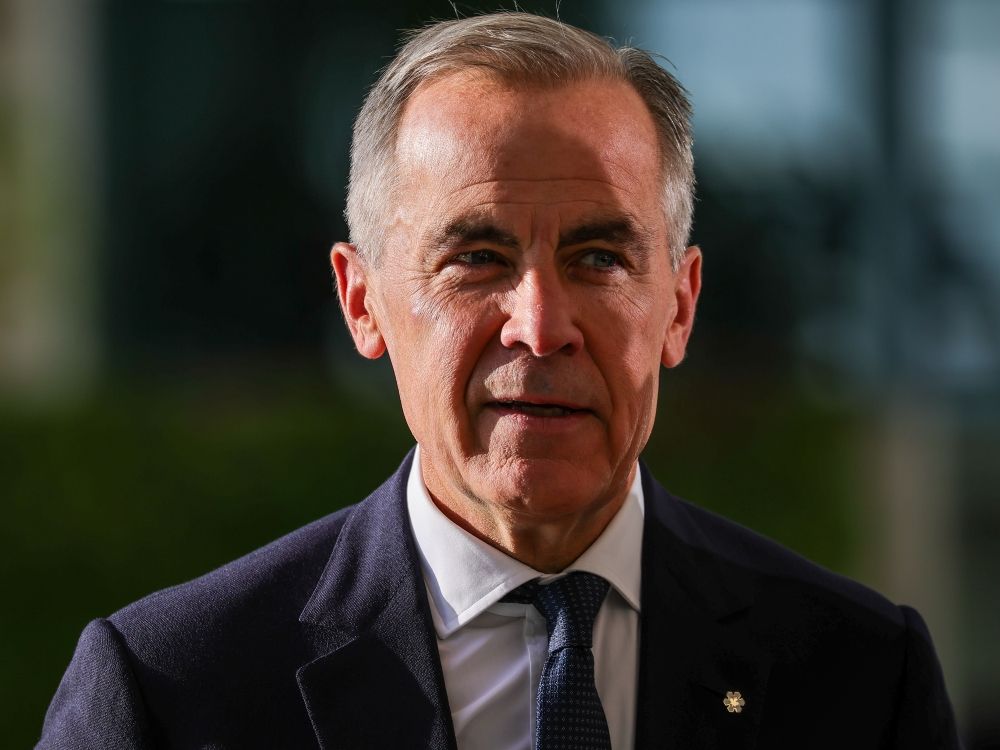

Mark Carney’s been busy these past few months, hosting the G7, pursuing foreign trade pacts, and talking with Trump on the telephone. But instead of a reset, he’s had a summer of discontent, putting us back at square one with the Americans and facing a host of challenges for the fall.

After weeks of tariff tit-for-tat with Washington, including

dropping the digital services tax

, the Aug. 1 trade deal deadline came… and went. Instead of a deal, Trump whacked Canada with some of the highest general tariffs in the world. Steel and aluminum tariffs remain in effect. Carney then blinked on the big issue: in late August, he announced Ottawa would lift most of its retaliatory tariffs on U.S. goods, in hopes of reviving talks — and, no doubt,

lowering consumer prices

as

recession looms

.

The problem? Nothing’s come back. Trump’s trade team has offered no concessions, no guarantees, not even a timeline. And the president is still hell-bent on

protecting American steel producers

at the expense of Canada.

On a parallel track, Carney has been working hard to diversify trade, reaching out to Japan, the EU, and emerging markets in Southeast Asia. That makes sense, but diversification is no quick fix, and no full long-term fix either. Geography and economics dictate that America will always be Canada’s main market, accounting for three-quarters of our exports: trading with the rest of the world is simply more complicated and more expensive.

Which brings us to the big elephant — or rather, dragon — in the room: China. After this weekend’s

Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit

, President Xi Jinping is riding high. He bonded with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Monday, inked a

Siberian oil deal

with Russian President Vladimir Putin on Tuesday, and is spending Wednesday showing off China’s military might to the leaders of Turkey, Iran, and North Korea, at

a massive military parade

in Beijing — at which western leaders are conspicuously absent.

These events underscore China’s ambitions as the anti-America, actively

challenging the hegemony of the West

and offering economic shelter to countries burned by Trump’s tariffs and sanctions. This leaves Canada between a rock and a hard place: as Beijing puts the squeeze on our canola farmers and seafood producers, pressure is mounting for Canada to review our ban on Chinese EVs, imposed in line with U.S. policy. Unless Ottawa can get a deal with Washington, those calls will just get louder.

So, what should Carney do now? Here are three things he must tackle this fall.

First, renegotiate CUSMA

.

Carney must get a new deal that focuses not just on tariff relief, but on predictability and enforcement mechanisms. Yes, Trump can change his mind in five minutes, but without a functioning U.S. trade relationship, everything else is window dressing.

Second, diversify where it makes sense. Canada needs a targeted, not scattershot, approach, fast-tracking deals with markets that can actually deliver, where Canadian agriculture and energy have a chance to compete.

Third, put security before sales. Ottawa can’t mortgage national security to trade with China. The ban on EVs isn’t about market share or U.S. alignment: it’s about spyware. From critical minerals to telecoms, security concerns must come first, period.

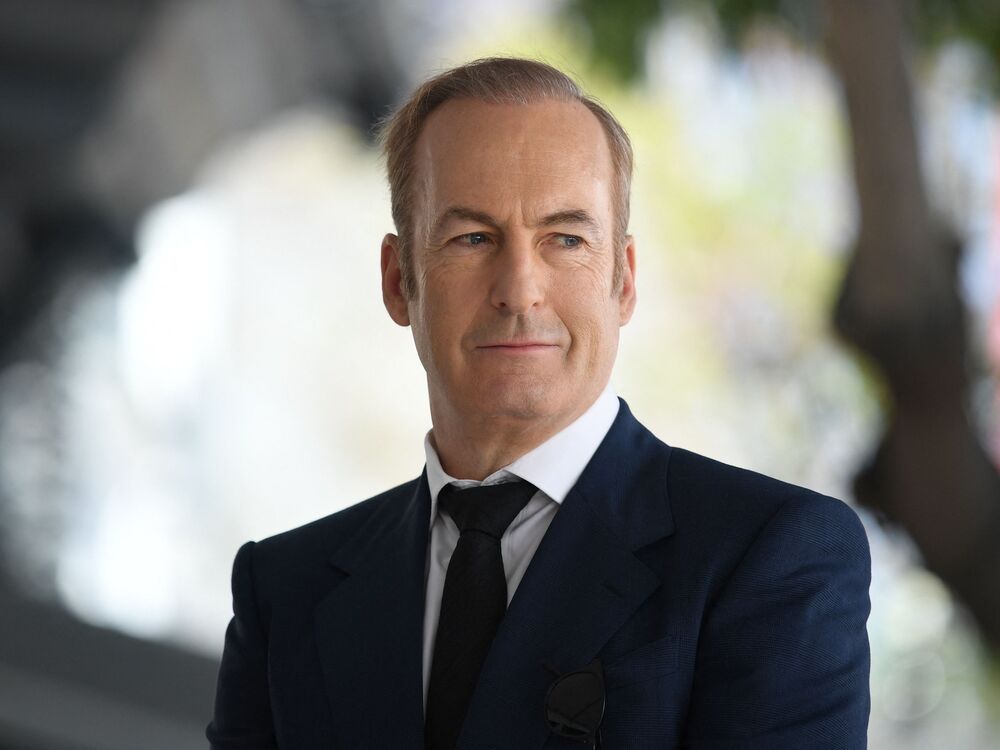

Can Carney pull these things off? Watch for the Opposition, including returning Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre, to press that question this fall. And with good reason. Carney won this year’s election on the presumption that he was the best leader to tackle Trump. He presented himself as the polished technocrat, at ease in the corridors of power, projecting calm under pressure. And of course, he wasn’t Justin Trudeau.

But navigating trade wars isn’t the same as stewarding central banks. And so far, the government’s strategy has yielded squat on our most important file. With Trump playing hardball, Xi playing longball, and the rest of the world scrambling to save the furniture, Carney needs to up his game — or pay the political price.

Postmedia News

Tasha Kheiriddin is Postmedia’s national politics columnist.