Have you ever wondered what it would be like to speak with a historical figure?

Imagine the conversations you could have had with philosophers like Plato and Socrates. Military leaders like Julius Caesar and Sun Tzu. Musicians like Ludwig von Beethoven and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Political leaders like Abraham Lincoln and Sir John A. Macdonald.

While these opportunities will obviously never materialize, there are now unique ways to engage (sort of) with figures from the past. Modern technological advances in artificial intelligence, or AI, allow us to “speak” with famous people who left their mark in some way, shape or form.

A word of warning. If you have unusually high expectations about the potential content, flow and accuracy of these conversations, you’ll be a bit disappointed.

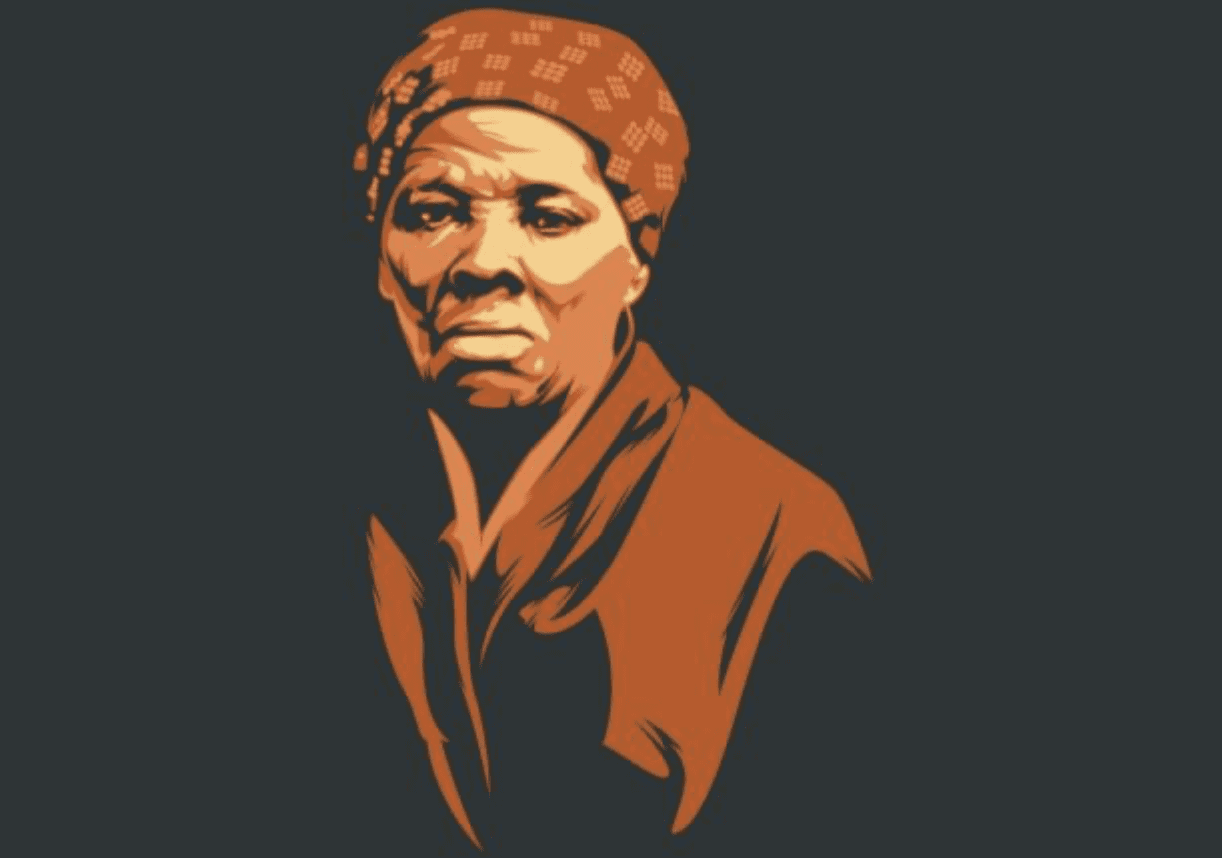

Here’s an example. The Washington Post’s Gillian Brockell conducted an “interview” of July 16 with an AI simulation of Harriet Tubman. That’s the well-known U.S. abolitionist leader who escaped slavery on Sept. 17, 1849, and made 13 missions over an eight year period to help rescue roughly 70 enslaved people. She used the secret network of routes and safe houses known as the Underground Railroad, and never got caught under this cloak of darkness.

Tubman also served as an armed scout and spy for the Union Army during the American Civil War. She strongly supported the women’s suffrage movement, too.

Brockell used Khan Academy’s artificial intelligence learning tool, Khanmigo, for this interview. The nonprofit online educator launched the Chat4 system earlier this year that “enables users to have live chats with dozens of simulated historical figures like Abigail Adams, Genghis Khan, Montezuma and Winston Churchill.” She, like anyone in her position, didn’t exactly know how this discussion would go. “Would the AI attempt Tubman’s authentic speech, her religiosity, her tenacity?,” Brockell wondered. “And if so, would it come off horribly, a 21st-century minstrelsy? Or would it be like ‘talking’ to a Wikipedia entry?”

It turned out to be a mixed bag.

“I was relieved to find the Tubman simulation using modern conversational language, though still infused with hints of her courage and piety,” Brockell wrote. “I was surprised to find ‘her’ asking me questions, too, and that a small part of me wanted to give sincere answers.” At the same time, she noted that “it was difficult for the bot to say much more than the superficial things most of us learned about her in high school, and ‘she’ failed some of The Washington Post’s accuracy tests.”

There are several instances of historical inaccuracies in the Brockell-Tubman interview.

She asked Tubman at one point, “Did you say ‘I freed a thousand slaves. I could have freed a thousand more, if only they knew they were slaves?’” The AI simulation of the prominent abolitionist answered it thusly, “Yes, that quote is often attributed to me, although the exact wording may vary. The sentiment behind it is that many enslaved people were not aware of the true extent of their oppression or the possibility of a better life. It was difficult to help those who did not recognize the need for change or who were too afraid to take the risk.”

Aye, there’s the rub.

“Tubman did not say this, despite what Kanye West and various memes claim, and there are many articles online saying so,” Brockell correctly noted. “I was disappointed that the AI evidently wasn’t able to discern quality of information.” When she asked Sal Khan, the Academy’s founder and CEO, about this discrepancy, he said “the bot isn’t a fact-checking tool and noted ‘Tubman’s’ hedge in ‘her’ response, that the quote ‘is often attributed to me.’” He suggested this is an “improvement in the technology,” and there should be more improvements in about six months.

Brockell was unable to get responses about modern issues and controversies, either. Tubman wasn’t able to answer why her image still isn’t on the $20 bill (“The decision to feature me on the $20 bill is a modern development, and I cannot speculate on current events or decisions”) or express an opinion about reparations for slavery (“The concept of reparations for slavery was not widely discussed during my lifetime, and my primary focus was on helping enslaved people escape to freedom and advocating for the abolition of slavery”). Brockell was particularly “disappointed with the hedge and the vagueness” for the latter response, since reparations were discussed to some extent in Tubman’s time.

In fairness, Brockell’s expectations for this interview seemed way too high. Existing AI tools aren’t perfect. Only certain aspects of an individual’s life, career and thoughts can be properly recreated through this technology. Chronological and historical mistakes will occur, and hopefully diminish as things improve.

Most importantly, this isn’t the real Harriet Tubman. A human being with a range of emotions and personal memories would have likely answered these questions very differently than the AI simulation. She also might have tackled some modern topics like reparations for slavery and critical race theory, using historical themes and context to mask her obvious deficiencies and lack of understanding of these hot button issues.

Nevertheless, I believe this should be regarded as a successful experiment with a new, emerging technology. It may even reach the point one day where the real person and AI simulation are neither separate nor different, but remarkably close to being one and the same.

Michael Taube, a long-time newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.