This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

In political life, certain things are predictable.

Predictable things include: elections. Also: votes. And: speeches. Almost always: scandals.

Out here in the real world, there are predictable things, as well. There are too many to list.

But ever since Jesus was a little fella (literally), people have gathered to celebrate Christmas. And: Hanukkah. And: Kwanza. And: Festivus.

It’s predictable. At this time of year, people want to get together more than any other time of year. You can set your watch by it. (Again, literally.)

During a deadly global pandemic, with a Satanic variant disrupting countless lives, it’s hard to predict stuff (eg. Omicron). But people wanting to see friends and family in the month of December?

That’s as predictable as you can get. Which, ipso facto, raises one question, now being raised on many lips:

Why weren’t governments better prepared?

Because, let’s face it, they weren’t.

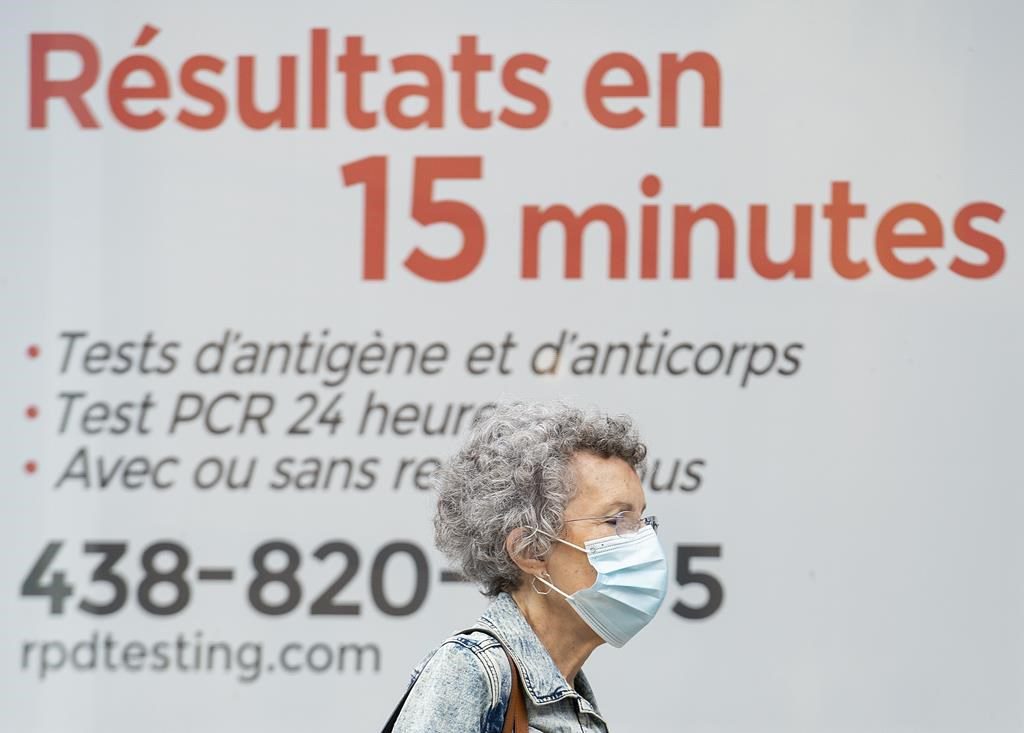

This year, Santa wasn’t being lobbied for Cabbage Patch Kids, Furbys, Tickle Me Elmos, or Nintendo entertainment systems. Nope: this year’s must-have Yuletide item was a rapid antigen test. That’s what we all wanted under the tree, this year.

But forget finding one, particularly if you live in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario or Quebec. In those provinces, rapid antigen tests – the quickie Covid 19 tests that you can do on your own – were harder to find than toilet paper in a pandemic.

It’s not like Canadian governments didn’t have them, either. The federal government claimed it had sent 80 million tests to the provinces. The provinces, meanwhile, issued lots of statements insisting that the feds had delayed or bungled distributing the tests.

Ontario, for one, said it had distributed 50 million of the tests throughout the province – including, incredibly, at liquor stores – but good luck finding anyone who actually got one. First Nations communities in Northern Ontario reported having to drive 400-plus kilometres to find a test – maybe – in far-away Thunder Bay.

Quebec witnessed massive lineups at pharmacies. In Alberta, people reported visiting multiple distribution sites, none of which had any left. Nova Scotia ran out.

In B.C., the government withheld tests, targeting places with Covid outbreaks, and wasted precious time breaking packages of tests into smaller kits. It was no surprise, then, that rapid antigen tests starting popping up on Amazon and eBay, where scumbags were charging – and getting – hundreds of dollars for tests they’d earlier obtained for free.

The Angus Reid Institute did a poll about it all, and found that two-thirds of Canadians wanted the tests free and universal. And more than a quarter of the country said they wanted to find a rapid test. But couldn’t.

Not surprisingly, about half of the poll’s respondents said their province had done a poor job distributing the tests.

(This writer’s personal favourite, however, was Manitoba: the geniuses running that province decided to distribute KN95 masks – another hot item in the 2021 holiday season – at liquor stores and casinos. Winners: slots-addicted alcoholics! Losers: Manitoba children!)

It’s right there on the calendar, Canadian political folks: December. We have an abundance of holidays in that month, when people want to – need to – get together with loved ones. And you screwed that up – with test kits, with masks, with boosters.

All of this was predictable, Canadian governments. And your failure is therefore unforgivable.

Enjoy the coal you’ll be getting in your stockings.

[Kinsella was Chief of Staff to a federal Liberal Minister of Health.]

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

Science and politics remain strange bedfellows. The ongoing uncertainty around how to fight the virus’ spread has regularly forced political decision makers to choose between politics and science.

Politicians of all stripes will have to adapt to the new normal of pandemic variants dictating major challenges to the way they govern and campaign.

For some levels of government during this crisis, the fear of being accused of paralysis of action has clearly outweighed the value of waiting for better data: others cling to the demand for scientific precision, which will never be achieved, as an excuse to court their core voters who want minimal government action.

The appearance of leadership has led policy makers in different geographies to introduce contradictory vaccine mandates and impose non-transferable passports, sweeping aside concerns about impingement on personal freedoms and choice, while delegating enforcement to often ill-equipped third parties.

Schools were open, then closed for in person learning and then reopened, as parents and kids all expressed their concerns about the limited benefit of virtual learning.

The unrelenting strain on the health care system has already left scars on both the first line heroes manning the services and the backlog of procedures that will play out in longer term negative health and cost consequences. The mental health bill is yet to be calculated but the current system does not appear to have the resources or training to manage the pandemic fallout effectively.

Governments which adopted business and individual income supports in the name of ‘covering everyone’s back’, start to phase them out only to face pressure for reinstatement as new fast spreading variants appear.

Vaccination and booster dose policies have been the subject of this tension as well. Which vaccines to recommend and purchase and distribute in a federal system, without a clear understanding of consequences or side effects was just the beginning. Further issues surround the timing of second and booster shots ( 4 weeks, 6 months , 168 days or 64 days).

Scientific study and panicked responses compete in the public mind for approval. The whiplash from instant policy change undermines confidence in government action.

Look at the introduction of travel bans, quarantining and testings regimes. It is politically soothing to announce quick action but does it make much sense if the infrastructure is not in place to administer widespread tests at airports or manage and follow up with quarantine status.

Provincial governments sit on a millions of unused vaccines and antigen tests for months, but still struggle to distribute them in an effective manner when the need arises, all the while encouraging citizens to adopt them as quickly as possible as crucial responses to COVID.

In a globalized world , in pursuit of placing the interest of our local voters first, are we reaping the consequences of not ensuring greater equity in vaccine manufacturing and distribution?

Did we learn nothing from the spread of the Black Death by trade route shipping six centuries ago?

Does it make sense to penalize countries who are forthright or honest about COVID in their midst? Or is it just safer to shut the barn door and hope for the best?

As each new COVID variant strikes, the list of challenges for governing grows longer.

We should also not minimize the significant implications for the practice of politics going forward.

In the beginning of the pandemic, governments were evaluated on the quality of their support systems for citizens and business, and for their ability to keep the public accurately informed in a rapidly changing environment. In the second phase, government’s ability to procure and distribute vaccines became ‘the rapid antigen test’.

Today, as yet another variant disrupts households and the way citizens do business, managing COVID exhaustion has become critical for the future success of different levels of government.

Government’s popularity will be measured against their latest response to the unexpected; public expectations are generally focused on future performance.

COVID’s reemergence as Government’s Job 1 will also limit political flexibility.

The federal Liberals had already given notice about cutting back on most COVID support programs; Finance Minister Freeland’s fiscal flexibility for her spring budget may be significantly constrained.

Despite ongoing efforts to deflect public attention onto inflation or the Liberals’ alleged failures in economic policies, Erin O’Toole will be faced with a media rehash of Conservative’s botched vaccination policies, and tied to provincial regimes that have been criticized for their COVID policies.

Ontario Premier Ford, whose sagging popularity has been resurrected through a strategy of remaining in the background, will once again need to play a higher profile role in managing COVID in the run up to the June 2022 provincial election.

His instinctual desire in managing the pandemic has been to loosen lockdowns and constraints, and to accommodate business wherever possible. This approach has once again been overtaken by science table demands to fight the variant, leaving him forced to contradict his stated policies. This outcome has placed Mr. Ford at odds with a significant portion of his own supporters.

How the potential of a longer lasting lockdown might affect Ontario government revenues ( various analysts have been anticipating greater revenues from a revived business sector leading to a pre-election tax cut in the spring) could change his low tax targeted spending pre-election strategy.

Alberta Premier Kenney’s ability to retain his leadership in an upcoming April review is also threatened by the emergence of Omicron after he had again deliberately loosened restrictions. He faces ongoing complaints from all sides about his government’s management of COVID.

Even though Quebec Premier Legault remains well ahead in provincial polling, the need to respond on an emergency basis to Omicron’s surge has taken away focus from his preferred scenario- using opposition to Bill 21 as an emotional strategy to secure re-election in October 2022.

Any longer term restrictive gathering policies will also impact how two key election campaigns in Ontario and Quebec can be conducted.

Omicron is casting a large shadow not only on government policy options but also on the nature of politics itself.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.