After what seemed like an eternity of dispirited, phantom leadership, Andrew Scheer and his insipid reign of mediocrity are no more.

At the Conservative leadership convention in August, Scheer made his final public appearance as leader, delivering his farewell speech just hours before his successor, Erin O'Toole, secured control of the party in a stunning electoral upset.

As the outgoing head of the party, Scheer's speech was arguably his last chance to leave a positive stamp on his legacy as Opposition leader. It was also his last opportunity to do the Conservative Party any last-minute favours before he stepped off center stage and disappeared into obscurity, becoming just another nobody MP as Pierre Trudeau would have said.

If written well, and delivered with palpable enthusiasm and excitement, Scheer's speech could have energized his party and strengthened Conservative unity. If successful, it could have also helped encourage apathetic or non-partisan Canadians to take a second look at the party, come the next election.

For that to happen though, Scheer would have had to have been gracious and courteous. He would have also had to have been eloquent, articulate and inspiring.

Scheer, however, was none of these things.

In his final address as party leader, Scheer delivered a speech that was both vengeful and vindictive, hyperbolic and hyper partisan, and chock full of analogies that might have been laughable if they had not been so preposterous.

Throughout his oration, Scheer made many absurd claims. At one point, he declared that "Conservatives are the only party fighting for hard working Canadians." At another, he stated that "ever increasing intervention in the marketplace rewards big corporations who can afford expensive government relations experts." Cue the eye-rolls.

He also whined incessantly about everyone from the "establishment elites" to the "mainstream media" to the unions, who he charged with conspiring behind-the-scenes to defeat him and his party. For a political organization that really loves to hammer on about the importance of self-reliance, they really revel in self-pity.

Apparently, they also revel in cliché illusions, which Scheer weaved throughout his speech on more than one occasion. In one instance, Scheer boasted that Conservatives provide voters a "balanced meal" in comparison to the Liberals "who are all candy before supper." I do not know if Scheer aimed this portion of his speech at elementary students, but even they would not have been impressed by such a lame performance.

Finally, and most egregiously, Scheer took a trip back in time to the Cold War of the 1980s, ominously comparing the rhetoric and policies of the Soviet Union with that of the Canadian "Left" (a.k.a. all the other major federal political parties). He even went as far to conjure up dire images of the "bread lines in east Berlin" all in an unsuccessful attempt at fearmongering against his political adversaries.

It was all kind of sad really.

Faced with the collapse of his political ambitions, lacking in policy prescriptions, and unable to consider a path forward in this new deficit-spending era, Scheer could do nothing but revert to the scare-tactic language of his Cold War heroes, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. I almost felt bad for the guy.

By that point, though, Scheer was wrapping up his speech and preparing to exit offstage. With COVID restrictions in place, the convention centre did not have much of an audience present, leaving the whole room oddly silent for his closing act. Once again, I almost felt bad for the guy.

Before I could, though, I came to realize that nothing other than silence would have been appropriate for a speech as uninspiring and low calibre as Scheer's. While I do not wish ignominy on anyone, his exit, free of any applause or curtain-calls, was probably for the best.

Hopefully as he returns to his previous life as an MP, Scheer can take some comfort in his achievements, particularly that he increased the party's seat count and helped consign the Liberals to a minority government. That in itself is an accomplishment no one can take away from him. Not even his largely imaginary enemies in the establishment elite and mainstream media.

For a party in the midst of an identity crisis, struggling to reach consensus on a whole host of issues (prioritizing climate change, LGBTQ+ rights, etc.) the Conservatives require a far competent and thoughtful leader; one with the capacity to leave their rigid, intellectual predispositions behind and project a new vision for the country. Not one that looks back (at the 1980s of all times) in the hopes of finding solutions for the unprecedented challenges of the future.

I do not know if O'Toole is the leader Conservatives need in this moment. But after listening to Scheer's farewell speech, it is clear they could be doing a lot worse.

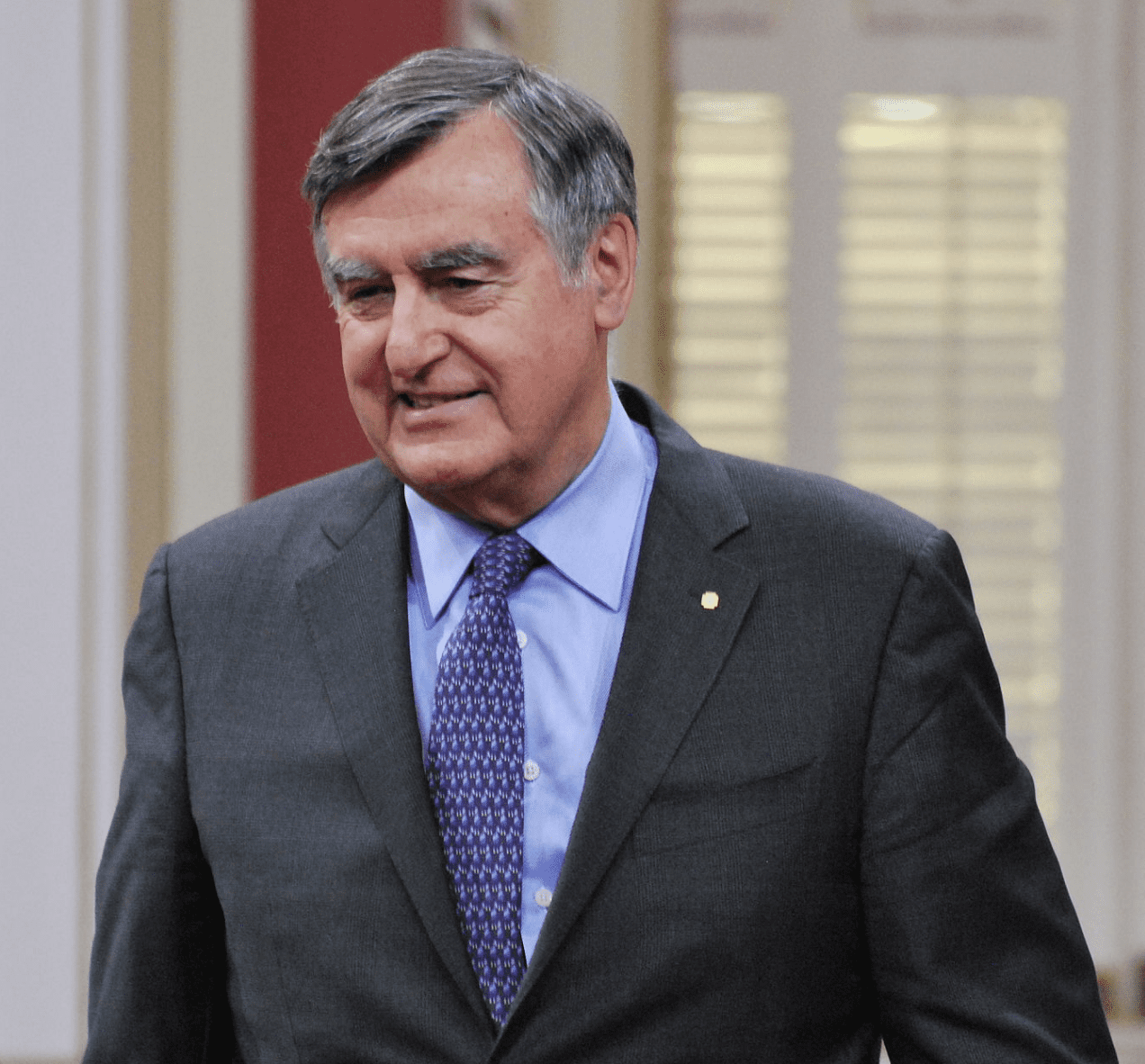

Photo Credit: CBC News