In the final chapter of Harvard Professor Michael Sandel's 2020 book, The Tyranny of Merit, he suggests, "The injury that most animates the resentment of working people is to their status as producers… Only a political agenda that acknowledges this injury and seeks to renew the dignity of work can speak effectively to the discontent that roils our politics."

He writes about a sense that those without a Bachelor's degree feel adrift, stripped of their status as blue-collar jobs no longer provide job security, pay and benefits sufficient to be a breadwinner for one's family.

He ties this sense of economic and status insecurity to the election of Donald Trump and Brexit, but also more broadly to a sense that "A four-year degree has become the key marker of social status, as if there were a requirement for nongraduates to wear a circular scarlet badge bearing the letters BA crossed through by a diagonal red line". He quotes Michael Young's observation as well that "'in a society that makes so much of merit' it is hard 'to be judged as having none. No underclass has ever been left as morally naked as that'."

Sandel goes as far back as Aristotle, who "argued that human flourishing depends on realizing our nature through the cultivation and exercise of our abilities." He also quotes Pope John Paul II as saying that "through work man 'achieves fulfillment as a human being'."

Yet, for me reading this book over a year into the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns, it was particularly striking to think of the sense of being without a purpose in life, trapped at home unable to work. We're all going a bit squirrely with our lives interrupted, our usual social activities curtailed. But for the millions who find themselves unemployed or unable to go into work or running a business at reduced capacity with fewer staff, there is a devastating psychic impact to our sense of self.

Millions of Canadians can no longer hold to their status as employer — the woman or man who led the company and looked after their employees — or to their status as a valuable worker, responsible for making something with their hands or being an integral part of the operation. Instead, millions are left to rely on government support, and find navigating the system perplexing.

Robert F. Kennedy suggested, "Unemployment means having nothing to do — which means having nothing to do with the rest of us. To be without work, to be without use to one's fellow citizens, is to be in truth the Invisible Man of whom Ralph Ellison wrote." RFK also said, "Fellowship, community, shared patriotism — these essential values of our civilization do not come from just buying and consuming goods together [but from] dignified employment at a decent pay, the kind of employment that lets a man say to his community, to his family, to his country, and most importantly, to himself, 'I helped to build this country. I am a participant in great public ventures'."

As the economy begins to reopen hopefully this spring, we need to recognize this sense of alienation and loss of status. "Building back better" does not simply mean investing in better infrastructure or a greener society.

It has to include real, meaningful recognition of the people lauded as frontline workers — the largely immigrant women who serve as personal support workers to the elderly and disabled, the sanitation engineers who keep the basic plumbing of society working, the minimum-wage workers who stock grocery shelves, the truck drivers and Amazon warehouse packers who get goods to their destination.

Whether through higher wages or better benefits, whether through some form of a basic income to provide granite beneath everyone's household budget (what we have already for seniors with our public pensions or children with our child benefits), the project of building back from COVID-19 has to recognize not only the dignity of work, but the need for society to give everyone a fair shot, yes, but also a new social contract that says categorically we will not let people slip below a certain, basic standard: that hard work will be rewarded with a sense of self, that everyone will have a basic floor.

The lesson of the pandemic has to be that as a society, we came together to ensure everyone had some form of a social safety net to catch them — and that such basic security cannot be limited to bad times, but should become a new foundation for us all.

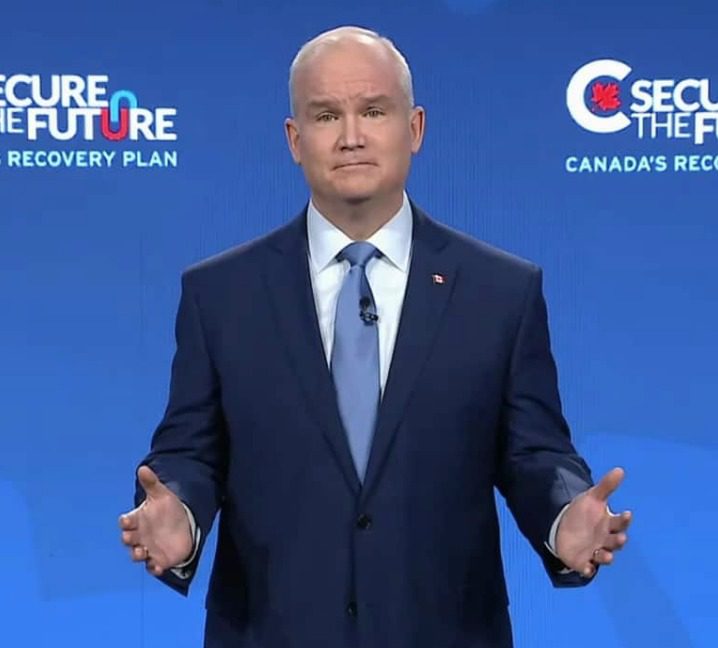

Photo Credit: The Nova Scotia Advocate