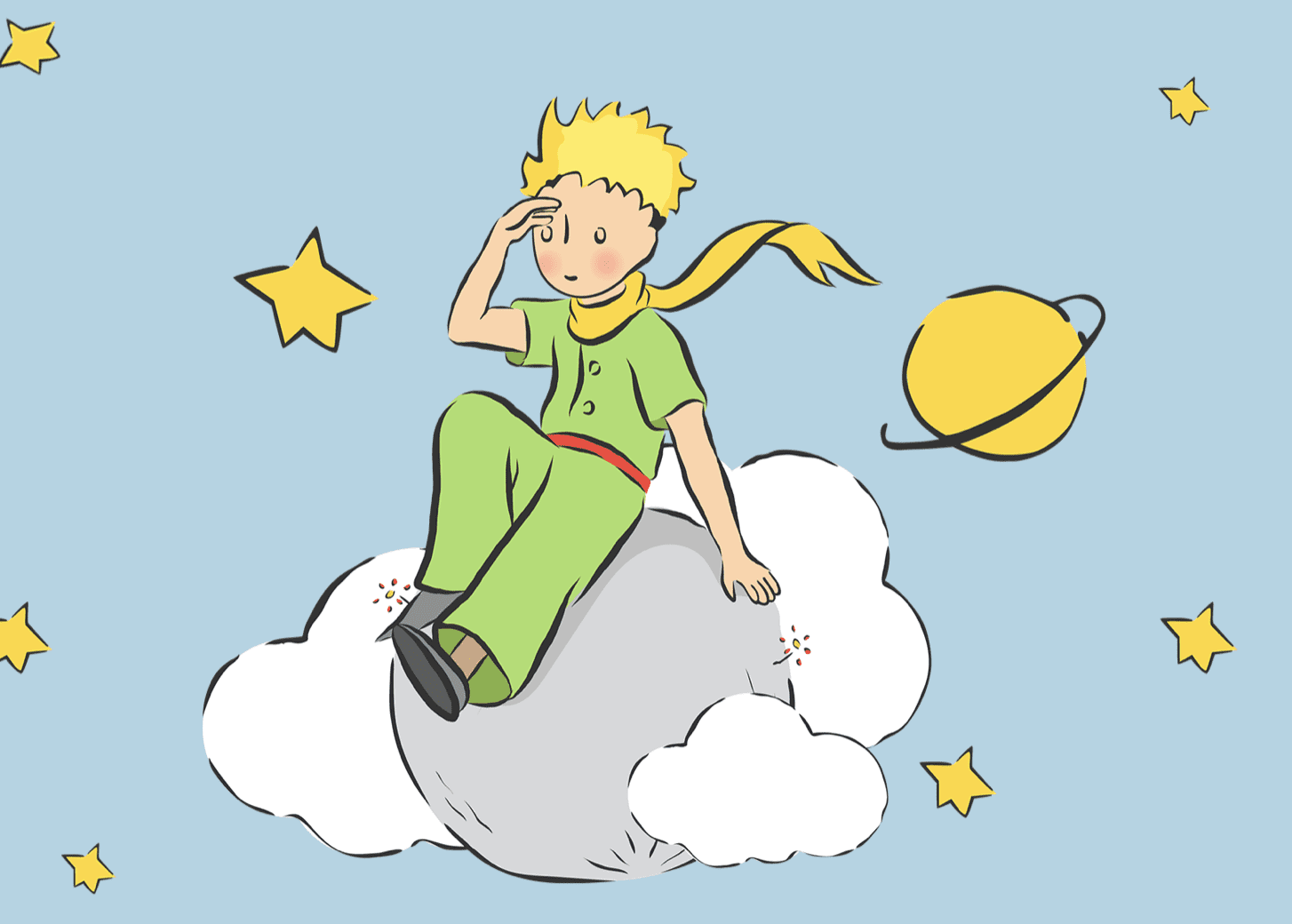

I happened to recently come across a memorable quote from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince (1943). It’s in the preamble dedicated to Léon Werth, a fellow writer and friend, and includes this line, “All grown-ups were children once – although few of them remember it.”

This classic tale of children’s literature resides on one of my bookshelves. It’s been years since I read it. So, I decided to immerse myself in the little prince’s intergalactic adventures. He witnesses vivid differences in the human condition, especially in terms of how children and adults see our world and what matters most to them.

Saint-Exupéry never lived to see the book’s success. A commercial pilot who joined the French Air Force and opposed Nazi Germany, he disappeared in July 1944 on a reconnaissance mission. His silver identity bracelet was found in 1998 by a fisherman to the east of Riou Island. Remnants of his plane were discovered and identified in 2004.

He would have been pleased to know that Le Petit Prince became a tao of children’s literature. That is, “the way” (according to Mandarin Chinese) or the path to life, existence and understanding the universe. If you read his book, you’ll learn something important and hopefully retain it for the rest of your life.

Not every children’s book has achieved, or will ever achieve, the status of tao.

Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1901), A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon (1947), Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955), Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat (1957), Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach (1961), Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day (1962) and Maurice Senadak’s Where the Wild Things Are (1963) deserve to be in this category, among others. While it’s difficult to duplicate these masterful volumes in our modern society, several examples include Sam McBratney’s Guess How Much I Love You(1994), Julia Donaldson’s The Gruffalo (1999) and Mo Willems’ Knuffle Bunny (2004).

Determining what constitutes great children’s literature depends on the times you lived in, the books you were exposed to – and the words that evoke powerful memories. Jean de Brunhoff’s Babar the Elephant (1931), Virginia Lee Burton’s Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel (1939), Margret Rey and H.A. Rey’s Curious George (1941), Tibor Gergely’s Scuffy the Tugboat (1946) and Richard Scarry’s Best Word Book Ever (1963) always fill me with fondness and pleasure. Others can do it with Dav Pilkey’s Captain Underpants series, Aaron Blabey’s The Bad Guys and Todd H. Doodler’s Super Fly. Can I explain this fascination with the latter volumes? No. To each their own, I guess.

Here’s the second part of my story.

Less than two weeks ago, I drove past a house in my neighbourhood that had put out some books for free. The vast majority of offerings were classic children’s literature that I had read at home and in the library when I was young.

Hildegarde H. Swift’s The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge (1942), for instance. It’s the magnificent tale of a small red lighthouse that resides in Fort Washington Park in New York City next to a large gray bridge. When a thick fog comes rolling through the Hudson River, the bridge asks the lighthouse to shine its light to guide the ships. Surprised, he asks why. “You are still master of the river,” the bridge tells his friend. “Quick, let your light shine again. Each to his own place, little brother!” Even the small can be mighty, indeed.

Marcia Brown’s Skipper John’s Cook (1951) was one of my favourites. It’s about a young boy, Si, who becomes a cook on his friend Skipper John’s ship, the Liberty Belle. His first meal was fried fish and potatoes. “Fine grub, Si,” the fishermen said. There was more fried fish to come. Sensing the crew had had their fill with ocean treasure, Skipper John asked Si what else he could cook. He replied, “Beans, Sir. Fish and – beans.” The trip was a success. The “best fish fryer I ever saw” went home to his mother, and the good Captain looked for a new cook who would serve something other than fish to eat.

There was also Norman Bridwell’s The Witch Next Door (1964). Author of the beloved Clifford the Big Red Dog books, this is an equally memorable tale. A witch moves next door to two young children. She paints her house black, takes her unusual pets for a walk, uses a magic broom that “keeps her house very neat” – and if “someone is sick, she sends them cookies and hot soup.” Some neighbours weren’t crazy about having a witch next door. She’ll show them – in the most amusing way possible!

Finally, there was Russell Hoban’s Egg Thoughts and Other Frances Songs (1972). He wrote wonderful stories like Emmet Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas and The Mouse and His Child. This volume collects songs and rhymes from his Frances the Badger series. “I do not like the way you slide/I do not like your soft inside/I do not like you lots of ways/And I could do for many days/Without a soft-boiled egg.” Egg-xactly, I say! There’s also a ditty about Noah’s lost ark (“Mister Noah in your ark/Lost and lonesome in the dark/Are the animals all right?/Do you tuck them in at night?/Will I ever find you?”) and summer (“Summer took, summer took/All the lessons in my book/Blew them far away/I forgot the things I knew/Arithmetic and spelling too/Never thought about them.”)

Ah, what a wonderful trip down memory lane! The first two books are now part of my permanent collection. The other two will be donated to a Little Free Library for young children to enjoy.

“The world that children occupy does not always look to them as it does to us,” children’s book reviewer Meghan Cox Gurdon wrote in the Wall Street Journal on Feb. 11. “Where we see an open basement door, they may see a hungry mouth. What look to us like flower petals may look to them like the skirts of a fairy.”

Very true. It’s through their eyes and vivid imaginations that we can see and experience our world in a different light. It’s also through their books that we can smile, pretend and believe that anything is possible.

“Grown-ups are very strange,” Saint-Exupéry’s little prince says on one of his magical adventures. Sadly, he may be right.

Michael Taube, a long-time newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.