Imagine if Chrystia Freeland’s tweet about Erin O’Toole’s health-care policies had been vetted by a layer of government bureaucracy.

For those who been enjoying the summer rather than obsessing over political shenanigans, Freeland tweeted a video of O’Toole seemingly embracing the idea of private health care. But the clip cut the part where O’Toole said universal access is paramount. Twitter flagged Freeland’s tweet as “manipulated media.”

Now imagine if bureaucrats had to make a ruling on Freeland’s tweet.

Should they side with the government that appointed them? Or should they side with someone who might be their boss in a month?

While these questions may seem abstract now, the federal government’s internet censorship agenda could make these questions much more real in short order.

For months, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has been trying to convince Canadians that we desperately need government bureaucrats to regulate, filter and block online content that might be seen as harmful.

But Freeland’s tweet lays bare the ever-true reality of politics: governments have a poor track record when it comes to telling Canadians the truth. How can we trust bureaucrats appointed by government to become neutral arbiters of truth? The fact is, we can’t.

Canadians are smart. We know that politicians don’t always tell the truth. We can tell when words are taken out of context. No government adjudication is necessary.

Yet, earlier this year, the Trudeau government introduced Bill C-10. The legislation sought to give massive new powers to government bureaucrats to put Canadians’ online content under the microscope.

Under the guise of promoting Canadian content, unelected regulators at the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission would have been given the power to monitor what Canadians watch and share online and ensure it conforms to government approved standards.

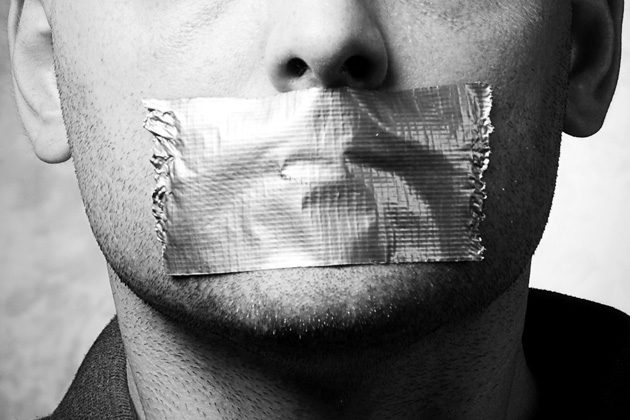

This attack on free speech is unprecedented.

“Regulating user generated content in this manner is entirely unworkable, a risk to net neutrality, and a threat to freedom of expression,” said University of Ottawa Law Professor Michael Geist.

The government also released a proposal for a so-called online harms bill earlier this summer, which would take government censorship a step further.

The Trudeau government’s rationale for introducing this sweeping new legislation was supposedly to guard against online harms like hate speech and child pornography, but these evils have already been illegal under the criminal code for decades.

The government’s proposal would create a new Digital Safety Commission, led by a Commissioner chosen by cabinet, and a new tribunal, whose members would be chosen by the minister of heritage.

Collectively, the Commissioner and the tribunal would be empowered to recommend and ultimately block online content that they deem to be harmful.

Given that all of the powerful actors would be appointed by politicians, there is a clear risk that the very partisans that appoint these bureaucrats might be able to influence what should or should not be removed online.

While the targeted content might be online harms today, what’s to stop the government from expanding the parameters of those bureaucrats’ powers tomorrow?

The combination of Bill C-10 and the online harms legislation sets the stage for significant government influence over what Canadians can watch, see and share. And these powers could easily be expanded in the future.

Freeland’s tweet has unintentionally shown Canadians exactly why government bureaucrats should not become Canada’s new arbiters of truth.

When it comes to freedom of expression, Canadians, not government bureaucrats, should be put in the driver’s seat.

Jay Goldberg is the Interim Ontario Director at the Canadian Taxpayers Federation