While E.M. spent most of her 20s regretting the night she spent with some members of Canada’s 2018 world junior hockey team (and for which she received a lucrative settlement from Hockey Canada), those members spent those same years wondering whether their 30s would take place in jail.

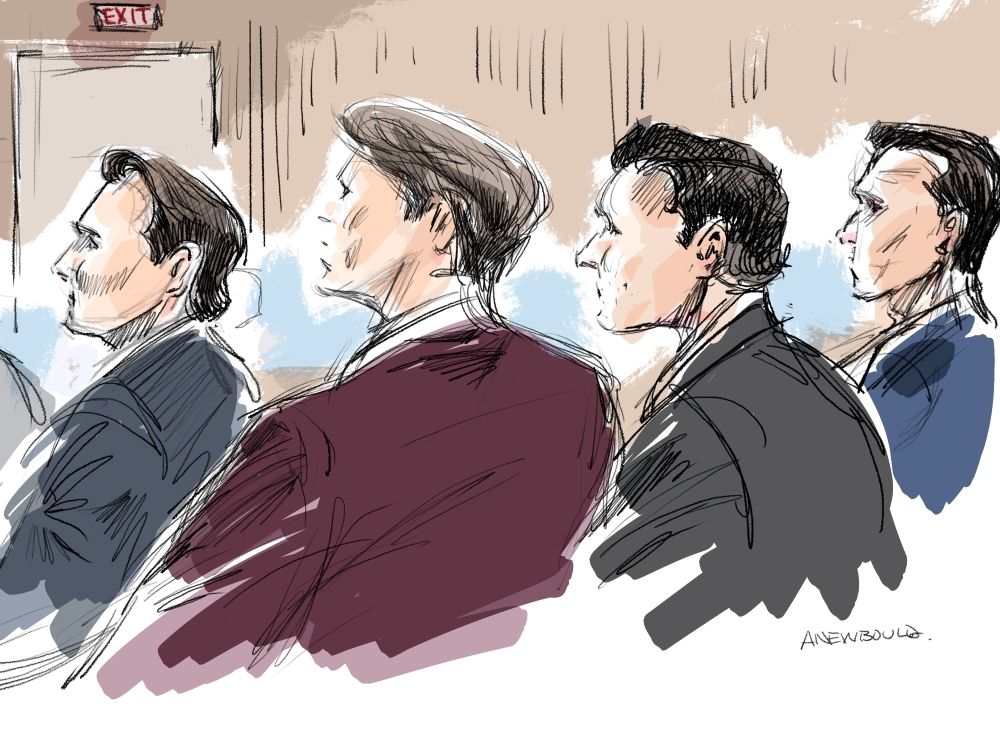

At very least, some justice was done on Thursday when the five players on trial for sexual assault were found not guilty. E.M., ruled Ontario Superior Court Justice Maria Carroccia, had in fact consented. At the trial stage at least, the system didn’t “believe all women”: there was a pile of evidence showing that E.M. not only consented but may have initiated the evening’s events, and it was given the fair consideration it deserved.

On a careful review of the facts — which were largely derived from E.M.’s and the players’ accounts of that night, minus all the extra evidence that was excluded from trial due to Canada’s special evidence rules for sex assault — Carroccia had to consider whether E.M. was touched in a sexual way, and whether there was an absence of consent during that contact. That answer would come down to the credibility (truthfulness) and reliability (capability of accurately remembering what happened) of each witness, E.M.’s being the most critical to securing a conviction. But E.M., the judge determined, was neither credible nor reliable.

According to Carroccia’s lengthy written decision, then-20-year-old E.M. had been clubbing with friends in the early hours of June 19, 2018, when she clicked with the team’s Michael McLeod and withdrew to his hotel room to have sex, cheating on her boyfriend in the process. Some time after that, McLeod invited other teammates to his room (E.M. couldn’t say whether it was her idea or not) and she became the centrepiece of a post-club team afterparty. This didn’t help her case: defence pointed out that infidelity was a motive to fabricate.

Carroccia identified other problems going to the complainant’s testimony: she was intoxicated, which impacted her memory (though not too drunk to consent, as everyone agreed that her first bout of sex with McLeod was consensual); she didn’t remember certain key events of the night, and filled those “gaps” with assumptions (some of which were contradicted by hard evidence).

This wasn’t the justice system being cruel and unfair to women. It was the regular kind of scrutiny that we apply to alleged assault victims as a safeguard against imprisoning people for colourful stories about crimes they didn’t commit.

“The evidence of each of the witnesses has gaps and does not constitute a complete or sequential recounting of the events,” the judge explained, in the context of Carter Hart’s charge (a similar statement was made for each accused teammate).

“I have concerns regarding the credibility and reliability of the evidence of the complainant, and therefore I have a reasonable doubt about whether the complainant consented to the sexual activity with Mr. Hart.”

The loud hotel party was powered by the naked woman who had, at some point, taken up residence on the floor, where a sheet had been placed (by E.M., according to the players; by the players, according to E.M.). There, the judge’s ruling recounts, she demanded sex and called the surrounding 19-or-so-year-olds “pussies” when they refused. At trial, she agreed with one player’s assessment that she took on the persona of a porn star.

“I accept the overwhelming evidence that E.M. was acting in a sexually forward manner when she was masturbating in this room full of men and asking them to have sex with her,” assessed Carroccia. “This evidence alone does not establish her consent to engage in oral sex … but it does establish that she communicated her willingness to engage in sexual activity.”

But E.M. was mostly met with rejection: one player called as a witness testified that his teammates were shocked at the woman’s boldness, and that the group awkwardly laughed at her “offers.” Dillon Dubé noted in his police statement that most of the men were just talking as many had girlfriends. Both Hart and E.M. testified that the men egged each other on. Nobody seemed to want to have sex in a room with other people.

Eventually, some agreed. Alex Formenton “volunteered” on the condition that the intercourse take place in the bathroom, according to his police statement. Hart, who was single and initially drawn to McLeod’s room at the prospect of a three-way, testified that he was enticed by E.M.’s overtures; after less than a minute of oral sex, he quickly felt weird about it and pulled back. E.M. also gave oral sex to two others: Dillon Dubé, for 10 seconds according to his police report (he also instantly didn’t want it), and McLeod, briefly, according to two player witnesses. In a “consent video” taken around this time, E.M. smiled and stated, “I’m okay with this.”

The video wasn’t definitive proof of consent, wrote Carroccia, but it was part of the equation: “In my view it is circumstantial evidence as to the manner in which she was behaving. The first video was taken without her knowledge, so it presumably depicts how she was behaving at the time. She was speaking normally, she was smiling and did not appear to be upset or in distress. She did not appear to be intoxicated.” The Crown had argued the video was

to the question of consent.

Two player witnesses agreed that at some point, Dubé slapped E.M.’s butt. She also reported that a player — Callum Foote — did the splits over her face while naked, but no one else testified to contact or to pantlessness. Hart testified that Foote was over E.M.’s torso, and she was laughing.

E.M. would become upset and frustrated at the lack of sexual advances, said some of the men, and McLeod even calmed her down at one point, according to his police report. E.M. testified that she cried at least once (either because of the men’s comments or because they were laughing at her). Two men, called as witnesses, were so uncomfortable with the situation that they left.

The party wound down after 4 a.m., and E.M. had sex with McLeod one last time in the shower — an act, she told the court, she felt was necessary to get him to allow her to leave. He recorded one more video. “It was all consensual,” she said, multiple times, smiling. “Would you … You are so paranoid, holy. I enjoyed it. It was fine…. I am so sober that’s why I can’t do this right now.” Together, these rendered E.M.’s evidence “vague and inconsistent.”

She didn’t leave happy, though: towards the end, McLeod asked her if she had STDs, and whether she was going to be leaving soon, which she felt was rude. E.M. also testified that McLeod also seemed annoyed at her when she returned to the room to search for a lost ring; she took an Uber home and was found crying in the shower by her mother, who “took it upon herself” to report a sexual assault to police.

E.M. later explained to the court that her actions were driven by fear — fear that she never mentioned until she filed a civil suit against Hockey Canada, four years after the fact. Her mind “separated” from her body to cope, she claimed. The judge didn’t buy her story: important details had changed over time, and E.M.’s own concept of truth was uncomfortably fuzzy. Plus, E.M. initially told police that she didn’t think the men would have physically forced her to stay.

The judge didn’t hypothesize the complainant’s actual feelings about what happened, but I suspect E.M. was quite miserable. She may have felt shame and regret for cheating on her boyfriend, as the defence argued during the trial. The little oral sex that was had was awkward and not erotic at all. The STD question may have felt like an accusation.

Pop culture tells women that consensual sex is a neutral to empowering act, and good feminists will tell their friends that there’s nothing to be ashamed about in sex. Slut shaming, we all knew in the good year 2018, was bad. But missing from that intense belief in female agency was the other side of the coin: that women can consent to something and wish they hadn’t.

And certainly, the men regret it too. Their evidence suggested they took care to ensure consent was given at the time, and even that wasn’t enough to keep an investigation from pausing, perhaps snuffing out, their NHL careers. McLeod and Foote were

last year by the New Jersey Devils, as was Hart by the Philadelphia Flyers and Dubé by the Calgary Flames. And in 2022, Formenton

have lost out on a new contract with the Ottawa Senators due to the allegations; he played in Sweden until the charges were laid in 2024, and now

. As for the future of these five men, the ball is still in the Ontario Crown’s court. Prosecutors will have to decide in the next month whether to appeal for another shot at securing convictions; there’s still a way this can drag out for years.

Supporters of E.M. will say the acquittals amount to a terrible outcome for women and sexual assault survivors, but they’re the opposite. If sexual assault is to be taken seriously, it needs to mean something. It’s to the actual victims’ benefit that Carroccia didn’t bend the rules to acrobatically extend the concept of sexual assault to new frontiers of apparently regretful intercourse, as courts have done in the past; doing so would have cheapened the concept to dollar store levels.

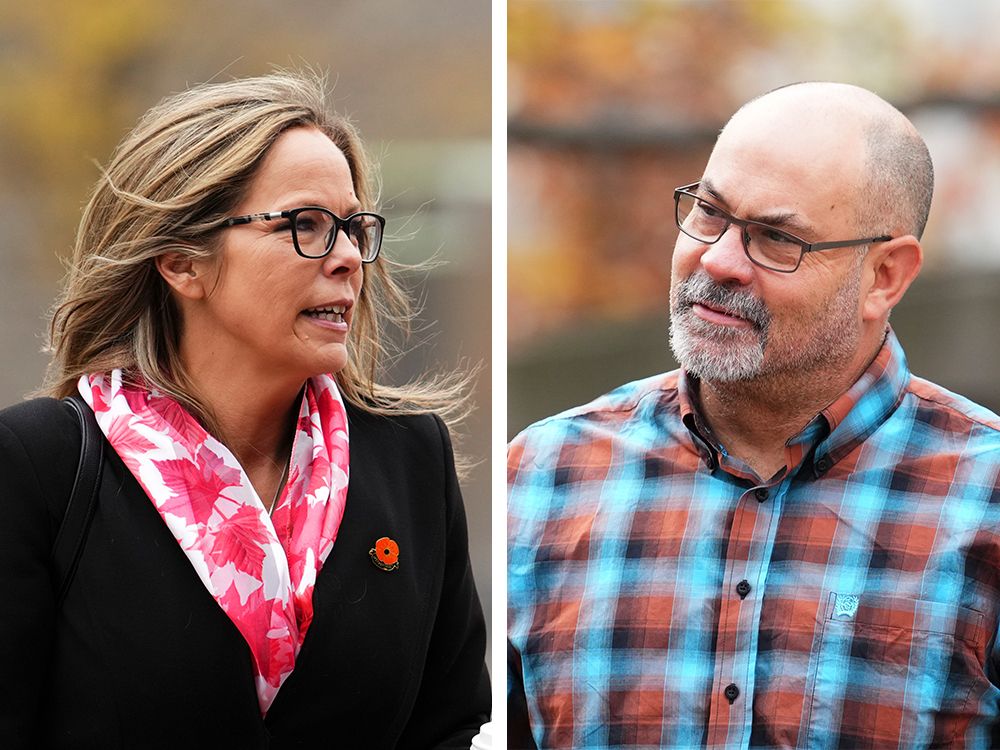

So, now what? After the decision was read, E.M.’s lawyer, Karen Bellehumeur, immediately took to calling for reform. “While the accused’s rights are important, those protections should not come at the expense of survivors’ well-being,” she

a media scrum late Thursday. She expressed frustration with the fact that E.M. had to testify for nine days and was subject to “insulting, unfair, mocking and disrespectful” cross-examination. “She’s really never experienced not being believed like this before.” Nine days of careful scrutiny is a very modest ask when a man is facing jail for an apparently consensual act that didn’t pass the initial police sniff test.

It’s one thing to be of a tough-on-crime mind; it’s something else to believe that the pursuit of truth should be compromised.

National Post