The federal election has been a busy time for anyone involved in politics, media and column writing. With the readers’ permission, I decided to have a little fun and do something different.

I used to enjoy delving into the world of creative writing. Did it a fair bit when I was in grade school and high school. In many ways, it served as an early training ground for what I currently do today.

A few weeks ago, I happened to come across an old column I wrote back in 2019. A couple of editors read it, appeared to enjoy it – but were never able to publish it. I’ve always regretted that it never saw the light of day. So, I decided to change this. I went through the original version, souped it up a bit et voilà.

May I present A Tale of Two Prime Ministers.

********************************************************

Charles Dickens’s classic novel, A Tale of Two Cities (1859). is set in London and Paris during the French Revolution. His book perfectly encapsulates this intriguing and difficult period in world history.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” the author wrote in the opening paragraph. “[I]t was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

Let’s fast forward to 2025. The curtain opens for A Tale of Two Prime Ministers, a Dickensian-like story involving Jean Chretien and Stephen Harper. The revelation of their long-standing friendship surprised the general public, but not to those who already knew in private. Both men are situated in Canada, and wanted to express their views on the “best of times” and “worst of times” in U.S. President Donald Trump’s America. They see a nation where concepts such as wisdom, foolishness, incredulity, good and evil are typically associated with the eye of the beholder.

The Liberal Chretien, who was Canada’s 20th prime minister (1993-2003), had a hot-and-cold relationship with the U.S. He kept Canada out of the war in Iraq, and there were periods of anti-Americanism in his party caucus related to then-President George W. Bush’s leadership that he allowed to run its course.

Chretien expressed some frustration with the U.S during Trump’s first term. In his book, My Stories, My Times, the former PM described Trump as “fanatical” and believed Americans made a “monumental error” when they elected him in 2016. (He probably feels the same way today.)

“I fear that Hillary [Clinton]’s defeat, and the arrival of the fanatical Trump, mark the true end of the American Empire,” Chretien wrote in one chapter. “You can understand why Aline and I are so happy to have the Clintons as friends, and almost as proud to be removed as far as possible from the unspeakable Donald Trump.”

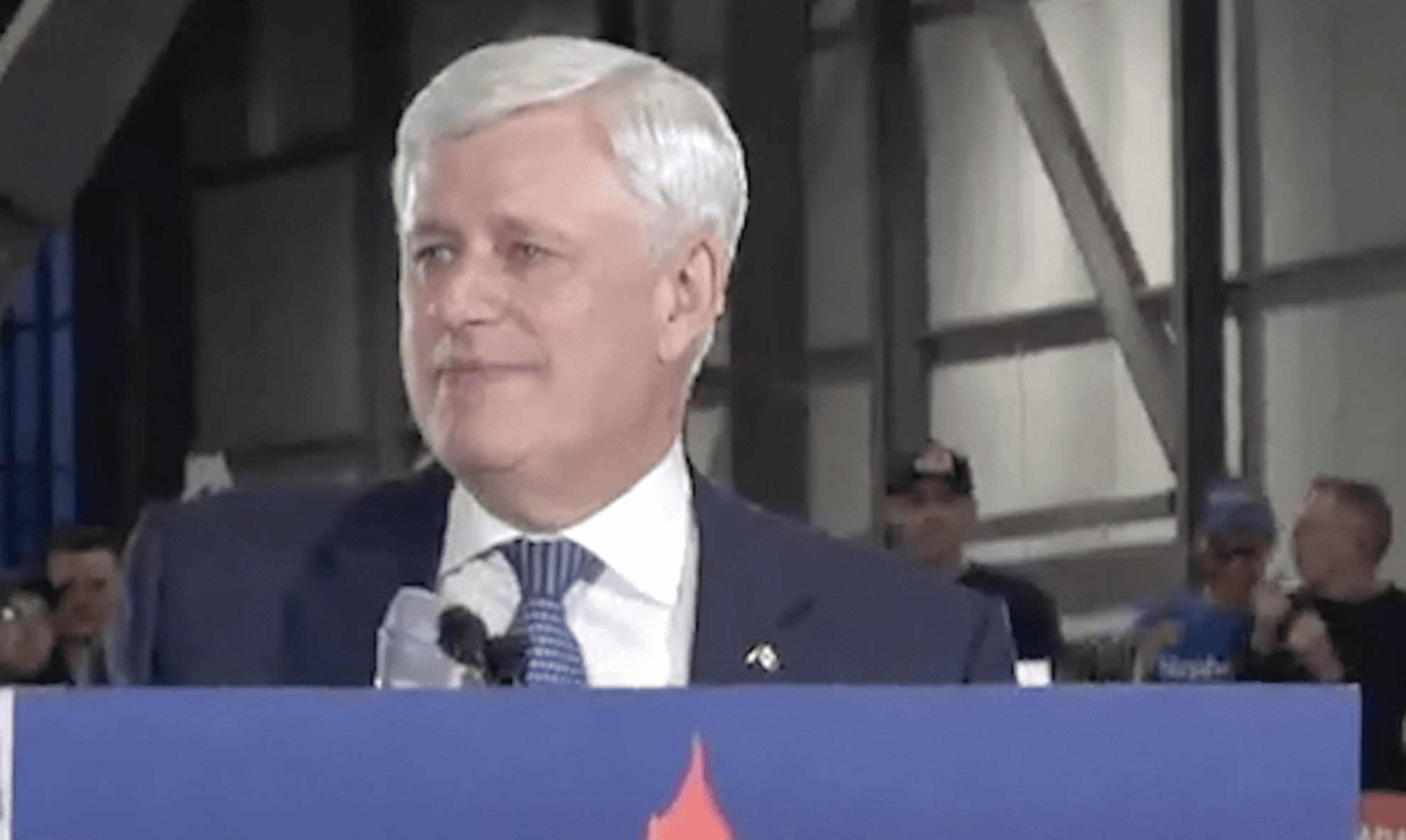

The Conservative Harper, who was Canada’s 22nd prime minister (2006-2015), had a much friendlier relationship with former Presidents Bush and Barack Obama. He observed Trump and the U.S. rather differently than his Liberal counterpart.

Harper’s book, Right Here, Right Now: Politics and Leadership in the Age of Disruption, looked at the role of conservatism and populism in the U.S. and around the world. The starting point was Trump. He had “not impressed” Harper during the GOP presidential primaries and, like others, believed it was “obvious that Trump was not really a conservative and not even a Republican.” The would-be president’s stunning victory forced the author to reevaluate the political situation. He concluded that a “large proportion of Americans, including many American conservatives, voted for Trump because they are really not doing very well…in part, because of some of the policies we conservatives have advocated,” such as globalization.

Harper’s view was to “stop obsessing about the flaws of Trump and the Brexiteers,” and for conservatives to start using certain components of “present-day populism,” which led to the former’s electoral achievements, to their political advantage. Whether Trump was a successful or unsuccessful President, the former PM believed “the issues that gave rise to his candidacy are not going away.” In particular, he advocated for conservatives to rally behind “reformed democratic capitalism,” with renewed working-class opportunity and greater community cohesion” in today’s globalist-populist age. My guess is that he holds similar sentiments during Trump’s second presidential term.

Chretien and Harper obviously had (and still have) very different political ideologies and personal world views. They examined Trump’s presidency through unique political lenses. Which of their tales seemed more logical and realistic to support in this hyper-partisan political era?

Chretien touted a typical left-leaning sentiment about Trump: I don’t like him, I hate talking about him, and he’s destroying his country. He’s therefore following some of the negative sentiments Dickens described in his book: foolishness, incredulity, Darkness, despair and evil.

In contrast, Harper touted a uniquely right-leaning sentiment about Trump: I don’t agree with him, I recognize he’s figured out something about politics and society that others missed, and I believe it would be wise for conservatives to incorporate these concepts. He’s therefore following some of the positive sentiments Dickens described in his book: wisdom, belief, Light, hope and good.

Hence, the latter tale that Harper unveiled made more sense. Present-day populism and reformed democratic capitalism may not have long-lasting appeal with the modern electorate, but it seemed to be a wiser strategy in dealing with Trumpian-style politics than Chretien’s fire-and-brimstone approach.

One wonders if the conclusion of A Tale of Two Prime Ministers will ring similar to Carton’s unspoken final thoughts in A Tale of Two Cities, “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.” All will be revealed in time, good ladies and gentlemen.

Fin.

Michael Taube, a longtime newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.