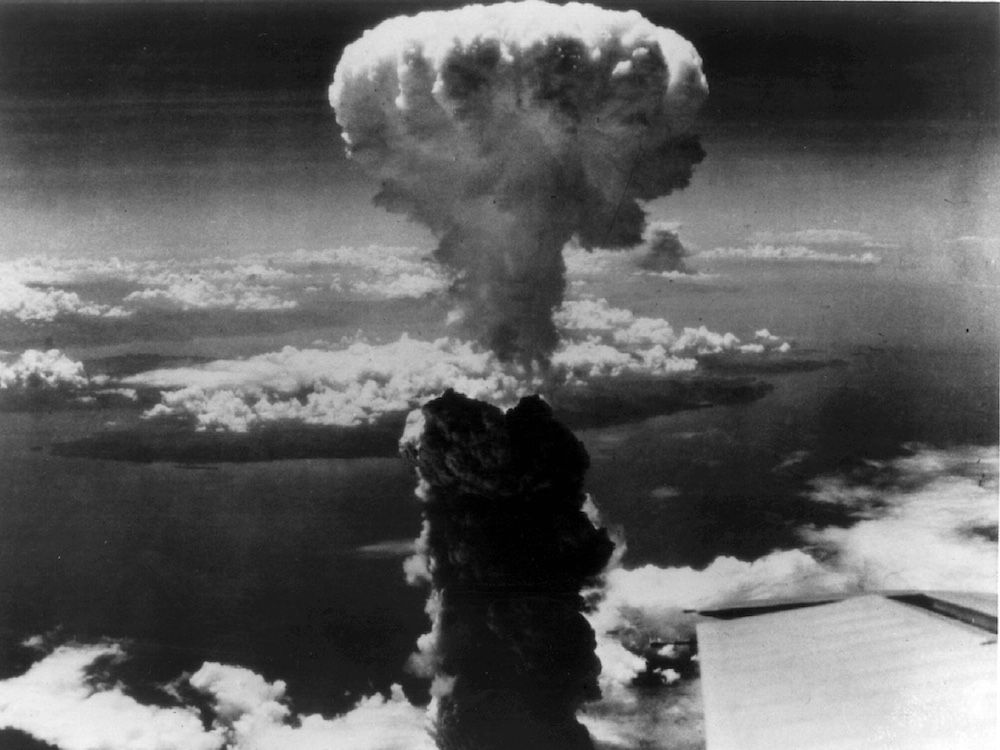

For pacifists, the answer is clear: since any deliberate killing is wrong, the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945 was wrong about two hundred thousand times over. Which rather complicates any celebration of Victory over Japan Day.

But that clear answer generates further questions whose answers aren’t so obvious. If killing is always wrong, then the United States should never have gone to war against Imperial Japan and therefore its ally, Hitler’s Germany. What, then, would have stopped the triumph of brutally racist Japanese imperialism in Asia and massively murderous Nazism in Europe? The noble witness of innocent non-violence?

Unfortunately, the historical evidence is that the kind of people who ran the slave-labour camps in Burma, and the likes of Dachau in Germany and Auschwitz in Poland, were not at all shamed by the face of vulnerable innocence; on the contrary, it excited their lust for domination and they fed upon it. No one who has watched the dreadful beating to death of an Australian POW in the tv dramatization of Richard Flanagan’s

The Narrow Road to the Deep North can doubt it.

On the other hand, those who think that war can sometimes be justified, might judge that the mass killing of civilians by the atomic bombs was, simply by its massive extent, indiscriminate and therefore unjust. But there are two problems here. The first is that the vast majority of people — certainly in Anglo-Saxon countries such as Canada, Britain, and the U.S.A — regard the war against Hitler and his allies as morally justified, notwithstanding the fact that it cost between 60 and 80 million deaths, well over half of them civilian.

And the second problem is that the ethical tradition of “just war” thinking doesn’t say that we may not kill civilians, even on a massive scale; it only says that we may not kill them intentionally. If a military objective can’t be achieved except by risking the possible or probable deaths of civilians, then it may still be attempted, provided that the objective is sufficiently important, militarily, and that all reasonable measures are taken to avoid or minimize the side-effect of civilian casualties. The reason for this permissiveness is that in most circumstances just war would be impossible to prosecute otherwise.

So, for the “just war” proponent, if the intention in dropping the atomic bombs on Japan was to destroy vital military or military-related targets, and if there was no more discriminate way of achieving that end, then the bombing was morally justified. It was deeply, deeply tragic — but nevertheless just.

If, however, the intention in dropping the bombs was to slaughter Japanese people indiscriminately out of sheer vengeance, then that would be clearly immoral — since the motive of vengeance is always forbidden. Also immoral would be the use of the indiscriminate slaughter of civilians to terrorize the Japanese government into surrender. Why? Because if it’s morally OK to use non-combatant civilians in such a “terroristic” fashion, then no limits remain upon what we may do in war.

Which of these hypotheses best fits the facts of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is a matter of historiographical controversy. When I last wrote on this topic — to mark the 70th anniversary in 2015 — I said this: “For what it’s worth, my own amateur impression is that … the intention in dropping the bombs was more ‘political’ (or terroristic) than military. If that is so, then they shouldn’t have been dropped.” Now, however, having read Evan Thomas’ detailed account of the decision-making processes in both Washington and Tokyo (Road to Surrender: Three Men and the Countdown to the End of World War II [London: Elliott & Thompson, 2023]), I’ve changed my mind.

Vengeance had nothing to do with it. The overriding motive of the U.S. government was the desire to save the lives of war-weary Americans by bringing the war to a swift end, through forcing the Japanese government to surrender. Two weeks before the first bomb was dropped, President Truman wrote: “My object is to save as many American lives as possible but I also have a humane feeling for the women and children of Japan”.

The problem facing the president and his colleagues was that, even as the Japanese were forced back onto their home territory, they showed no sign of giving up the fight. They still had about five million troops in and out of uniform all over Asia. In Japan, all men aged 15-60 and women aged 17-40 had been enlisted in a National Volunteer Corps, armed with muskets, spears, and pitchforks. The Japanese were intent on bleeding the Americans dry as they invaded.

In July U.S. casualties (dead and wounded) while invading the outlying island of Okinawa were 50,000 and rising. Truman’s military advisors estimated that the invasion of the Japanese mainland in November would cost up to 1 million casualties (dead and wounded). One alternative was to blockade Japan, but that would have entailed starving the civilian population. It would also have taken a long time and General Carl Spaatz, the U.S. Army Air Force commander, was keen not to prolong the firebombing of Japanese cities, which had killed at least 85,000 people in Tokyo, most of them civilian, in March.

Therefore, the U.S. government decided on the only other alternative: to use the newly developed atomic bombs to intimidate the Japanese into surrender. The possibility of a “demonstration” drop onto some sparsely populated desert or island was considered, but it was rejected because, at the time, the Americans only had two bombs and had never dropped such things from the air before. If the demonstration failed to have the desired political effect and the follow-up went awry and proved a dud, there would be no bombs left. So, the decision was made to bomb cities.

What considerations were involved in deciding which cities to bomb? Was the size of population one? No. The focus was on military and economic objectives. The historic city of Kyoto was ruled out by Henry Stimson, Truman’s secretary of war, since it was sacred to the Japanese and its destruction would have excited such bitterness as to impede postwar reconciliation. Hiroshima, on the other hand, was known as a “military city” by the Japanese themselves. It housed the army headquarters for forces defending Kyushu, the southernmost island of Japan, which was the first target of U.S. invasion. It also had several small shipyards, supply depots, and some industry on the periphery. Nagasaki was a port town with munitions factories.

Tragically, precise targeting was not an option. Due partly to technological limitations and partly to persistent cloud-cover, U.S. attempts at the precision-bombing of factories and industrial targets in Japan had generally failed. Moreover, those sites were often widely dispersed in residential districts. Therefore, Truman’s Target Committee decided to aim at Hiroshima’s city-centre, not least because there was a prominent bridge there that would be easiest to spot from 30,000 feet. The result? 70,000 people were killed directly, with a further 70,000 indirectly.

But was it really necessary to drop a second bomb? Yes, it was. The atomic explosion in Hiroshima failed to persuade Japan’s government to surrender. So, three days later, on Aug. 9, another U.S. bombing mission took to the air. Its intended target was in fact Kokura, whose centre hosted an enormous arsenal. In the event, however, Kokura was obscured by cloud-cover, so the bomber proceeded to the secondary target of Nagasaki. For reasons that remain unclear — the city was not hidden by cloud — it dropped its bomb over two miles from the city-centre and hit a Mitsubishi armaments plant. Nevertheless, 40,000 people were killed.

Even after the bombing of Nagasaki, the Japanese war minister, General Korechika Anami, was still arguing in favour of fighting on to the bitter end. “We will find life out of death,” he said. “Wouldn’t it be beautiful?” Fortunately, his counsel didn’t prevail. Finally— eighty years ago today, on Aug. 15 — the Japanese government decided to surrender.

In the light of these facts, what should our moral assessment be? We can certainly say that the two atomic bombs were not dropped to wreak indiscriminate vengeance upon the Japanese people. On the contrary, they were dropped to bring the war to a swift end, thereby saving American (and Allied) lives primarily, and Japanese lives secondarily. That was the ultimate intention.

But what about the proximate one? Was the mass killing of civilians intended as the means of terrorizing the Japanese government into surrender? I don’t think so. The likely number of civilian casualties does not seem to have been a reason for the bombing. Desert and island targets, entirely or largely unpopulated, were considered. And they were set aside, not on principle, but for prudential reasons. The reasons for the choice of the eventual targets were military and economic. Had it been possible to hit discrete military and industrial sites of sufficient importance, without endangering civilian life, those, I believe, would have been preferred. But it just wasn’t possible.

Therefore, tragically and dreadfully, the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was morally necessary.

Nigel Biggar, CBE, is Lord Biggar of Castle Douglas, Professor Emeritus of Moral Theology at the University of Oxford, and author of

In Defence of War

(2013).