I'm probably breaking some sort of columnist convention but I have to concede that I'm fairly agnostic about the one-member-one-vote versus delegated-convention debate unfolding in the Ontario Liberal Party right now.

Neither system is perfect, and frankly I'd be fine with either approach being used to elect the next leader. And the right leader should be able to win, regardless of the system.

What I do object to is the impression, rightly or wrongly, that this debate is really a proxy for prospective candidates either trying to gain an advantage or protect their advantage. There is a part of me that feels strongly that we should not be writing the rules as the runners are stepping up to their starting blocks.

Indeed, the last leadership race was in 2013, and since then, there were no meaningful efforts to amend the leadership process, other than a defeated one-member-one-vote (OMOV) proposal for Ontario Young Liberal executive races.

Since then, we've seen several OMOV systems at work in other parties and places. What can we learn from these other instances?

On the positive side, the OMOV system does allow every member a chance to have equal access to the process, or at least more so than a delegated convention allows for. Everyone gets a vote through a ranked ballot. Except, that's not entirely true: you forfeit your vote if your choices become unviable on an early ballot (what's called an "expired ballot"), whereas a delegate gets to cast their vote in real time, reacting to the actual choices as they become apparent on the sequential balloting. Still, it's hard to deny that OMOV at least allows every member a chance to vote on each ballot, whereas a delegated convention allows everyone a vote to shape the first ballot, and then the smaller pool of delegates cast votes based on their own individual judgement on subsequent ballots.

Some would argue this is the virtue of the delegated convention system: every member gets to vote for a leader locally and to send delegates to the convention to vote on the subsequent ballots. In fact, some within party Facebook discussion groups have suggested the delegated process actually is a "hybrid" of OMOV and delegated, which seems to be at least technically true, if not exactly persuasive to the OMOV advocates.

In some ways, the delegated system is not dissimilar to our actual system of representative democracy, where we make our pick for a Member of Parliament based on their credentials and the party of our preference, and then that person takes future votes on our behalf. The difference, of course, is that delegates to a leadership convention are not accountable to their voters, but essentially get to vote their own conscience, interest or preference.

In both systems, the race is at first a mass mobilisation campaign to sign up as many local members as possible, often tapping into existing institutions, such as advocacy groups and ethnic communities. The difference in a delegated convention is that once the delegate-selection meetings are concluded, the focus shifts to trying to convince the smaller pool of 2000-odd delegates.

There is a certain benefit to this duality, with the leadership candidates having to court delegates one on one in the second phase; I can recall Premier Kathleen Wynne dialling up a high school student from her campaign bus between stops on a blitz of the southwest and earning the young man's support because she was the candidate who took the time to reach out. Former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney recounts an anecdote in his autobiography of being grilled over policy at a diner by one delegate, and answering her questions in detail but ultimately winning her vote because she liked the decisive way he dug his knife into a problematic kitchen bottle.

The OMOV system, however, could be argued to prioritise less of this one-on-one engagement and bypasses the same full-court press that delegated conventions require to convince members who are passionate about a particular policy or want to kick the candidates' tyres. Indeed, whether with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau or former PC Party Leader Patrick Brown, their campaigns were very notional on policy, and almost entirely focused on mobilisation.

This can lead to broad-strokes policy declarations in OMOV systems and can lead to the leader then having a hold on the party because he or she controls the membership: this is both a good and a bad thing, depending on the leader, and depending on how much of a purest you are when it comes to the Westminster system.

The one commonly cited benefit of a delegated convention is that it's just much more fun; it's pure political theatre. For a party pushed into third place, Ontario Liberals could do with the media attention of a delegated convention affords.

Ultimately, if an unscientific poll in an Ontario Liberal Facebook group is any indication, this OMOV versus delegated convention debate looks to be evenly splitting the party; the poll was tied 50-50, and constitutional amendments need a two-thirds majority.

As I continue to explore questions in the Ontario Liberal party's rebuild, I will turn to some compromise "tweaks" in my next column, outlining changes that could occur to the leadership process if the OMOV push fails to pass, because even if the system isn't replaced, it can still be improved.

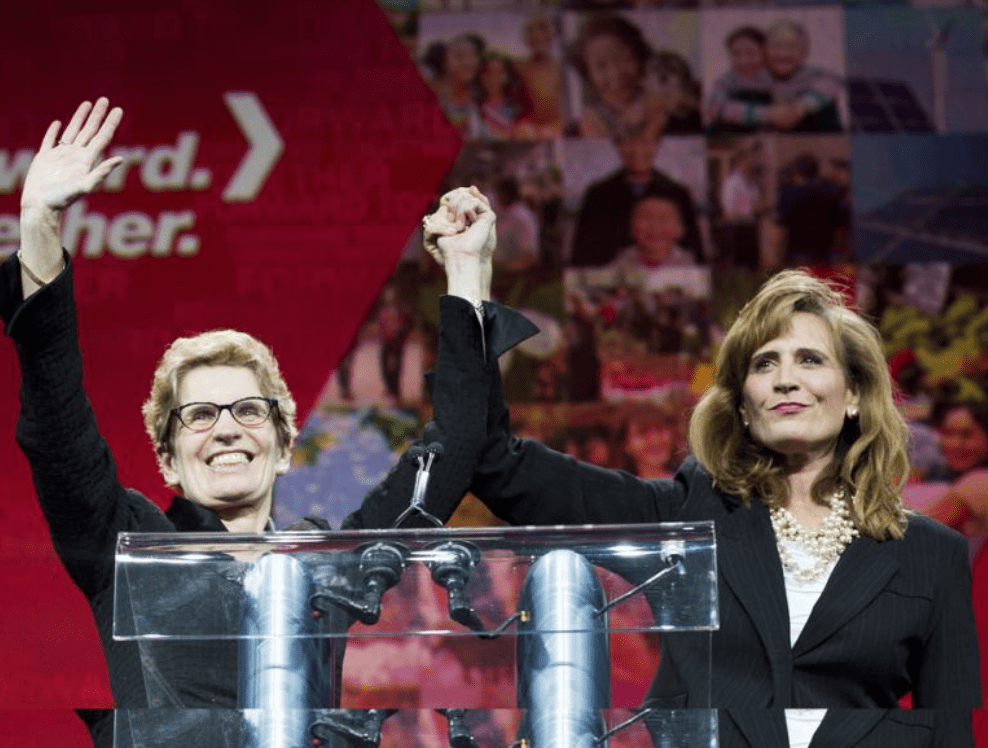

Photo Credit: National Post