This week was not kind to leaders of the opposition in two Westminster democracies.

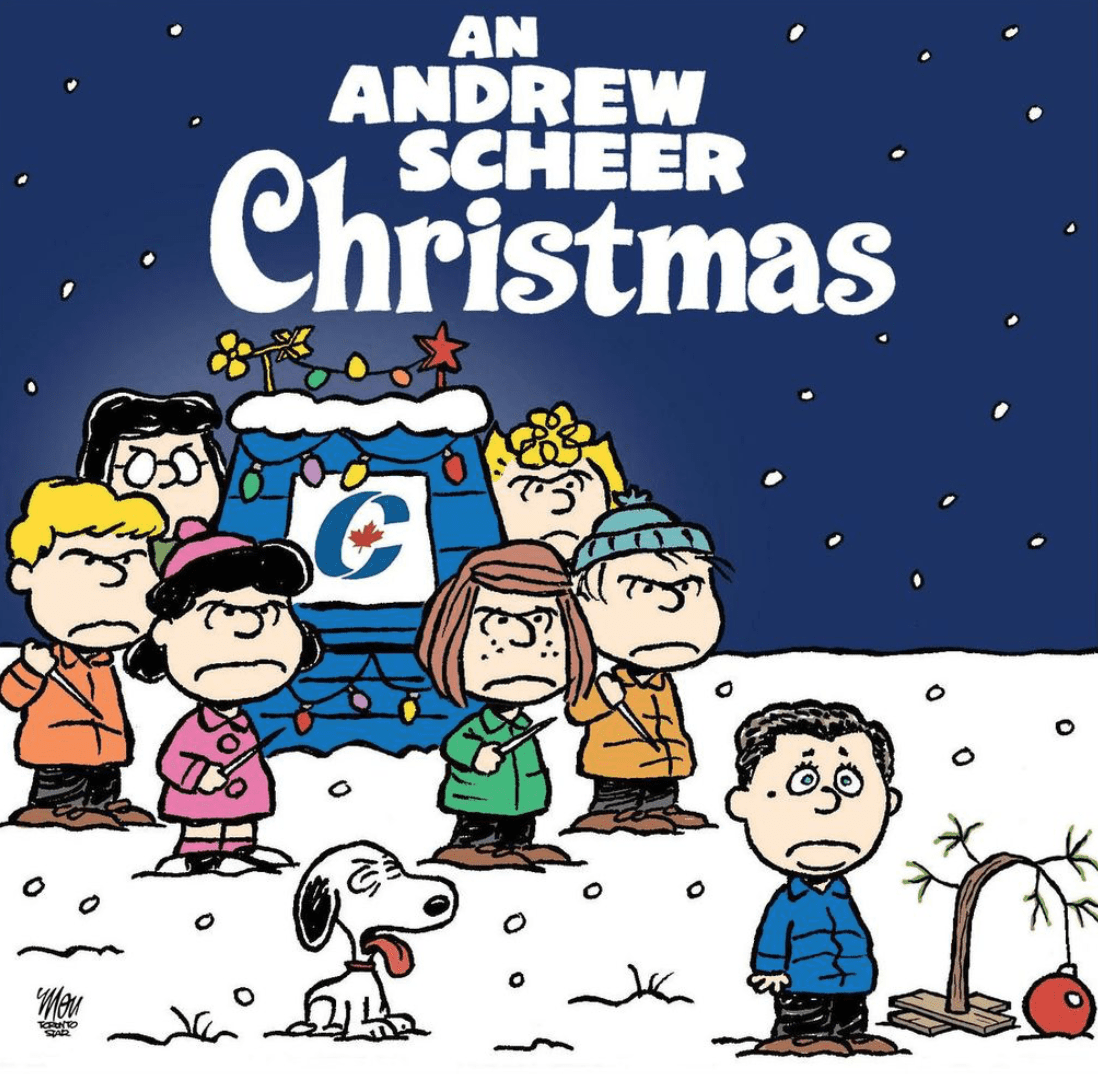

Andrew Scheer finally took the hint and fell on his sword in Ottawa after an election loss. And Jeremy Corbyn, having suffered the worst defeat for Labour since George VI, offered up his own pending resignation in London.

I did some commentary on CTV to analyse the British election results and as I waited between the 10:30pm hit and the 11:30pm hit, I read Andrew Coyne's column about Scheer's resignation. The final paragraphs stood out to me as particularly astute.

Coyne is worth quoting from at length here. He argued:

"Politics, it is said, is a battle for the centre. But what most voters mean by moderation is not ideology but temperament. You can offer the most radical program you like, within reason, so long as you look like you have thought carefully about it, could be persuaded out of it by facts and argument, and grasp the necessity of persuading others by the same means.

Radicalism is not the enemy — medicare was a radical idea, as was free trade. Extremism is. The one is about ideas, the other about temperament…

Success in politics, as in business or art, goes not to the party that simply gives people what they want, but that makes them want what it is giving them. It's not about moving to the middle, but moving the middle to you."

This argument is spot on.

Corbyn boastfully ran on a platform of radicalism: re-nationalising various institutions, slashing transit fares, providing free broadband internet, dramatically boosting social spending to fight poverty. But traditional Labour heartland voters turned their backs on him, backing one of the poshest, most establishment Tory politicians ever in Boris Johnson.

Why? I would argue it was not because of Corbyn's policies; he himself said on election night in his resignation speech, "our policies were popular". It was because voters did not trust Jeremy Corbyn, the man. It was not the radicalism of his policies but rather the extremism of his worldview, the sense that he was somehow oppositional to basic tenets of British patriotism, the sense he was too wild, too unpredictable — too "red", in the 1950s sense of that term.

Boris Johnson is likewise a radical, but he somehow managed — through a combination of religious message discipline and viral social media visuals — to come off as a good chap, someone with the courage of his convictions and a simple, clear, compelling programme, that most elusive of political elixirs. To make a Canadian equivalent, he pulled a Doug Ford: a rich guy who played a bit of the buffoon and delivered simple soundbites, repeated with clarity, no extraneous anything, thanks.

Corbyn and Scheer could not be more different. And yet the voters found them both to be wanting.

Scheer was, in his own way, branded an extremist, even if his policies and even temperament were seemingly moderate — or, to paraphrase another posh Tory Brit, Sir Winston Churchill, Scheer is "a modest man with much to be modest about". The former Tory leader came off as extreme because his worldview seemed so stubbornly out of date, and his torturous, legalese ways of addressing his opposition to equal marriage rang hollow, rehearsed and cynical.

A client remarked to me this week that "confidence" — not gold, not market reality, not even data — is the currency of the realm. That's what we look for in our leaders, too: someone who inspires confidence, trust, that they will do no harm, that they'll advance an agenda that is thoughtful. We don't mind bold ideas if they're delivered by someone competent and reassuring; we don't mind steady-as-she-goes if the leader is seen as strong and clear.

This argument seems the motivating factor behind the "Doug Ford 2.0" we're seeing at Queen's Park these days. The policy programme has hardly changed, but the Premier himself is tying to project a sense of calm authority, even graciousness when he feted his predecessor as Kathleen Wynne made history as the first female Premier memorialised with a portrait this past week.

We do not necessarily want moderate policies: bold ideas are what moves our society forward. But we do need our leaders to be moderate in their temperament, which is to say trustworthy, reliable, not too annoying.

Perhaps there's a New Year's resolution for every politician in that diagnosis.

Photo Credit: iPolitics