“I didn’t want to kill anybody,” Eric Nagler says. “And I was afraid if I did go in that, because I was a pacifist, I’d get sent to the front lines and shot. So anyway, I dodged the draft.”

Nagler, who is now 83, grew up in Brooklyn, New York, in the 1940s. Like millions of young American men, he was draft-age when U.S. ground troops first set foot in Vietnam in 1965. “My brother came home from university one day and said that he was a conscientious objector and explained what that was,” Nagler says. “I thought it was a terrific idea.

“I claimed conscientious objection, and I had a student deferment, and we went back and forth like that … Finally, the notice came for me to appear at Whitehall Street on a particular day, and instead I drove across the Vermont border into Canada.”

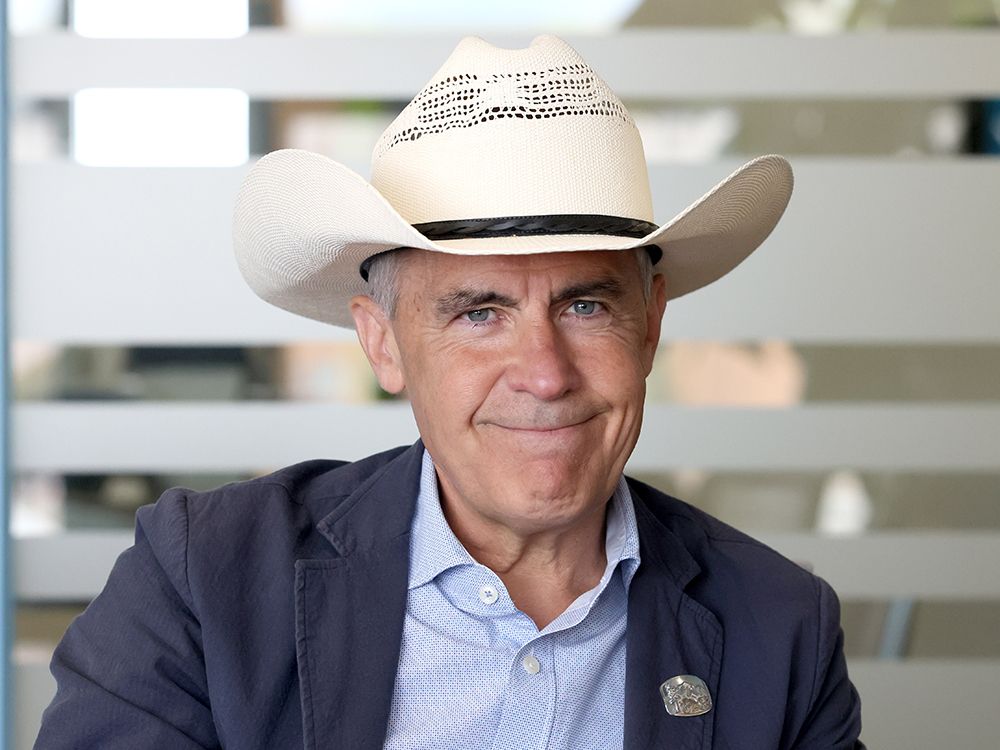

After settling down in Toronto, Nagler opened a music store and went on to become a beloved children’s television personality on

The Elephant Show

and Eric’s World. He’s written three books for children and released countless songs, with titles ranging from You Got a Place Where You Belong to Sneezes. From time to time, he even plays the sewerphone — a saxophone-shaped instrument made of plumbing pipes.

Nagler isn’t bashful about his choice to leave the United States. “Down there in the States, we were called draft resisters, but it was fine up here just to be a draft dodger,” he recalls. “We’re not very good at war, up here in Canada.”

Over 50,000 Americans came to Canada in opposition to the Vietnam War, based on estimates from John Hagan’s book, Northwest Passage (2001). This was the largest exodus of political migrants from the U.S. since The American Revolution. Some hoped to avoid the draft, others deserted after months or years of service, still others left for ideological reasons. Though they weren’t subject to the draft, Hagan writes that more women migrated than men, “most as partners and spouses, and some on their own.”

An elaborate vocabulary emerged in the 1970s to categorize these American newcomers: they were dodgers, evaders, deserters, resisters, émigrés, exiles or plain-old immigrants. Each term came with its own baggage. “Deserter” carried a sense of national betrayal; “resister” had a more sympathetic ring to it.

These categories concealed the messier and more personal realities of coming to Canada. The National Post spoke to nine U.S. war resisters about their journeys north. Their lives had no unifying narrative. Many were highly educated and went on to make lasting contributions to Canadian politics and industry. Some were musicians, painters and authors who immersed themselves in the growing counterculture of the 1960s — be it in the Yorkville neighbourhood of Toronto or in the mountain towns of British Columbia. The war resisters changed Canada and Canada changed them.

As Canada grows estranged from our neighbours to the south, an age-old question comes back into focus: What sets us apart? Prime Minister Mark Carney says it is our ability to

recall the names of the two puppets

on CBC children’s television show Mr. Dressup. Pierre Poilievre, in a strangely American twist, says it is the

“protective arms of a solid border”

and the promise that “hard work gets you a great life.”

Jeff Douglas

, in his renowned rant from a 2000 Molson Canadian beer ad, says it is our belief that “a toque is a hat” and “a chesterfield is a couch.”

The resisters of the Vietnam era had better answers. Maybe it takes years of living between countries to see the gap fully. Or maybe there was something about that era — a time of national reckoning for both countries — that made our differences easier to discern. Decades later, their stories offer some clarity on Canada’s place in an ever-tumultuous continent.

Eric Nagler is the first to reassure Canadians searching for a sense of national difference. “The United States government is run by a bunch of big-time criminals, and that’s more true now than it ever has been,” he says.

“In Canada, it’s run by small-time criminals. You know, you can get along here.”

How the war began

In 1945, Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam’s

independence from France

. His speech began with a quote from the U.S. Declaration of Independence. “All men are created equal,” he proclaimed. “They are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.”

France reimposed colonial rule less than a month after Ho’s address, beginning a brutal conflict known as the First Indochina War. President Harry Truman, worried about the spread of communism in Indochina, committed vast amounts of American money and arms to the French military. By the middle of 1954, the United States was paying about 80 per cent of French war costs. And so the conflict became, as many Vietnamese still refer to it,

“the American war.”

In the 1950s and early 1960s, U.S. leaders tried to conceal their interest in Indochina. Nancy, a resident of the B.C. Interior and the daughter of a U.S. air force officer, lived in Arizona at the time. “There was a little box in the daily news, and it told you how many American advisers there were in Vietnam,” she recalls. (Nancy wanted to use only her first name to speak more openly.) “Those numbers grew, day after day after day, and then pretty soon the numbers started to not make sense.” By the end of 1964, around 23,000 American advisers were stationed in Vietnam.

Nancy wasn’t the only one to question why South Vietnam needed so much advice. Newspapers, activists and concerned citizens began to interrogate the ballooning U.S. presence in Vietnam as the costs of war grew higher. Graham Greene’s

The Quiet American

(1955) satirized America’s failing efforts to fly under the radar. Alden Pyle, a fictional economic adviser from America, is murdered in Vietnam, and his family receives a cable stating that he died a soldier’s death. “The Economic Aid Mission doesn’t sound like the Army,” Graham’s narrator remarks dryly. “Do you get Purple Hearts?”

Soon enough, the war came out of the shadows. In March 1965, the first U.S. troops landed in Vietnam; by 1969, there were more than 500,000 of them. Mark Atwood Lawrence, a history professor at the University of Texas, notes that public support for the war was initially high. Many young Americans rallied around the flag, driven in part by cultural memories of the Second World War.

Yet support faded as the conflict dragged on and “more body bags came back, with no apparent end in sight,” explained Lawrence in an interview with the Post. Then U.S. president Lyndon Johnson failed to provide a clear rationale for the conflict, and Lawrence says that the public “had a really hard time seeing how American interests were really at stake in a fight so far away from American shores.”

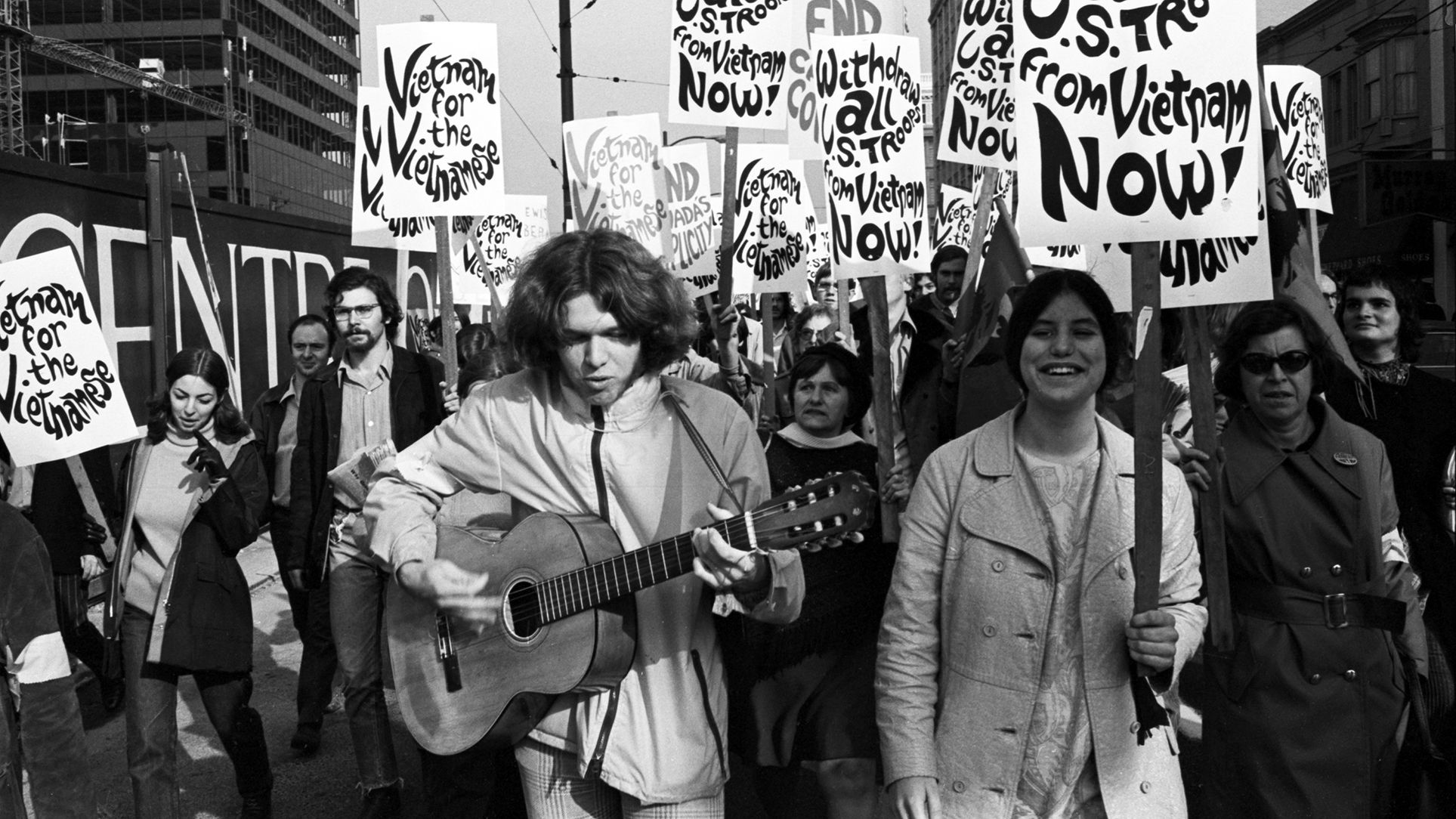

Americans took to the streets to express their discontent. About 35,000 rioters

attacked the Pentagon in 1967

, climbing walls and throwing rocks and vegetables at military officers. The

Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam

— a 1969 demonstration of over 500,000 people — was one of the largest antiwar protests in U.S. history.

Corky Evans, a resident of the B.C. Interior, recalls attending several protests while growing up in California. “I saw the police breaking people’s heads and blood everywhere and hundreds of cops,” says Evans. “My younger brother went to prison that day for the crime of stopping to throw up as people were being beaten up in front of him.”

The antiwar movement was part of a larger wave of political upheaval in the U.S.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of 196

2 led thousands of Americans to convert their basements into nuclear fallout shelters. The 1965 Civil Rights Act banned racial segregation in public spaces, sparking violent backlash against African-Americans.

Medgar Evers

was assassinated in June 1963, then John F. Kennedy in November 1963, then Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968.

“It was just all falling apart,” Evans recalls. He eventually migrated to British Columbia in 1969 out of opposition to the war.

Between country and conscience

“Sarge, I’m only 18, I got a ruptured spleen, and I always carry a purse,” sang

Phil Ochs

. “I’ve got eyes like a bat and my feet are flat, and my asthma’s getting worse.”

The Draft Dodger Rag was released on Ochs’ 1965 album I Ain’t Marching Anymore, and was later covered by Pete Seeger, Tom Paxton and John Denver. The song takes on the persona of a “typical American boy” who faces his local draft board. Ochs satirizes the vast and creative set of excuses that American youth used to evade the draft, from allergies to epilepsy to working at a defence plant.

The song was popular because it spoke to a newly surfacing truth: a lot of American boys weren’t going to Vietnam. Students could defer conscription for years at a time, as could some married men. Draftees could also gain medical exemptions if they had a letter from their private doctor, notes Christian Appy, history professor and author of Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers in Vietnam (1993). Well-informed draftees found ways to feign colour blindness, mental illness, homosexuality and so on. “There were actually people who paid to have braces put on to get an exemption,” Appy says in an interview with the Post.

The wealthier the family, the more likely their sons were to benefit from exemptions and deferrals. According to Appy’s Working-Class War, about 80 per cent of Americans who served during the Vietnam War were from working- or lower-class households.

To assuage cries of class discrimination, newly elected president Richard Nixon introduced

the lottery draft in 1969

. Each day of the year was written on a piece of paper and placed inside a plastic capsule. The capsules were randomly drawn out of a jar on live television. If the first day chosen was July 19, then each draft-eligible man born on that day would have Lottery No. 1. The draftees were then called for service in order of their lottery number. It was a “bingo-style system for choosing which 20-year-olds were going to be sent away to die for commercial and political agendas,” recalls Fred Rosenberg, a U.S.-born resident of Nelson, B.C.

Draft calls grew higher when the war expanded and Nixon abolished both occupational draft deferments and deferments for fathers. As evading the draft legally grew more challenging, thousands of young men began eyeing the northern border.

Draft dodgers faced criticism from all directions. A hawkish political right viewed them as traitors to their country. Many of the dodgers’ own parents had served in the Second World War and valued military service as a national tradition. Genevieve, a resident of Nelson, B.C., is the daughter of a Vietnam-era draft dodger. When her father dodged the draft, his parents contacted the FBI and asked for their son to be tracked down.

Even among vocal antiwar activists, draft dodgers were often shunned for taking the perceived easy way out. Students for a Democratic Society, one of the largest antiwar groups in the U.S., urged Canadians to stop supporting Toronto’s draft counselling centres. When Joan Baez performed at a 1969 concert in Toronto, she urged the draft dodgers to return home. “What (the draft dodgers) are doing is opting out of the struggle at home,” she declared. “That’s where they should go, if only to fill the jails.”

These criticisms were tinted by the growing understanding of draft evasion as a class privilege. “These people from the elite don’t go (to Vietnam),” said Richard Nixon in a taped conversation about draft dodgers. “They’re all f-cking running (to Canada) … I don’t buy that repression issue.”

Jack Todd, a deserter from Western Nebraska, spoke to this class dynamic more gently. The draft dodgers “had gone to University of Wisconsin or Berkeley or something,” he said. “They came up with their VW Beetle and their girlfriend or wife, and they already had a job lined up and all that.”

It’s true that the dodgers were disproportionately from college-educated households, according to Frank Kusch’s book All American Boys (2001). It was often at university that men heard about the possibility of migrating north. And, in 1967, Canada introduced a points-based immigration system, which gave priority to migrants with more education, work experience and connections.

Yet the image of the draft dodger conjured by the American public — of a rich, long-haired Ivy League graduate fleeing to downtown Toronto in cowardly avoidance of his national duties — isn’t quite right. For one thing, they weren’t all rich. Many upper-class men were able to gain exemptions earlier in the process, rendering a move to Canada unnecessary.

While knowledge of Canada was limited early in the war, migration became easier after the publication of Mark Satin’s

Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants

in 1968. The manual instructed dodgers on how to rack up enough points to get across the border, how to avoid criminal punishment and how to find housing in major Canadian cities. (“Most Canadians do not live in caves or igloos,” the manual advises.) It sold almost 100,000 copies.

Satin also personally counselled hundreds of draft dodgers in Toronto. “We got huge numbers of middle-class and lower middle-class kids who were very idealistic,” he recalled in a recent interview with the Post. “They didn’t really have options.”

For another thing, the dodgers’ opposition to the war extended beyond a personal unwillingness to fight. “There’s been a real tendency over the years to hang a lot of importance on the draft,” notes Mark Lawrence, the professor from the University of Texas. “I think sometimes that’s a way of dismissing the movement. I wouldn’t say, of course, that it was never a factor, but it’s probably been exaggerated to some extent as a motivator for antiwar activism.”

Even for those who did flee out of personal fear, it’s hard to see their decision as a cowardly one. The draftees’ options were to go overseas for two years to fight in a war they considered destructive and futile, commit identity theft and go underground or end up in federal prison. Conscription presented an impossible choice between country and conscience.

Life in Resisterville

On Halloween of 1969, Corky Evans and his wife ended up in a hospital in Duncan, B.C. “It was midnight, and her water had broken. So we had to go to the hospital to have this baby, but we had no money and we didn’t have a doctor.”

They drove to the hospital and left their two other children in the car parked outside. Evans’ wife was admitted to the maternity ward. “I went and stood at the front door waiting for somebody to come and ask me for money,” Evans remembers. “Because that’s how I had learned the health system works where I had grown up. I’m standing there in the dark. It’s now 1 in the morning or something.”

A nurse came by to ask Evans what he was doing. “My wife is upstairs having a baby, and I’m standing here waiting to talk to somebody about how I’m going to pay,” said Evans. The nurse told him to go upstairs and take care of his wife, and that they would talk about payment the next day.

“I just stood there in the dark. I started to cry. I had never had such an experience in my life where somebody in the health-care system cared more about the well-being of the people than the money.”

Evans migrated from California to Vancouver Island, where he worked as a longshoreman. After a brief stint in the Northwest Territories, his family settled down in the West Kootenays of British Columbia. He would go on to become an MLA for the Nelson-Creston district and hold several cabinet positions in the provincial NDP.

By the late 1960s, the Kootenays had become a hub for the draft dodgers. Many arrived in Vancouver before travelling to the B.C. Interior, where land was cheap and a vibrant counterculture was emerging. The Doukhobors, a Russian religious minority exiled in the early 20th century, helped provide the migrants with housing and jobs. The epicentre of American migration was Nelson, B.C., a small community tucked beside the West Arm of Kootenay Lake. The town became known as “Resisterville.”

The draft dodgers changed Nelson. Professor Kathleen Rodgers, author of

Welcome to Resisterville

(2014), writes that the influx of war resisters was akin to “dropping the population of a large university campus into a remote rural community.” The dodgers took on key roles in local anti-logging protests, made Nelson a nuclear-free zone and, decades later, protested the Iraq War. Many started or led communes — Harmony’s Gate, the Reds and the Blues, and the New Family. One war resister, Jeff Mock, began running a local tofu business.

Of course, Nelson changed the draft dodgers, too. While many dodgers moved to the B.C. Interior with a back-to-the-land aesthetic, they generally came from large cities and lacked the skills to maintain crops or build homes. The residents of Nelson helped the migrants adjust to a rural lifestyle; they wrote books and started community organizations to teach farming and construction.

Other dodgers embarked on spiritual journeys. Nancy and her husband migrated to B.C. after receiving a draft letter in the mail. They travelled through the province, visiting an ashram and eventually joining the New Family commune. Nancy didn’t cede herself fully to the counterculture. “I was a mother at that point, so I wasn’t going to go winging off in the crazy land,” she says. “But I was interested in the spiritual stuff a lot … I taught myself how to meditate, and then, you know, I became part of that world.”

An extremely forgettable city

“Toronto itself is in many ways an extremely forgettable city, sprawled out on the flat north shore of the lake, with endless ticky-tacky suburbs unrelieved by scenery or imagination,” wrote Canadian historian Douglas Myers in a contribution to Satin’s Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants. Myers assures readers that Toronto is nevertheless “a city of many small important pleasures — quiet tree-lined neighbourhoods, clean streets, good schools.”

By the late 1960s, Toronto had become a mecca for Americans on the lam. While some dodgers enjoyed the remoteness of the B.C. Interior, others were ambitious young professionals who preferred an urban setting.

Toronto was an especially appealing choice because the government of Vancouver — the other large, English-speaking city in Canada — had grown openly hostile to war resisters. “I don’t like draft dodgers,” declared Vancouver mayor Thomas Campbell in 1970, “and I will do anything within the law to get rid of them.” He proposed that the 1914 War Measures Act (which allowed the Canadian government to suspend civil liberties in wartime) be used against “any revolutionary, whether he’s a U.S. draft dodger or a hippie.”

Several organizations cropped up to assist American migrants in Toronto with housing, legal aid and social support. The largest group was the Toronto Anti-Draft Programme (TADP), founded in 1966 by the Student Union for Peace Action (SUPA) at the University of Toronto. They resettled hundreds of dodgers in Baldwin Village, Yorkville, the Annex and other neighbourhoods surrounding the university.

“Within a few months, I had a list of literally 200 Torontonians who were housing (the draft dodgers),” recalls Mark Satin, a key organizer in the TADP. “People were constantly calling the office asking if they could help.” Not all of them were stereotypical leftists who opposed the war, Satin notes. “Many of them were simply people who had empathy for the situation.”

The draft dodgers integrated quickly into the free-spirited, eclectic youth culture of 1960s Toronto. “A popular pastime in Toronto is visiting Yorkville Village to spot the beatniks, oddballs, and Bohemia,” said CBC reporter Larry Bondi

in a 1965 broadcast

. “But now the name of the game for visitors is to spot the American draft dodger.”

Some resisters remained highly engaged with the antiwar movement while living in Canada. Jack Colhoun grew up in a patriotic family in Upstate New York. He deserted the U.S. army, where he had served as a second lieutenant, and moved to Toronto for roughly a decade.

“We didn’t want to forget the war, and we didn’t want the American people to forget the war,” Colhoun says. He became an editor for Amex Canada, a magazine for American war resisters in Canada. Amex sought to publicize the stories of Americans fleeing the war, and worked closely with antiwar veterans’ organizations.

Other resisters kept a deliberate distance from wartime politics. Bob Griesel migrated in 1969 from Tacoma, Wash., to Edmonton. He wasn’t selected for military service, but left the U.S. after seeing the war’s effects on his draft-age peers.

“My friends who I went to high school and college with who’d been drafted were starting to return from their tours of duty,” Griesel recalled in a recent interview. “We caused them to be mentally disfigured and physically disfigured and many of them ruined for life. A couple of them I knew ended up dying from leukemia due to Agent Orange. And my question was, ‘Why did we do that to those young men, for that purpose, at that time? What was the point?’”

Griesel chose to integrate fully into Canadian life, putting memories of the war behind him and avoiding American TV channels. The people of Edmonton “didn’t give a darn where I came from,” he says. “Nobody up there was talking about the war.”

The Last Resort

“There was this marvellous house,” recalls Mark Satin. “It was huge. It was painted army green, ironically enough, and there were two guys sitting in front who looked kind of weird.”

It was autumn of 1968, and that army green house was in the middle of Vancouver, a few blocks from False Creek. Satin, a recently migrated resister from Texas, signed the lease for $75 a month. He and his friends converted the house into a hostel for war resisters from the U.S., and called it “The Last Resort.”

Satin estimates that somewhere between one-third and one-half of the men at The Last Resort were deserters. While dodgers left before joining the military, deserters were people who had served for some time before parting ways. “Many of (the deserters) were in terrible emotional shape,” Satin remembers. “When they came here, some of them were virtually silent. Some of them just sort of mumbled.”

For seven months, Satin cooked, cleaned and washed bed sheets for The Last Resort’s guests. He served dinner every night at 6:30 p.m. — spaghetti three nights a week, chicken livers with rice or beef Stroganoff on the other days. “I knew that they needed structure, whether they were middle-class or working-class or deserters,” he said. On Sunday nights, they would have open houses where Vancouverites could buy dinner for 50 cents and meet the resisters.

Running The Last Resort was gruelling work. Satin personally counselled each migrant, and estimates the hostel served over 1,000 people altogether. Many struggled to adjust. One deserter, after being accidentally woken up, “immediately leaped up in his karate crouch, ready to kill the person who’d woken him.” Another became dependent on hard drugs and had to be forcibly removed.

A few months in, Satin left the hostel unsupervised for a weekend while visiting a friend. He returned to find the house’s inhabitants huddled in blankets by an unlit stove, eating Wonder Bread. “It was kind of funny, but it was horrible, too,” Satin says. “These were 18-, 19-year-olds who really didn’t know how to cope.”

According to Hagan’s Northwest Passage, there were more than 432,000 desertions during the Vietnam War, fewer than one per cent of which happened on the battlefield. No written law in Canada discriminated against deserters, and Hagan notes that Canada had taken in many war resisters from Hungary and Czechoslovakia before the war in Vietnam.

Yet in 1966, Canada’s immigration department covertly instructed officers to deny admission to all deserters. The U.S. wasn’t pressuring Canada to turn the deserters back — at least officially — but Hagan suspects the Canadian government worried about future retaliation.

It didn’t help that almost 70 per cent of Canada’s immigration officers were military veterans, based on a report cited in Hagan’s Northwest Passage. Many veterans believed deserters were shirking their obligations and looked for ways to deny them entry. Points-based immigration, implemented in 1967, attempted to standardize admissions; still, the points rubric was extremely vague, giving officers significant discretion over who was kept out.

This de facto exclusion of deserters became clearer to the public over time. In February 1969, five undergraduates from York University pretended to be American deserters and tried to enter Southern Ontario from the United States. Four out of five were denied entry before even filling out an application.

Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government faced mounting pressure to admit deserters more freely — from antiwar groups and the United Church of Canada, but also from Canadians wary of American control. “Since when is it a function of the Canadian government to enforce U.S. laws respecting the draft?” wrote one Canadian in a letter to Allan MacEachen, the immigration minister at the time.

In May 1969, the federal government announced that draft dodgers and deserters would be admitted to Canada without consideration of their military status. Whether someone was a draft dodger was “an irrelevant question,” Trudeau declared in a

U.S. news conference.

“We also know that a number — perhaps a superior number — of Canadians come to the United States to join the U.S. Army,” he noted with his signature half-smile, “and there may be some solace in that.” By Hagan’s account, the number of male, draft-age landed immigrants from the U.S. tripled in the five months between April and August 1969.

Deserters faced a unique set of challenges in Canada. While dodgers tended to be college-educated, most deserters were lower- and working-class Americans who had been forced to serve because they lacked the information, connections or wealth needed to evade the draft. When they moved north, they were less likely to have friends or family to rely on, and their lack of formal education made it hard to find work.

“Living in exile wasn’t easy,” says Jack Colhoun, a military deserter who came to Canada in June 1970. “I learned in August of 1970 that my mother had cancer … My mom was my only living relative. We had to go through her struggles with cancer and eventual death. I couldn’t even go to her funeral without risking being arrested and put in jail.”

President Jimmy Carter

pardoned the dodgers in 1977

, but he didn’t pardon the deserters. Many were unable to return home for fear of military prosecution, even decades after the war. As recently as 2006, a British Columbia resident who had deserted the U.S. Marines in 1968 was arrested and held in an American military jail when he tried to visit Nevada for vacation (he was ultimately discharged after a week-long detention).

Perhaps most significantly, deserters often bore permanent physical or psychological injuries from the war. Alice, a woman from the Kootenays, recalled her husband’s decision to leave the U.S. in the early 1970s. He had served in Vietnam as a medic and helicopter repairman in 1969 and witnessed graphic acts of violence.

After returning to a disintegrating America and being told he had one more year to serve, Alice’s husband fled to Canada. “He had some desperate experiences (in Vietnam),” Alice says, “and just retreated into this place where he could no longer handle confrontation of any kind. He felt he had no other choice but to leave.” Alice’s real name has been changed to protect her family’s privacy.

Vietnam in retrospect

What leads someone to see a war differently? Often, it’s a trickling stream of information — news headlines, television footage, protests on a nearby lawn. But many resisters also describe turning points in their understanding of the war — moments where the conflict suddenly became sharper and more personal.

For Jack Todd, the turning point was a conversation with his childhood best friend, who had returned home from a helicopter base in Vietnam. “I went down to his house one night … (he) had seen some really horrific action, and he had pictures of GIs holding a string of Viet Cong ears that they had cut off and things like that.

“That was the pivotal thing that gave me nightmares,” Todd says. “I just couldn’t get it out of my mind.” He moved to Vancouver and then to Montreal.

The Vietnam War itself was a turning point for America — the thing that would give the nation nightmares for decades to come. The draft dodgers were raised in the glow of the Second World War, amid unprecedented American wealth and dominance. They allowed themselves to imagine a radically equal America. By the time the draft letters came in the mail, both a coveted past and an imagined future were fraying at the edges. The trust, pride and idealism of postwar America were never fully restored.

Less acknowledged is the possibility that the war transformed Canada, as well. The draft dodgers left an enduring imprint on Canadian culture. Todd became an influential sports columnist at the Montreal Gazette, where he’s worked for 39 years. Eric Nagler brought the sewerphone, Jesse Winchester brought the guitar, William Gibson brought the cyberpunk. The dodgers also brought with them a distinctly American form of politics: a propensity for standing on lawns with garish signs and speaking loudly about injustice.

In a larger sense, Vietnam marked Canada’s tentative separation from the foreign policy objectives of our southern neighbour. We had followed America obediently through the Second World War, then the formation of NATO, then the Korean War. Trudeau’s welcoming of American exiles was one of the first Canadian decisions since the Great Depression to openly defy U.S. interests.

It’s easy to find parallels between Vietnam-era politics and our current predicament — an increasingly authoritarian America, a newly defiant Canada, a flock of migrants heading north. Yet many of the war resisters argued that North America is experiencing something new.

Some feel that the current state of American democracy is incomparable to past lapses. “This isn’t just a changed political climate,” says Bob Griesel, who moved back to Washington State in the ’70s to be with his family after spending 17 years in Canada. “This is an absolute coup and revolution. I can’t compare it to anywhere we’ve been.”

Others say that conscription made politics more personal than it is today. “There was no apathy,” says Nancy, who migrated to British Columbia during the war. “You were either on one side or the other side. I walked in peace marches, and the people on the sidewalk would jeer at you and call you names and spit at you.”

Conscription gave the war an immediate, inescapable significance for a generation of draft-age men — and for their girlfriends, wives, parents, siblings, teachers. For most North Americans today, the wars in Ukraine, Gaza and Syria live at a comfortable distance. No matter how much moral outrage we feel, we can always choose to look away.

Most striking was the sense of personal and cultural freedom that many interviewees experienced in Canada. The war resisters lived through an incredibly turbulent decade. At the age of 18 or 19, they became strangers in a strange land. Yet almost all of them spoke about the Long Sixties with a vivid nostalgia.

“I would go off and rent a room here for $9, rent a room there for $12,” says Mark Satin, recalling the years he spent in Toronto in the ’70s. “There wasn’t AIDS. There wasn’t herpes. You could find a girlfriend just by talking to someone in a park or in a grocery store.” He sighs. “By the Summer of Love and the late ’60s, we were talking to each other in ways that I’m not sure your generation does.”

About half of the war resisters remained in Canada permanently. Some have stayed politically vocal over the years, advocating on behalf of the few hundred American deserters who fled to Canada during the Iraq War to avoid military prosecution. But most eventually faded into the woodwork, embracing a new way of life and allowing time to erode their old national ties.

Fifty years after the end of the Vietnam War, the resisters have few regrets.

“It took me a long time to reach this point,” says Jack Todd, “but I’m really proud that I did it. I think it’s the defining act of my life.”