, for wondering whether this would ultimately make sense in Canada. And most of them involve the prospect of confusion with the quite different kind of president in the United States next door, who is both head of government and head of state.

Similarly, one attraction of leaving the monarchy by following the Westminster parliamentary democratic rather than the Washington presidential model, is that very little in Canada’s current federal and provincial governments has to change.

The Governor General (as even a democratized version of the ceremonial office might continue to be called) just takes over the role of the monarch. (Or more exactly the reformed Governor General would be Canada’s head of state in theory, as well as the head of state in practice the Governor General already is now.)

If we’re going to keep talking about leaving the monarchy (and no doubt we are : look at the polls), we ought to be talking about alternatives that follow Canada’s traditions of parliamentary democracy since the middle of the 19th century.

Trying to “Americanize” our current Westminster-style democracy that has served us well for more than 150 years is not a realistic option for the Canadian future.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

Become a subscriber today!

Register

Late last September 2022 the Vancouver pundit J.J. McCullough, who writes a sometimes controversial “Global Opinions” column for the Washington Post, published a perceptive piece headlined “In Canada, interest in the monarchy remains mostly an elite thing.”

All by itself this headline might be one answer to the headline on a late February 2023 Globe and Mail column by the ardent proponent of the Canadian Crown John Fraser: “Canada should show more enthusiasm for King Charles’s coronation.”

In fact most recent polling on the monarchy does suggest that a bare but growing majority of Canadians wants to politely wave goodbye to the institution.

In an Ipsos poll from last September, just after Queen Elizabeth II’s sudden death, 54% agreed “that now that Queen Elizabeth II’s reign has ended, Canada should end its formal ties to the British monarchy.”

A Pollara poll also from last September found only 35% “want Canada to remain a constitutional monarchy with the King as its head of state.” An Angus Reid poll from last April 2022 found only 26% answering Yes to “Do you think Canada should continue as a constitutional monarchy for generations to come?”

A Leger poll from last September found “only about a quarter of all respondents said they had been even moderately personally impacted by the Queen’s death.” Nearly 75% “said they felt little to no impact at all.”

Christian Bourque at Leger noted:“It got me thinking over the past four days, there’s nothing else on the news media than Elizabeth … Yet the majority of viewers don’t really care.”

There are some subtleties between the lines of these recent polls — especially in a real world where constitutionally waving goodbye to the British monarch requires the approval of Canada’s federal parliament and all 10 provincial legislatures.

To start with, there is understandably more support in Quebec than in the rest of Canada for ending the country’s now very vague ties to Buckingham Palace.

The Angus Reid poll from last April 2022 found that, Canada-wide, 51% answered a bold No to “Do you think Canada should continue as a constitutional monarchy for generations to come?” But this varied provincially from a low of 40% in Manitoba to a high of 71% in Quebec.

Even outside Quebec, however, the share saying No to the British monarchy was larger everywhere than the share saying Yes. And the share saying Yes was broadly comparable to the share saying Not Sure. In Alberta 45% said No, 30% said Not Sure, and only 25% said Yes.

It is true enough that there is as yet no overwhelming popular consensus (only a bare majority) saying No in Canada at large. Pro-monarchy elites seem to be taking comfort from the lack of “Freedom-Convoy” protests against King Charles III on Parliament Hill.

In the recent past both the Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star have published editorials broadly urging that the monarchy under the Constitution Act, 1867 isn’t broken and doesn’t need fixing.

John Fraser’s Globe and Mail plea that “Canada should show more enthusiasm for King Charles’s coronation” is coming from the same line of traditional tribal wisdom.

Yet the key problem with this plea is not just that a bare Canada-wide majority of voters already wants to wave goodbye to the monarchy. It is that only a quarter to at best one-third of the democratic electorate now seriously believes in the future of the institution.

In the end any dispassionate reading of recent polling evidence would arguably advise any Canadian government to restrain its enthusiasm for the coronation of Charles III. That just shows respect for what the Constitution Act, 1982 calls Canada’s “free and democratic society” today.

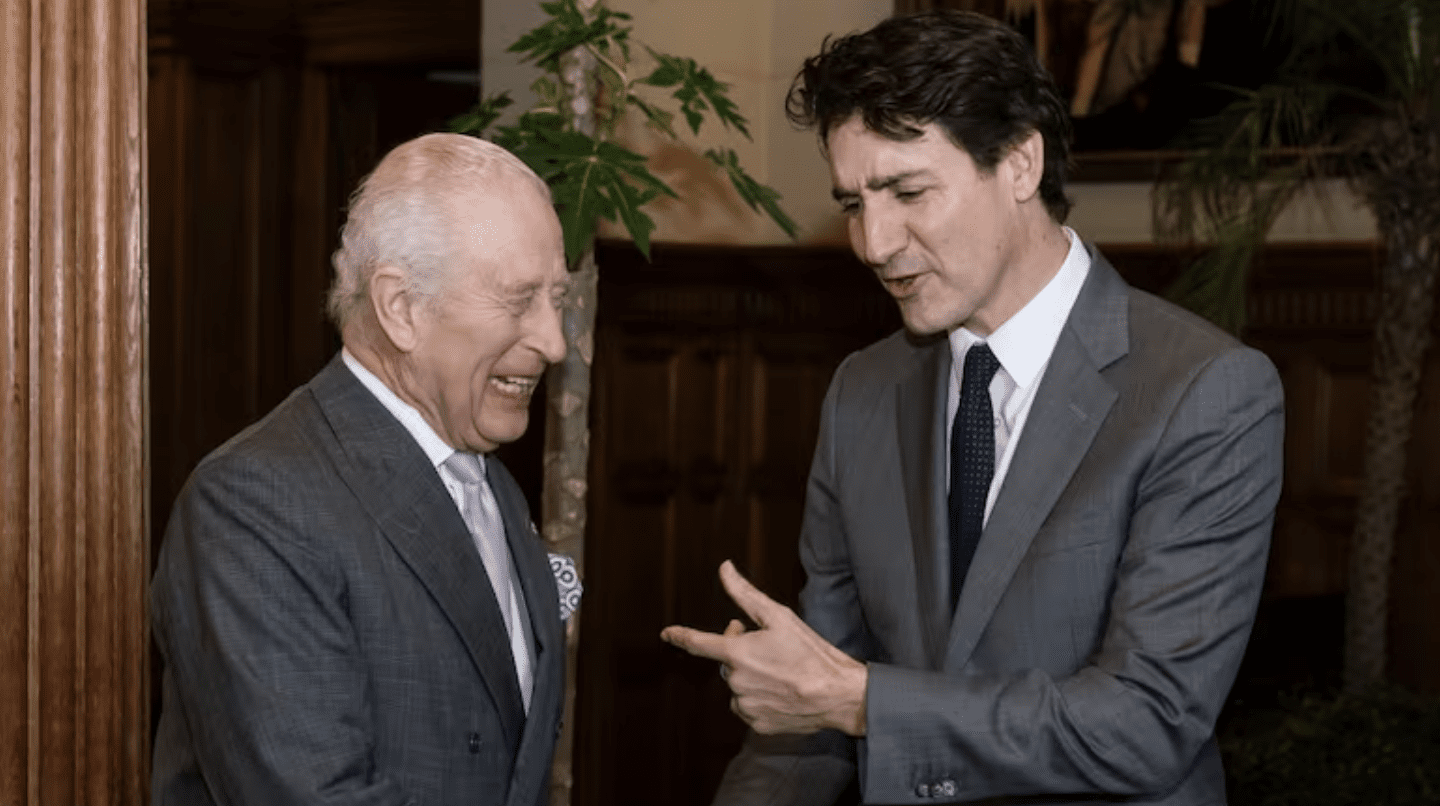

John Fraser also suspects that the Liberal government in Ottawa right now quietly agrees with the current bare majority that wants to politely wave goodbye to the British monarchy in Canada.

And, he suggests, if that is the reason for the “seeming inactivity surrounding our responses to the coronation, then the government should have the courage of its convictions and start a dialogue to turn Canada into a republic.”

Yet recent polling evidence might also arguably advise that the time for government to start such a dialogue in Canada is not quite here yet.

And this does seem the current policy of the Justin Trudeau Liberals. (Unlike Anthony Albanese’s Labor government in Australia, already in the words of the Sydney Morning Herald “undertaking a national consultation tour to shape a future campaign to cut ties with the monarchy.”)

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

Become a subscriber today!

Register

The government of Quebec has still not yet “signed” the Constitution Act, 1982, with its Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the “free and democratic society” of Canada today.

It sometimes seems almost possible, however, that without Quebec’s struggles to find itself in the unravelling British empire after the Second World War, the rest of the country may never have bothered with this crucial piece of modern Canadian constitutional law.

It is similarly not often noted that Quebec has a greater share of its population reporting “Canadian ethnic or cultural origins” than any other province. History of this sort may also be worth remembering in assessing the now adopted Bill 4 of François Legault’s re-elected government of Quebec.

The bill’s purpose is to make the Oath of Allegiance to the new King Charles III optional for members of Quebec’s National Assembly. And this is warmly supported by all parties.

Yet not everyone outside Quebec sees the point of Bill 4. A few weeks ago an editorial in the Globe and Mail bemoaned “The empty fight over a symbolic oath in Quebec.”

Elected officials, the Globe and Mail argued, ought to “take a basic Canadian civics course.” As urged in a 2014 Ontario Court of Appeal decision, in swearing an oath to the British monarch an individual is just swearing allegiance to “a symbol of our form of government in Canada.”

The trouble here is that this only makes sense if you are a monarchist. And as Quebec’s Democratic Institutions minister Jean-François Roberge urged as he tabled Bill 4 : “We’re democrats. We’re not monarchists.”

Opinion polls have been suggesting for a while now that a growing majority of Canadians, from coast to coast to coast, would agree with M. Roberge.

Meanwhile, as The Canadian Press has explained : “Constitutional scholars are divided” over whether the Quebec National Assembly has “the power to unilaterally eliminate the oath requirement” in the province.

The Legault government can at least reasonably argue it does have this power under section 45 of the Constitution Act, 1982 — which prescribes that, with a few exceptions, “the legislature of each province may exclusively make laws amending the constitution of the province.”

In any case Democratic Institutions minister Jean-François Roberge “doesn’t expect pushback from Ottawa or legal challenges to the bill.”

According to The Washington Post, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau himself has already observed that “these oaths are governed by the Assembly and Parliament themselves,” and the “National Assembly has the right to decide how they want to organize their swearing-in process.”

If Quebec can finally make its lawmakers’ oath to the British monarch optional, without serious challenge in the courts, that could eventually prove of interest to other provinces.

Both BC and Alberta, for instance, might have New Democratic provincial governments by the summer of 2023. They could find it helpful to emulate Quebec’s use of section 45 to end the old monarchist oath.

More generally, the requirement for Canadian federal and provincial lawmakers to swear allegiance to the British monarch is in what we now call the Constitution Act, 1867. And this was originally an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom known as the British North America Act, 1867 — finally “patriated” by Canada via the Constitution Act, 1982.

This 1867 Act is written in an archaic ceremonial language of the old British empire, where words do not always mean exactly what they seem to mean. The Governor General, for example, is assigned responsibilities that are in fact performed by the Prime Minister, who is nowhere even mentioned in the Act.

In such a universe who knows just what “the Oath of Allegiance contained in the Fifth Schedule to this Act” in section 128 of the Constitution Act, 1867 may eventually come to mean?

Meanwhile again, changing the oath of allegiance to the monarch that new Canadian citizens must also still swear does not involve any form of constitutional amendment. It only requires an ordinary act of the federal parliament.

Put another way, there is no requirement for a Canadian citizenship oath to the monarch in the Constitution Act, 1867 because there was no such thing as a Canadian citizen until 1947. This was when the first Citizenship Act passed by the Parliament of Canada took effect, in the immediate wake of the Second World War. (Until 1947 — and since 1763 — residents of Canada were just “British subjects” in the empire “on which the sun never set.”)

The “free and democratic society” alluded to at the start of the Constitution Act, 1982 continues to evolve in Canada today. And, Quebec is still providing an oversized share of the constructive political energy behind this Canadian evolution.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

Become a subscriber today!

Register

The Queen’s funeral is just behind us. It is still too early for any deep debate on the long journey ahead to a Canadian republic.

The Globe and Mail editorial board has nonetheless already opined that “Canada is stuck with the monarchy. We should thank our lucky stars for that.”

Some who for excellent patriotic, democratic, multicultural, and even economic reasons altogether disagree with this sentiment may already have their own thoughts.

Those who share the Globe and Mail’s opinion, for instance, often profess scepticism about related opinion polls. Canadian politicians themselves have so far largely ignored the growing evidence of Canadian “republicanism” or “anti-monarchism” in the polls of the past few decades.

Yet very soon after the Queen’s unhappy death our federal and provincial leaders were proclaiming Charles III the new King of Canada. And as this happened some voters may have remembered two recent surveys by the Vancouver-based Angus Reid Institute.

Both polls suggested that a two-thirds majority of Canadians (66%-67%) “oppose recognizing … Prince Charles as King and Canada’s official head of state.”

Polls on the monarchy in Canada can depend a lot on the exact questions asked. A very recent Leger poll taken just after the Queen’s death asked whether respondents “thought the accession of King Charles to the throne was good or bad news.” In this case 15% said good, 16% said bad, and 61% were “indifferent.”

The Leger and two Angus Reid polls do point in similar broad directions for Canada. Leger found that a three-quarters majority (77%) “felt no attachment to the British monarchy.”

Another very recent poll from Pollara Strategic Insights reported that: “Only one third of Canadians believe the country should remain a constitutional monarchy.”

The second Angus Reid poll, published April 21, 2022, was headlined “The Queen at 96: Canadians support growing monarchy abolition movement, would pursue after Elizabeth II dies.”

The Leger poll points this way as well. But its questions also elicit a parallel note of apathy on the issue, which has its own history and logic.

Early reactions to Queen Elizabeth II’s unhappy passing were similarly nuanced. The online blogTO in Toronto reported that “People think Canada should … become a republic.”

The left-wing rabble.ca concluded: “Fully abolishing the monarchy would be a tall order and would require amending Canada’s Constitution, getting the provinces on board, and likely settling other Constitution issues, such as the status of Quebec.”

Whatever else, none of this means that the Canadian people are “stuck with the monarchy.”

Getting the legislatures of all 10 provinces on board will be challenging, especially when it almost certainly means settling a few other nagging constitutional issues at the same time.

In the end, however, such things must finally depend on what the great majority of the Canadian people want. That is a key part of the “free and democratic society” noted at the start of the Constitution Act, 1982, which finally “patriated” Canada’s Constitution from the United Kingdom.

Growing popular support for an end to the monarchy in Canada in the new age of King Charles III could ultimately be the driving force behind an at last successful cut at the still haunting constitutional issues that eluded the failed Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords 30 years ago.

And this could help build a stronger Canada for the global storms ahead.

On closer examination, abolishing the monarchy in a parliamentary democracy like we have in Canada today, while politically awkward in several respects, is not difficult in principle or unprecedented in practice. It has already been pioneered by our fellow former British dominions in Ireland and India.

Very quickly, there is an important enough practical role for a head of state (monarch) separate from the head of government (prime minister) in our kind of parliamentary democracy.

But in Canada this role is now played by the governor general — in theory a representative of the British monarch, but in practice a Canadian appointed by the Canadian prime minister since the early 1950s.

All we have to do to politely wave goodbye to the monarchy is change our official head of state from the British monarch to the Canadian governor general (under whatever new name and selection method … or not??).

It will take a long journey to politically dot all the “i”s and cross all the “t”s in even such a common-sense process. But if this is what the great majority of the Canadian people who vote in elections finally want (in our less indifferent moments), it is not a difficult thing to do.

And if we are even half as democratic as we like to imagine, our free and democratic society in the Constitution Act, 1982 is almost certainly bound to finally arrive at a Canadian republic, even at some point not too much further down the road.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.