Political parties and leaders have taken people for quite a ride lately. The Chinese election interference controversy in Canada, which has thrown Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the Liberals for a loop. Former U.S. President Donald Trump’s rumoured arrest due to hush money payments to porn star Stormy Daniels. French President Emmanuel Macron survived a no-confidence vote after raising the retirement age from 62 to 64 years.

One of the more interesting political stories that didn’t catch quite as many eyeballs as the others happened in the Netherlands.

The Farmer-Citizen Movement, also known by the acronym BBB, came completely out of nowhere to win the Dutch provincial elections. The four-year-old agrarian protest party won 138 of 572 seats in the 12 provinces, well ahead of the centre-right People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), which finished with 63 seats.

Depicted as the “new powerhouse of Dutch right-wing populism” by AP News, the Farmer-Citizen Movement was predicted to win up to 15 seats in the 75-seat Dutch Senate. (The twelve provinces vote in the upper house members.) Based on new estimates, the number will likely reach 17.

“People, what the fuck happened?,” BBB party leader Caroline van der Plas said in her victory speech. While the line was obviously a bit crude, the sentiment is probably what most seasoned political observers were thinking. “This isn’t normal, but actually it is!,” she went on to say. “It’s all normal citizens who voted.”

How did this happen? The genesis goes back to the Dutch farmers’ protests.

Prime Minister Mark Rutte and his VVD government had proposed a plan in 2019 to cut the country’s livestock by 50 percent and reduce agricultural pollution. The increase of environmental awareness in the Netherlands, a nitrogen emission crisis and the Party for the Animals and GroenLinks winning seats changed the political dynamic. The PM devised a strategy to counter their newfound voice and potential electoral growth and take back control of the narrative for environmental issues.

Farmers, in turn, felt they were either being ignored, pushed aside or put out to pasture by politicians and their countrymen. Their livelihoods were going to be slashed for political gain. They could lose their farms. They were furious, and understandably so.

“Over the past 20 years, the agricultural sector has moved back and forth along with the rules imposed by politicians,” Eddy van Wezel, a farmer from Huijbergen, told Politico in an Oct. 16, 2019 piece. “Now farmers are forced to bear the brunt of emergency measures to combat nitrogen emissions.”

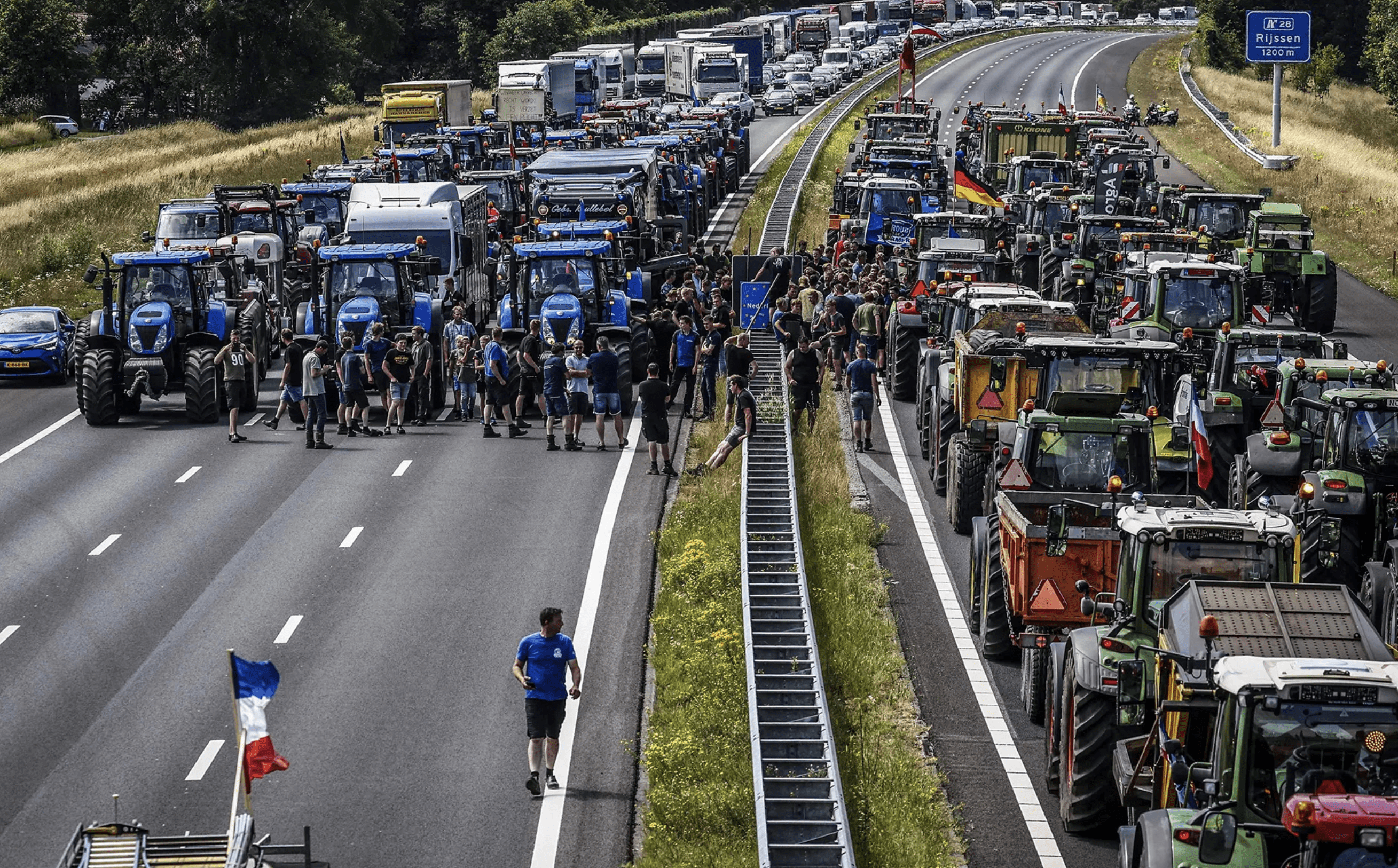

That’s why van Wezel and his son drove their tractor to The Hague to join other farmers in a nationwide protest. Hours-long traffic jams and demonstrations occurred at the legislative capital that day. Farmers also went to Utrecht, where a government environmental institute, ANWB, is situated that they believed was “responsible for publishing misinformation about nitrogen emissions,” according to al-Jazeera and other news organizations.

The farmers’ protests didn’t end in 2019. They’re still ongoing. It’s involved everyone from average citizens to political leaders. Demonstrations at The Hague are commonplace. Protests have also been held in Maastricht (2020), Assen and Arnhem (2021), the village of Stroe, Gelderland (2022) and Nijmegen (2023).

Support for the Dutch farmers has occurred in several countries, including Canada. Politicians like Trump, France’s National Rally leader Marine Le Pen and Poland’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Agriculture Henryk Kowalczyk have all spoken out in favour of the protests, too.

Van der Plas, along with Wim Groot Koerkamp and Henk Vermeer from the agricultural marketing firm ReMarkAble, formed the Farmer-Citizen Movement on Oct. 1, 2019. The theory was to feed off of the populist success of the farmers’ protests. She’s an agricultural journalist who wrote on the meat industry for Reed Business and provided communications strategies for the Dutch Association of Pig Farmers. She was unanimously elected party leader on Oct. 17, 2020, and led them during the March 2021 general election.

BBB ran on a pledge for a “Ministry of the Countryside” located at least 100 kilometers from The Hague, and a Right to Agriculture Act to give farmers a seat at the table with respect to expansion plans for Dutch agriculture. They support Dutch membership in the EU solely for trade and commerce, as well as Dutch membership in NATO.

The party ended up winning one seat in the House of Representatives. Van der Plas has been a member of parliament ever since.

To believe that one House seat could turn into 138 provincial seats and 17 Senate seats in two years is remarkable.

“The BBB has tapped into populist sentiments,” Deutsche Welle noted on March 16, “and resentment toward mainstream politics, appealing to voters who felt ignored by Rutte’s government.” The BBC also suggested on March 16 that the party’s appeal “has spread rapidly beyond its rural heartland, on a populist platform that represents traditional, conservative Dutch social and moral values.”

Indeed, the Farmer-Citizen Movement is part of a wave that’s encompassed populism and protest on the political right and left. This includes Trump’s presidency, Macron’s leadership in France, Brexit in the UK, Italy’s Five Star Movement and even U.S. Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders. It’s had ebbs and flows, to be sure, but isn’t going away anytime soon.

Some political rides last longer than others, it seems.

Michael Taube, a long-time newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.