We’ve been hearing and seeing slow responses to federal appointments for a while now, whether it’s been around the slow pace of judicial appointments that had the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada reaching out to the prime minister to make a plea to faster action, or if it’s been the neglect of filling seats in the Senate that has reached Harper-esque levels. It turns out that the problem is much worse and more widespread across all federal Governor-in-Council appointments—that nearly one quarter of those positions are either vacant, or are staffed by members who are beyond the expiration of their terms and who are on some kind of extension. This is very, very bad for the governance of our country.

With some of these positions, there is a demonstrably false narrative circulating that Trudeau has been refusing to make appointments, such as with the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner. In that particular case, and only that particular case, the problem is not the government, but rather the Parliament of Canada Act which specifies that such a position must be held by someone who is either a former judge or head of a tribunal, board or commission, and though it’s not in the legislation, they would also need to be bilingual. The problem there is that MPs (and the blame lies principally with the Conservatives and former NDP MP Pat Martin) who wrote these requirements as part of the Federal Accountability Act back in 2006 made that qualification so restrictive in a fit of moral superiority they believed that they would attract the “best of the best” to this position. What happened instead is that because they made it too narrow, they created a situation where the people they had in mind for the job would have no interest in it. There was a reason why the first Commissioner under this regime, Mary Dawson, had to have her term extended several times, and the fact that Mario Dion was pretty much the only choice to replace her, as there were really no other applicants.

This particular appointment aside, there are a few problems with how this government has been operating when it comes to its constitutional obligations to make these appointments. On the operational side, they have lacked the general bandwidth and capacity to deal with these issues as a result of a combined lack of attention by several of the ministers involved, as well as their key staff, and this gets compounded by the bottlenecking that happens within PMO when these decisions go for approval. The figures that the CBC compiled have shown some wild disparities between departments when it comes to the number of vacancies, with Transport Canada being among the worst (where the appointments are around positions like board members for port authorities), while Employment had one of the lowest rates (with appointments to bodies like the Social Services Tribunal). Knowing the ministers involved, this isn’t a surprise—Omar Alghabra was more focused on the political ramifications of his files and how to leverage those, while Carla Qualtrough is a no-nonsense minister who can manage complex files and communicate with frank effectiveness.

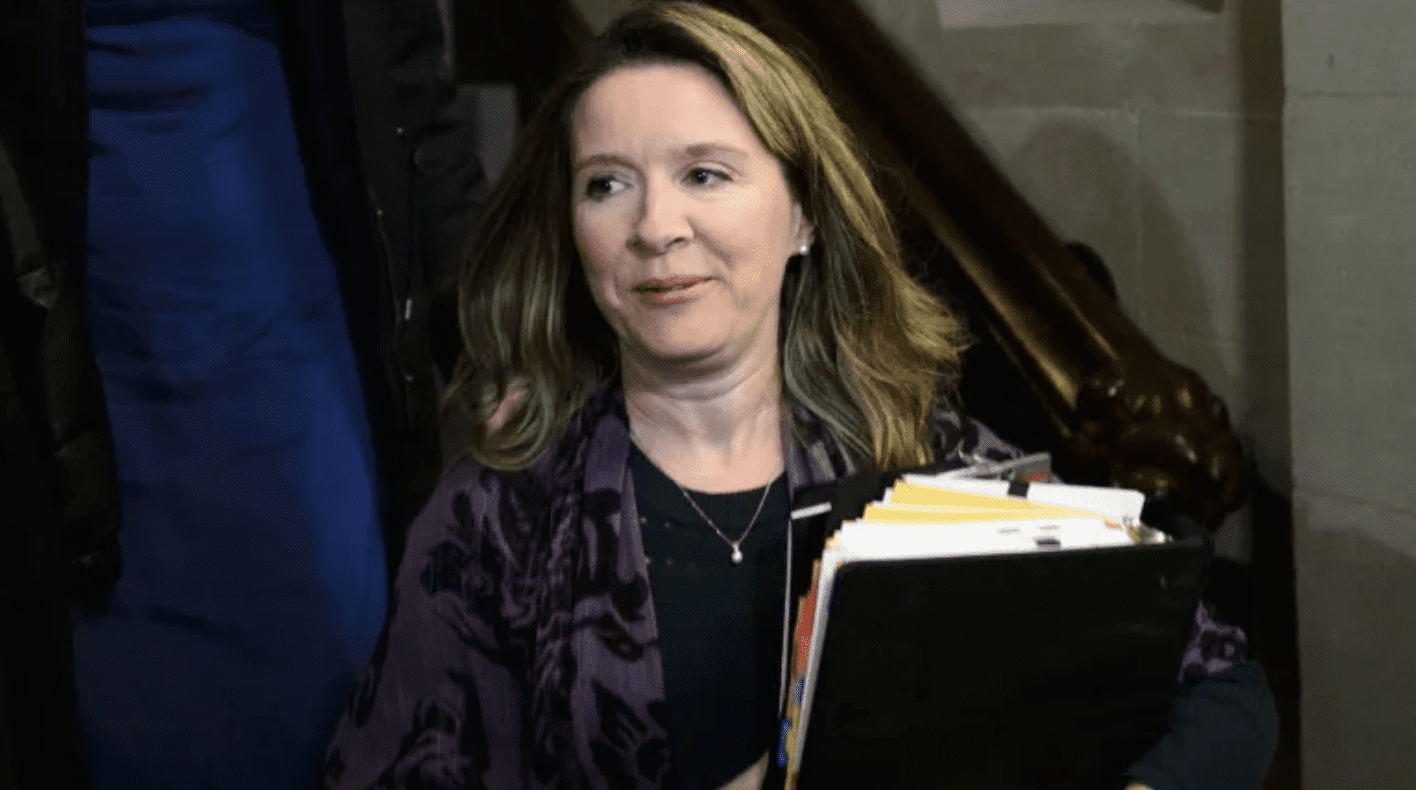

The bottlenecking in PMO is a known problem that the prime minister refuses to do anything about, because he won’t expand the circle of trust when it comes to signing off on decisions. That means that virtually everything funnels through to his chief of staff, Katie Telford, and her deputies, and none of them want to relinquish any of their power, even when we can see that the concentration of that power leads to decisions being delayed until the last minute, an inability to plan or get ahead of issues, and the kind of problems that are seen here with this lack of action on key appointments that should be made. It’s a problem which the Auditor General has been calling out for years and which they still haven’t managed to speed up or solve.

Outside of the operational problems are the cultural ones within this government, and that has to do with their desire to make more diverse appointments across the board. This is a good thing overall—there is no shortage of studies that prove that more diverse decision-makers leads to reduced risk and better outcomes, whether in the corporate board room or in a myriad of other situations. The problem is that this government hasn’t paid attention to their own rhetoric about issues like systemic racism or structural biases against gender, ethnicity, disability, or any other kind of diversity. As much as this government likes to pay lip service to things like Gender-Based Analysis-Plus, which should mean that they take an intersectional look at the problems they are trying to solve, their usual pattern is to simply mention the words, but not do the work behind it. These appointments are little different.

Because this government is committed to conducting its appointments by self-nomination (meaning people need to apply instead of being sought out), they have put almost no effort into ensuring that the kinds of diverse talent that they want to apply will actually do so. This government seems to think that by simply saying “Hey, we’re appointing diverse candidates!” that all kinds of women, people of colour and LGBTQ+ candidates will rush to apply, and that there will be such a glut that they will have to fight them off. That’s not the case, and when they get a bunch of applications by middle-aged straight white guys and very few from anyone else, they still haven’t stopped to consider how to change their approach to better attract those candidates. Hell, even as a party, the Liberals got the memo that women and minorities need to be asked several times before they would even consider running for a nomination—so why can’t they do that for these federal appointments? It boggles the mind that they have stubbornly refused to put two-and-two together.

While the government told the CBC that of course they plan to fill all of these vacancies, this is one more area where their deliverology is failing them. They need to take this seriously; they need to change up their strategy and actually start sending people into the field and actually nominating people to these positions rather than waiting for applications that will never come. They need to act like grown-ups with eight years of government experience in hand, rather than continuing with these amateur-hour shenanigans that corroding their brand, and their legacy.