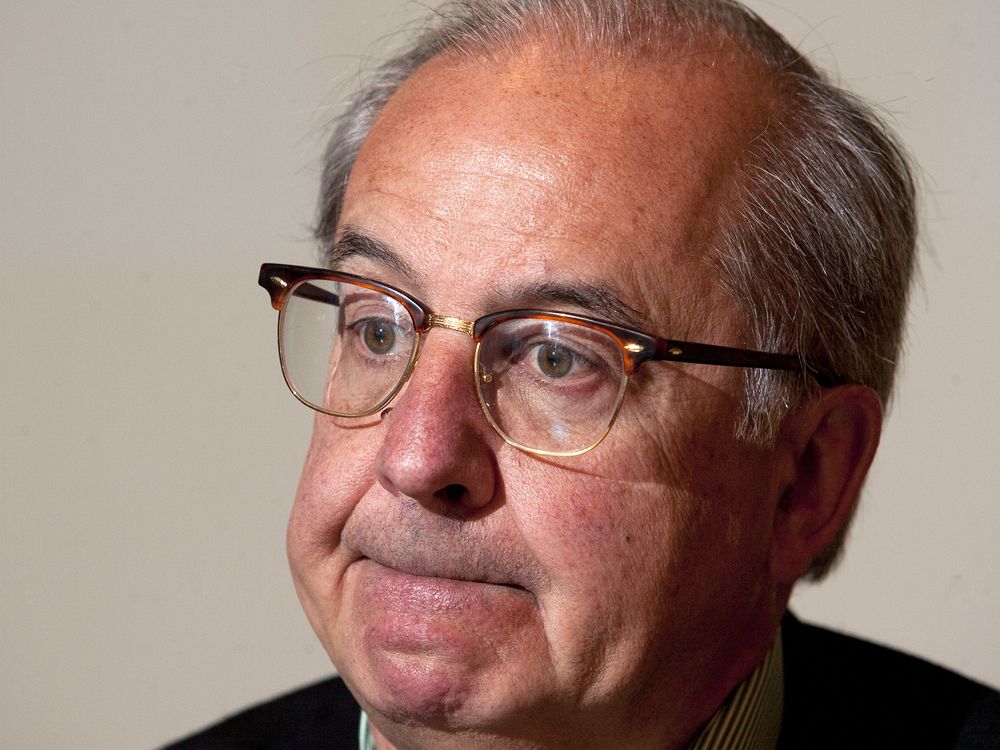

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Andrew Hale, an economist and trade expert based in Washington, D.C., is a citizen of both the United Kingdom and the United States, and a former resident of Canada, where he attended the former Grenville Christian College boarding school as a teen, and later CEGEP and Western University. Hale led a campaign to

expose abuses

against pupils at Grenville, having experienced them firsthand under the tenure of the headmaster, Rev. Charles R. Farnsworth.

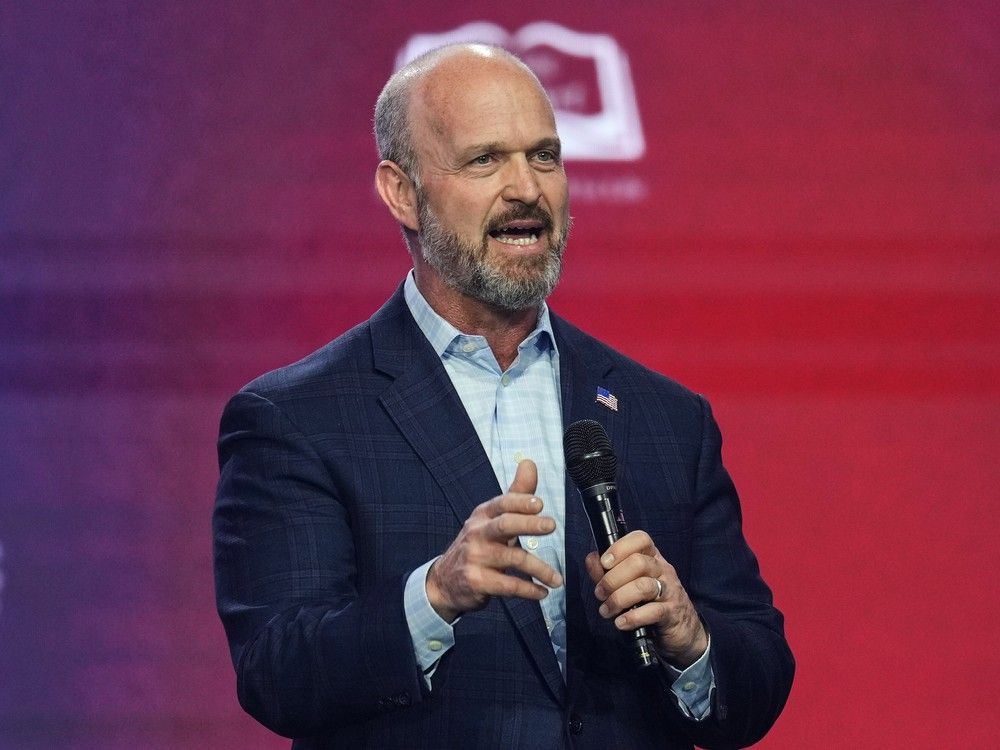

Since then, Hale has gone on to work for the U.K.’s Defence Intelligence Staff and Department for International Trade, the U.S. State Department, a U.S. congressman, and, most recently, for the Heritage Foundation. But this month, he resigned from the influential, Washington-based conservative think tank owing to his concerns over where the organization is headed under the leadership of its president, Kevin Roberts.

Roberts has fuelled headlines around the world in recent years, starting with his promotion of the Project 2025 project and culminating most recently in his defence of Tucker Carlson’s controversial interview with Nick Fuentes, who is often referred to as a white nationalist and antisemite. Roberts criticized the “venomous coalition” and “globalists” – some have speculated those were codes for Jews — of detractors for engaging in so-called cancel culture. In turn, the uproar over antisemitic rhetoric has led to donors, staffers, and board members fleeing the Heritage Foundation.

Hale just announced his own departure from the organization — he has taken a new role as a fellow at Advancing American Freedom — and wanted to share his thoughts on the worrying changes he has witnessed there in recent months with the National Post.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Several months ago, Kevin Roberts, the president of the Heritage Foundation, was set to speak to Canadian Liberal leaders about how to navigate their dealings with the Trump administration. The cabinet presentation was cancelled at the last minute. Why do you think that was? Did Trump have anything to do with it?

Yes, Kevin Roberts was going to speak… in Toronto for Mark Carney’s cabinet. At Heritage, we had an all-staff meeting, and Roberts said “I’m going to Canada, but don’t tell anyone.” It’s probably not a good idea if it’s a secret to tell the whole organization.

But [Heritage] didn’t understand how it works in Canada. The Carney government apparently put out some press release saying Roberts was coming, and there was such an outcry, with people asking, “Why would our prime minister meet with this guy?”

I don’t think it was a left or right thing. Trump’s not popular because of the way he treated Canadians, calling them the 51st state, etcetera, and the Liberal Party weaponized that unpopularity and managed to come back from the depths of their doldrums and form a minority government under Carney. They couldn’t believe their luck.

The whole Project 2025 thing didn’t help. It became quite famous in the United States and in Canada, but the 900-page book was written by a coalition of over 100 organizations, not just by the Heritage Foundation, and there are a lot of contradictions in it. While Heritage only contributed to about 30 per cent of that book, it was seen as the organization that was leading it.

Anyway, for the cabinet away day, I drafted a brief, as did another colleague. I set it up, and then I saw that [Carney’s team] had briefed the press. I think people at Heritage thought that this was going to be some sort of secret meeting, and it wasn’t. And I think they were alarmed when it appeared in the press. Carney’s cabinet was being open and transparent, announcing who’s coming to speak to them.

That led to Roberts cancelling and no excuse was given. I think he was just surprised that it had been publicly announced. I don’t think he understood the nature of what he was getting into. I think he thought he was going to go and have a meeting with Carney’s cabinet, and that it would be all under wraps and there would be no press invited and it would all be off the record.

So, once it hit the press, they basically just said this is not what we thought we were getting in to. There was a misunderstanding on both sides. One side was being very transparent and open about what the agenda was for the following day and who’d be speaking to them and who’d be coming. And on the Heritage side, it was supposed to be a secret.

And no, I don’t think Trump had anything to do with it. Since Trump disavowed Project 2025, there are no back channels between Roberts and the White House, so I doubt it was even on Trump’s radar. The Heritage Foundation used to be very influential under previous leadership, and they are still trying to live off that past reputation, but they are not very influential today. Individuals at Heritage have back channels to the Trump White House, but not the current leadership. One should remember that Kevin Roberts launched Project 2025 with Gov. Ron DeSantis during the primary. Roberts shifted his support to Trump when Trump won the primary and took down his anti-Trump posts about Trump’s adultery, January 6, etcetera.

Q: On your trips to Canada this past year, have you heard mostly positive things about Heritage Foundation, or have you felt targeted by negative association with it?

Fellow Grenville survivors have asked me, ‘how could you work for that cult?’ My publisher even received a call from a former a colleague, a professor in Canada, who said “don’t publish his books” because I was at Heritage. I’d worked with the woman when I was a civil servant, and she was impressed by my governmental service, but she wasn’t impressed with Heritage.

When I went to the throne speech at Ontario’s Queen’s Park and at the reception afterwards, I learned quickly not to mention the Heritage Foundation. Whether folks were in Doug Ford’s Conservative Party, the Liberal Party or in the NDP, if I said Heritage Foundation, they looked at me like I had a disease. I started saying I was an economist and trade policy analyst at a small think tank instead.

Because of Project 2025, which was so publicly associated with the Heritage Foundation, I have often heard that I was working for the vast, right-wing conspiracy — where it was at a school reunion, while visiting Canadian friends, or at conferences in Toronto or Calgary.

Q: You’ve just left the Heritage Foundation, where you worked as a trade expert for four years. Tell me what drew you to Heritage, why you decided to leave, and why you were drawn to Advancing American Freedom.

Populism lends itself to cult-of-personality worship. Before populism, we basically just had Democrats and Republicans, and they had different policy positions and they formulated policies. We don’t really do policy formulation the same way anymore because it’s at the mercy of the personality.

Take Trump, for example, he is unlike any other president — he’s not a typical politician — and I think that we’re going to go back to more traditional politicians when he leaves. You’re not going to see this populist movement the same way because there’s no one else who can do that and bring all these disparate groups together.

A lot of people who went to Grenville get really upset when they hear Trump, because they see Charles Farnsworth in him. I don’t necessarily see Farnsworth, but what I have noticed is that when you go to look at some evangelical mega-churches, it can become all about pastor so-and-so up at the pulpit preaching. There’s all this focus on the personality, and not about the policies and philosophy, and that’s exactly what I’ve seen happen at the Heritage Foundation.

Today, there’s less public policy formulation and more personality focus on Kevin Roberts himself — it’s the

Kevin Roberts Show

. Frankly, I think he should rebrand the Heritage Foundation the Kevin Roberts Foundation the way Trump renamed the Kennedy Center. There’s so much focus on the personality and the individual, and I don’t think that’s healthy.

Canada has a very good setup with the Westminster system of government, whereby the head of state is a sort of benign, somewhat removed monarch. People can have an affection, loyalty for that ceremonial head of state who embodies the constitution, and then they don’t really idealize the politician.

In the U.K. and in Canada, the prime minister is just seen as a politician, an administrator. You generally don’t have your whole national focus and patriotism wrapped up in that individual. But in the United States, the country becomes very divided when someone is in that role they don’t like.

Since Roberts became president of the Heritage Foundation, he’s made it personality-focused around him, and there’s little debate on public policy positions. It’s whatever he decides. A cult of Kevin Roberts has emerged around this messianic complex. I hear too much of this is, like what I heard at Grenville: ‘What does Father Farnsworth think about this? Would Farnsworth let us do that? Farnsworth is the closest thing we have to God. What does he think we should pray about today?’

I see a lot of people saying similar things at Heritage Foundation about Roberts, and it’s very worrying. ‘What does Dr. Roberts think? What does KDR say? Kevin says we can do this. Kevin says we can do that.’ That really brings me back to Grenville — there’s too much focus on that individual and on personality worship.

Then you add in all the God talk — Roberts invokes prayer at every opportunity. I’ve been in meetings where we have had to bow our heads in prayer. I’m not against prayer — I’m a practicing Anglican — and I have no problem with religion. But I have a problem with Roberts saying he’s willing to resign but won’t because God told him to stay to clean up the mess. When people start invoking God … perhaps it’s not God. Perhaps it’s just Kevin Roberts wanting to keep this a million-dollar-a-year salary.

When you start invoking God and saying God told you to stay, it’s very difficult to dial back from that.

God told you you had to stay? I think it’s ego speaking, not God.

There are some parallels to be drawn here with Grenville with regards to a personality-focused-based politics where the actual philosophy, the public policy, the conservative ethics and beliefs and values — their ideology — become second to whatever the personality that’s governing says.

The debate ends when one side says God told me so, so I am always right.

When I see Republicans who were defending free trade just a couple of years ago suddenly saying protectionism is great and it’s going to help us pay off the national debt, they’re simply saying everything the great leader says, regardless of their own beliefs. I saw that at what I call the cult at Grenville: A small group of people behind closed doors deciding for the whole organization.

I wasn’t consulted, for example, when Roberts put out his pro-tariff post last spring, and the whole economics department erupted in a massive rebellion. But it’s all about him and no one else, and the Heritage Foundation Board of Trustees are MIA and couldn’t care less.

That’s pretty much what happened at Grenville: One man took over the organization and it all became all about Charles Farnsworth and what he wanted. In both circumstances, it was justified in the name of God.

I first joined Heritage because of its legacy. I’d drawn from their work when I worked for Congressman Tom Lantos. I attended their events and thought they were excellent. They were normal, and I never knew what Ed Feulner’s (Heritage Foundation founder) religion was, and yet I’m sure his faith fuelled his moral framework and his decisions and how he operated. Religion can be a private matter — not to be weaponized in work meetings — and I’m aware that when I go to work, I’m in a multi-faith environment.

One of my former colleagues, an atheist, told me that since Roberts has come, she feels like she’s working in a weird church or cult. There’s nothing wrong with a church, but Heritage is supposed to be a non-sectarian organization, and by these people constantly invoking God to justify their positions in their actions, it ends any sort of debate or discussion. The same thing happened at Grenville; we weren’t allowed to criticize anything because God told them to do it. It’s very difficult to disagree with God, or with someone who claims God speaks through them.

Feulner, who died last July, was the last constraint on Roberts. Roberts never would’ve gotten away with making that video (the one where he defended Tucker Carlson for hosting Nick Fuentes on his show) — which is

still up on his X page

— and he would’ve been gone. The organization went so rapidly off the rails as soon as Feulner died.

Q: The recent antisemitism and misogyny scandals at the Heritage Foundation must feel distant to many Canadians, so why should they care? Does it signal a shift on the right in America?

President Trump said (in a recent) New York Times interview that he wants nothing to do with antisemites, and that they shouldn’t be in the party. He mentioned that his daughter and son-in-law and grandchildren are Jewish, that he’s the most pro-Israel president, and that he got some award from Israel. So he’s been very emphatic that antisemites have no business at all on the Republican side, the conservative side.

Well, I’d like to see someone like JD Vance say that. Vance says we shouldn’t be fighting and that there should be no division on the right. But no, that’s not right. We have to say that these people — Nick Fuentes, Tucker Carlson, Candace Owens — are objectionable people. People like them should not receive any invitations anywhere, to be a part of the movement or the Republican Party or conservative movement.

William Buckley Jr. was very clear: No John Birchers, no antisemites. Get people with these views and opinions out of the movement. Otherwise, we’re going to end up somewhere on the fringe.

We need to do the same thing again.

We’ve seen political figures on the left say some horrific things about Jews — Jeremy Corbyn, etcetera — and we always thought that was a problem for the left. But sadly, I’ve talked to some young people on the right who have said things like, oh, come on, the Holocaust didn’t happen. … Robert Maxwell, the father of Ghislaine Maxwell, purchased all the copyrights to all the textbooks we had to read in school and put that in there. I don’t think I believe in that anymore, or, if it did happen, it wasn’t that bad. It’s all been exaggerated.

They’re getting this on social media, where they’re following these nutters, antisemites, and bigots, and they’re believing these crazy conspiracy theories, which are easily proven by historical fact to be just that: conspiracy theories.

I recently spoke to someone who has quite a lot of influence with public policymakers and current elected officials, and we were discussing the national debt and how it is unsustainable. We talked about historical examples of unsustainable national debt, and this person shocked me when she said, ‘Well, in the 1930s, the Jews kept lending the money and everyone got into debt, and Hitler came along and just tried to save everything, and Winston Churchill was the villain who caused World War II.’

I was actually speechless. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing, and then she casually said she had to cut our meeting short and collect her child from school.

So, yes, I do feel that there is a problem on the right.

Q: Heritage has seen several trustees like Abby Spencer Moffat resign over its handling of the antisemitic controversy involving Tucker Carlson’s interview. How has this internal realignment on the right affected the foundation’s work? Why do you believe the board is letting Roberts stay, despite the mass exodus of staffers, including yourself?

It was hard for the board at Grenville to believe that Charles Farnsworth was an

abuser

. These were wealthy and powerful people who were drawn into the school. They didn’t want to believe it. I think it’s the same for the board at Heritage. I see a lot of parallels. When you have an organization that becomes heavily personality-based, you get the cult group think. They also did not want to believe that they had been played for fools by a man like Charles Farnsworth.

When we have struggle sessions at the Heritage Foundation and we’re told we have to sign up to every single thing that Roberts believes and everything that’s decided at the top, we’re no longer having debates, and that’s dangerous. In previous Heritage presidents’ time, there were robust policy debates, we learned something from each other, and we vigorously defended our positions. We had the debates, and it was necessary to come out at the other end with a firm position if you’re going to have a one-voice policy.

I’m glad you mentioned the board, because at the end of the day, the buck stops with them. They are legally responsible for the Heritage Foundation and the staff. Where are they? Why haven’t they hired a crisis management firm to come in and immediately take control of the organization? That’s what you do in a crisis.

Whatever we have in-house and whatever we’re doing in-house isn’t working. I just think that it’s a part of the human condition — it’s just easier to ignore the problem and sweep it under the carpet. I’ve heard things like “oh, it’s so hard to have another executive search for a president. It was so difficult last time.” Or, “oh, it’s Thanksgiving, the holidays. We don’t want to do this right now.”

Over the past few months, five board members have resigned, and some have put out very robust resignations and cited the recent antisemitic controversy at Heritage as their reason for leaving.

But as for the board’s inaction, I just think it’s a question of not caring and not wanting to deal with a problem. But the buck stops with the board, and they have clearly failed. They need to wake up, do their duty, and stop drinking the Kevin Roberts Kool-Aid. It does not help that Roberts sits on the Heritage Foundation Board of Trustees. They have little interaction with the staff and do not know what a psychodrama 214 Massachusetts Ave North East has become.

National Post

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our newsletters here.