This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

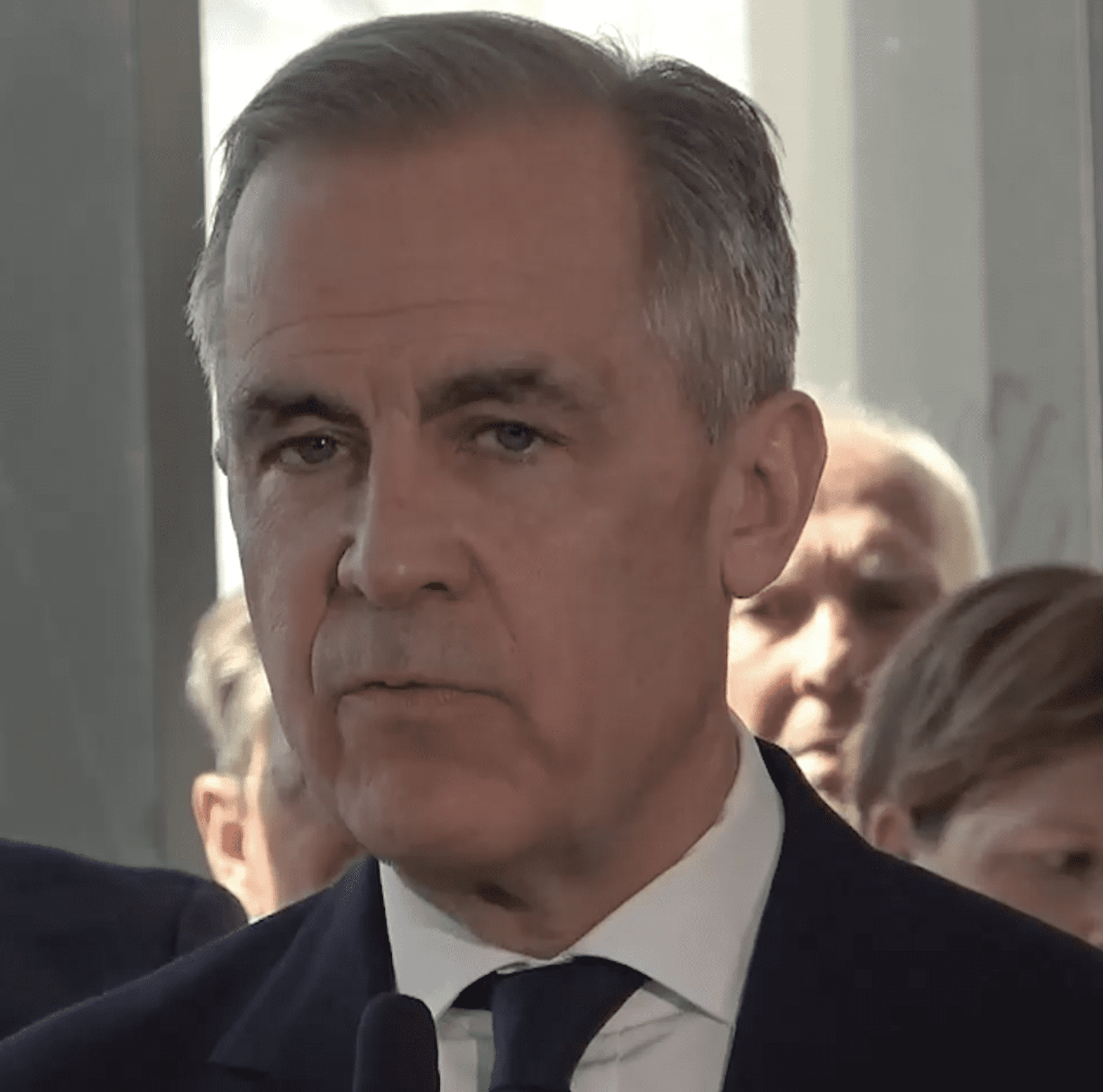

What is Prime Minister Mark Carney’s relationship with China? Opinion and analysis has been varied, ranging from mild concern and bemusement to offensive remarks and conspiratorial thinking. Whatever the relationship entails, one thing seems clear: Carney and the Liberals can’t escape the shadow of the Chinese Communist Party.

This was highlighted during the Paul Chiang controversy.

During a January news conference with Chinese-language media, it was revealed that Chiang, a retired 28-year police veteran and one-term Liberal MP, had disgracefully encouraged Canadians to collect a $183,000 bounty placed on Conservative candidate Joe Tay’s head. The Ming Pao newspaper reported that Chiang said it would be a “great controversy” if Tay, running in a different riding, was elected and “if you can take him to the Chinese Consulate General in Toronto, you can get the million-dollar reward.” It was a disgusting and reprehensible comment by Chiang, who tried to dismiss it as a bad joke.

Carney refused to remove Chiang as a candidate. While claiming to be “deeply offended” by Chiang’s comments, the PM had the audacity to call it a “teachable moment.” It was a phrase straight out of former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s decrepit political playbook. “He’s made his apology,” Carney said. “He’s made it to the public, he’s made it to the individual concerned, he’s made it directly to me, and he’s going to continue with his candidacy. He has my confidence.” The controversy inexplicably continued for another 24 hours until Chiang finally resigned.

One would have thought the Carney Liberals would have found a replacement for Chiang with as clean a record as possible. Then again, maybe not.

Peter Yuen, Toronto’s former deputy chief of police, was selected as the new Liberal candidate in the riding of Markham–Unionville. He found himself in hot water almost immediately. He’s reportedly a “member of a Beijing-friendly lobby organization,” according to the Globe and Mail’s Robert Fife and Steven Chase, “and has given talks at events honouring a Toronto group that advocates for the annexation of Taiwan by China.” Yuen apparently has a “strong relationship with China’s diplomatic mission in Toronto,” and has spoken to the Toronto chapter of the Chinese Freemasons, who have “advocated for what it calls the ‘peaceful reunification of China and Taiwan.’”

How this didn’t raise any red flags (of concern) is anyone’s guess.

Carney isn’t the only member of this Liberal government with, shall we say, a “China problem.” Trudeau had one, too. There was his ludicrous remark as a Liberal MP at a women’s event in 2013, “There’s a level of admiration I actually have for China. Their basic dictatorship is actually allowing them to turn their economy around on a dime.” Trudeau’s China problem got worse when he became PM, including the Two Michaels, Meng Wanzhou affair and still-unresolved allegations of Chinese election interference in the 2019 and 2021 federal elections.

Carney should have studied Trudeau’s repeated failures with China and learned some lessons. He didn’t. The current PM’s stick-handling with this matter has been just as awful as his stance with a hockey stick during a practice session with the Edmonton Oilers.

Long before he entered politics, Carney had established a presence in China.

As Vice-Chair of Brookfield, he engaged in a “fireside chat” with Dominic Barton, then-Canadian Ambassador to China, about the importance of values mentioned in his 2021 book, Values, at the Canada China Business Council’s 43rd AGM and Business Forum in October 2021. National Post columnist Terry Glavin noted on April 4 that Carney “paid several visits to China” while at Brookfield “where he routinely praised Xi Jinping’s leadership and urged the advancement of the Chinese renminbi as a global reserve currency to challenge the U.S. dollar.” Other activities included overseeing a $1 billion investment fund to support the Belt and Road Initiative while he was still Governor of the Bank of England. China’s strategy enabled its banks to gain important access and investment opportunities in over 150 countries and organizations, including the UK’s currency market.

This also stands out when you consider that Carney reportedly secured a $256 million loan last November from the Bank of China for his now-former company, Brookfield Asset Management. This occurred about two months before he jumped into the Liberal leadership race.

Equally interesting? Carney had been an adviser to the Trudeau Liberals since 2020, including as a special adviser and chair of a Liberal Party task force on economic growth last September. Those political appointments overlapped with some of the worst moments of the Chinese election interference controversy in our country. Yet, Carney didn’t think twice (or blink once) about approaching the Bank of China as opposed to non-Chinese banks to secure that loan.

There’s also the revelation from a security task force that an online operation with ties to China’s Communist government was focusing its efforts on Carney. The task force, which includes representatives of Global Affairs, CSIS and the RCMP, had discovered that Youli-Youmian, described by the CBC as “the most popular news account on the social media platform WeChat” and linked “to the Chinese Communist Party’s central political and legal affairs commission,” was attempting to “amplify” Carney’s position on the United States along with his credentials.

It’s highly unlikely that Carney knew about this operation. It should worry him that the Chinese Communists were focusing on his leadership and ideas. Alas, his long-standing relationship with China makes one wonder if he’s at all concerned.

Michael Taube, a longtime newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers