This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

Political leadership campaigns can be won and lost in a heartbeat. Watching a leadership campaign implode before it’s even started is the equivalent of flatlining in politics.

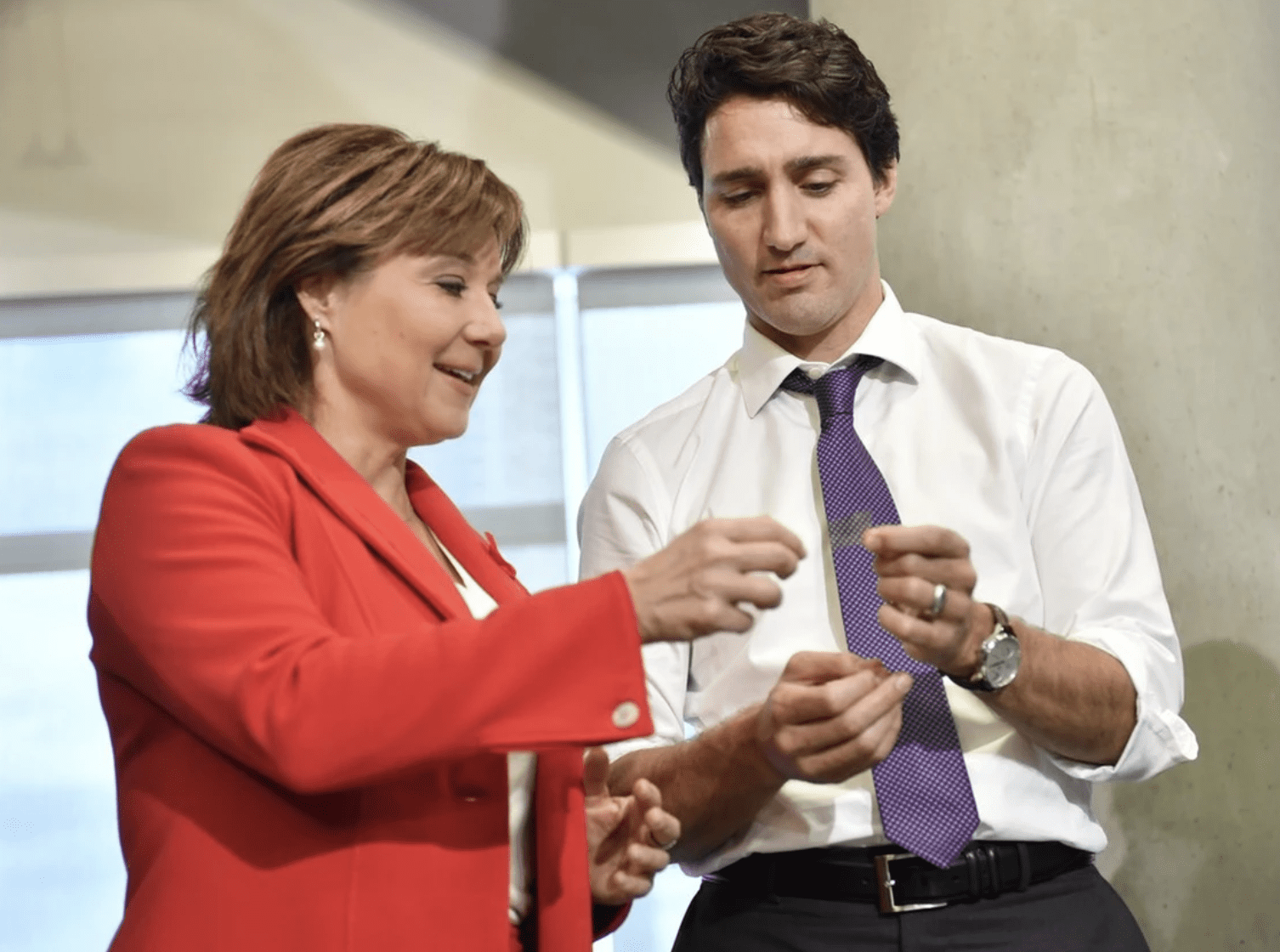

That’s what happened to former BC Premier Christy Clark. Her dreams of becoming federal Liberal leader and Prime Minister vanished into thin air in no time flat.

How did this happen?

Clark broke two cardinal rules in politics that I’ve occasionally said in private. First, don’t lie in public because you can easily get caught. Second, if you’re determined to lie, then you better know how to do it successfully. She failed in both respects, and her leadership bid was basically dead on arrival.

Let’s go back to the beginning.

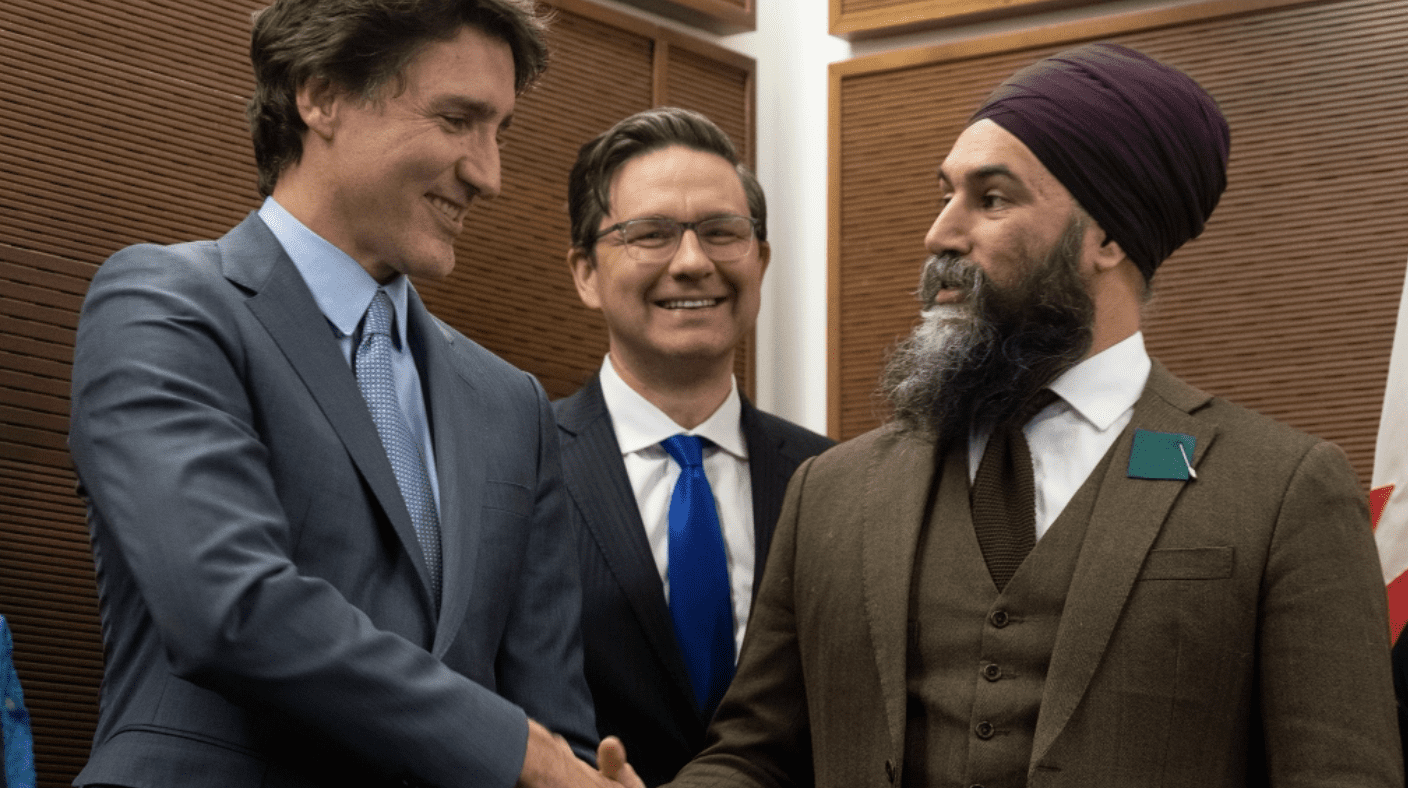

When Justin Trudeau announced on Jan. 6 that he would be resigning as Liberal leader and Prime Minister when his successor was chosen, the wheels were set in motion. Perspective leadership candidates like Chrystia Freeland and Mark Carney had to get their paperwork in order, and pay a $350,000 entrance fee, by Jan. 23. The leadership vote will conclude on Mar. 9, and the new party leader will be announced later that day.

Clark, who served as BC Premier from 2011 to 2017, was getting ready to join the race. She was viewed as a centrist Liberal, although her provincial BC Liberal Party (now BC United) is regarded as centre-right. Some federal Liberals were enthusiastic about her leadership bid, in spite of the fact that she’s never held a federal seat and doesn’t speak French. She had built a team of experienced politicos, and was perceived to be one of the main leadership candidates.

Everything came to a screeching halt after her Jan. 10 interview on CBC Radio’s The House.

Catherine Cullen, the program’s host, asked Clark this pertinent question. “You have called yourself a lifelong Liberal, but you voted in the last federal Conservative leadership race. That would have required you to cancel your Liberal Party membership in order to join the Conservative Party. How long were you a member of the Conservative Party?”

The former Premier’s response? “Never,” accompanied with a burst of laughter.

Cullen was clearly taken aback. It was not only common knowledge that Clark had endorsed Jean Charest during the 2022 Conservative leadership race, but it had been previously reported by Canadian news outlets. She had even considered running for the Conservative leadership back in 2020, lest we forget.

What on earth was she talking about?

Cullen then asked Clark, “You voted in the race, did you not?” Clark told her, “No, I didn’t. I didn’t. And I never got a membership, and I never got a ballot. What I did, though, is…” which led Cullen to interrupt and say, “We reached out to the Conservative Party, who told us, in fact, that your membership was cancelled.”

The stunned look on Clark’s face spoke volumes. “Oh, well, why don’t they show, come out and show my membership or my ballot? They never sent me any of those, although I wouldn’t put it past them to manufacture one of them.”

Within hours, everything that Clark said and insinuated had fallen apart.

“Christy Clark purchased a Conservative Party membership through Jean Charest’s leadership campaign,” Conservative communications director Sarah Fischer wrote in an email to the CBC. “That membership is no longer active.” A screenshot of Clark’s Conservative membership in the riding of Vancouver Centre from June 2, 2022 to June 30, 2023 was posted on social media by longtime Conservative activist and political advisor Jenni Byrne.

The CBC also posted a damning video clip of an Aug. 21, 2022 interview that Clark conducted with the Conservative Journal of Canada. She specifically said, “I’m joining the party so I can support Mr. Charest and what I think he can bring to the national dialogue.”

An interview between Cullen and CBC’s Power and Politics host David Cochrane put the final dagger in Clark’s leadership bid.

“She went on to say in the interview that she called the Conservative Party numerous times to ask where her ballot was,” Cullen told Cochrane. “And I said, well, wouldn’t you have to be a member in order to expect a ballot from them?” Cullen continued, “I asked if she cancelled her Liberal Party membership. She said no. Her team now says that she was, in fact, not a registered Liberal when she supported Jean Charest.”

Canada’s political and media chattering classes were completely dumbfounded. How could an experienced politician like Clark have left herself wide open to this type of criticism? What a mess.

Clark then sheepishly posted this to her X account later that evening, “Well, I misspoke. Sh*t happens. Lesson learned…”

Sorry, “misspoke?” No, Clark had lied through her teeth and couldn’t cover her tracks.

It didn’t make sense why she had done this. All Clark had to do was explain to Cullen that she had briefly been a Conservative Party member and voted for Charest. She didn’t support Pierre Poilievre, the newly elected Conservative leader, and let her membership lapse after one year. She then returned to the Liberal fold, where she’s been ever since.

How hard was this to say? It wouldn’t have been held against her. Some of her fellow Liberals have belonged to different parties and shifted their political allegiances. Conservatives, New Democrats, Greens and others have done this in the past, too.

Yet, her first inclination was to concoct a lie that quickly unravelled. She suggested the Conservatives would “manufacture” her party membership when, in fact, they had all the real evidence and documentation they needed at their fingertips. She disappointed her political team. She lost the trust of Liberal MPs and supporters. She ruined her public image. She destroyed her leadership bid before it had even started.

When Clark announced on Jan. 14 that she wasn’t going to run, no-one was surprised. What were her reasons for making the “difficult decision to step back?” The timing to organize a successful campaign wasn’t favourable, and there was “simply not enough time…to effectively connect with Francophone Canadians in their language.”

Putting those two roadblocks aside, let’s be honest. Clark isn’t running for one reason: the lie that imploded her leadership campaign and potentially destroyed her political career for good. If that’s not an example of flatlining in politics, I don’t know what is.

Michael Taube, a long-time newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

Become a subscriber today!

Register

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.