All 144 Conservative MPs have signed an open letter condemning antisemitism in Canada, an apparent response to a similar letter signed by less than a fifth of the Liberal caucus.

The letter came late this week after a targeted attack at a kosher grocery store in Ottawa on Aug. 27, when

in what police have called a “hate-motivated crime.” A 71-year-old man was arrested and charged with aggravated assault and possessing a dangerous weapon.

Days later, on Aug. 31, Liberal Quebec MP

Anthony Housefather said in a post on X

that he signed an open letter along with 31 other Liberal MPs, issuing a call to action. However, there was a lack of signatures from the other 137 Liberals who make up Prime Minister Mark Carney’s caucus. (There are a total of

listed by the House of Commons).

On Thursday, Conservative Ontario MP Melissa Lantsman said on social media that her Conservative colleagues would “stand up and protect the Jewish community in Canada, even when the government won’t.”

She shared an open letter signed by every Conservative MP, including leader Pierre Poilievre.

All Conservatives will stand up and protect the Jewish community in Canada, even when the government won’t. pic.twitter.com/gZHT7bFJpJ

— Melissa Lantsman (@MelissaLantsman) September 4, 2025

“Conservatives are outraged by yet another vile antisemitic attack, this time at a grocery store in Ottawa. Since Hamas’ brutal attack on October 7, 2023, anti-Jewish hatred has skyrocketed on our streets and in our neighbourhoods. For too long, the government has been silent and absent,” the letter says.

Data from Statistics Canada revealed an uptick in police-reported

hate crimes against the Jewish community in Canada

in 2023. The majority — 70 per cent — of such crimes were directed at Jews that year, according to the StatCan data. On Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas terrorists murdered 1,200 people and sparked an ongoing war with Israel.

Jewish advocacy group B’nai Brith Canada released a

in April. There were a total of 6,219 incidents targeting Jews in the country in 2024, it said — the highest number documented by the group since its first report in 1982.

B’nai Brith Canada applauded the efforts made by the Conservative caucus and its “moral clarity.”

“A unanimous response to hate should not be controversial. The devolving crisis of antisemitism requires every MP to act now,” the group said in a post on X on Thursday. “As parliament resumes, it is imperative that tangible actions be implemented to address this crisis. How our government tackles antisemitism will demonstrate its commitment to human rights and Canadian values.”

The moral clarity demonstrated by the Conservative caucus should be emulated by every party in Canada. A unanimous response to hate should not be controversial. The devolving crisis of antisemitism requires every MP to act now. As parliament resumes, it is imperative that… https://t.co/AGW5WHk61Q

— B’nai Brith Canada (@bnaibrithcanada) September 4, 2025

The Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, another Jewish advocacy group in Canada, urged elected officials to take concrete action against the “rise of antisemitism.”

In a post on X on Thursday, it said that antisemites should be held accountable with “real criminal consequences,” parties should “boost funding and partnership with community security” and work to “close loopholes in Canada’s anti-terror laws.”

It also said that safe access zone legislation should be implemented urgently. A safe access zone is an area protected so that people can get to it freely and safely. It can include institutions like schools, clinics or places of worship.

The

that in Toronto, a bylaw came into effect on July 2 permitting more than 18 Toronto Jewish institutions and one mosque to be listed as “safe access” zones. Protests are not allowed within 50 metres of the buildings’ entrances.

The CPC caucus has taken a unanimous stance in condemning the rise of antisemitism and voicing support for our community.

As Parliament resumes, we urge elected officials at all levels of government and across all parties to take concrete action:

– Hold antisemites accountable… pic.twitter.com/3WmHie4ODM

— CIJA (@CIJAinfo) September 4, 2025

CIJA also asked politicians to “protect Jewish participation in civic life.”

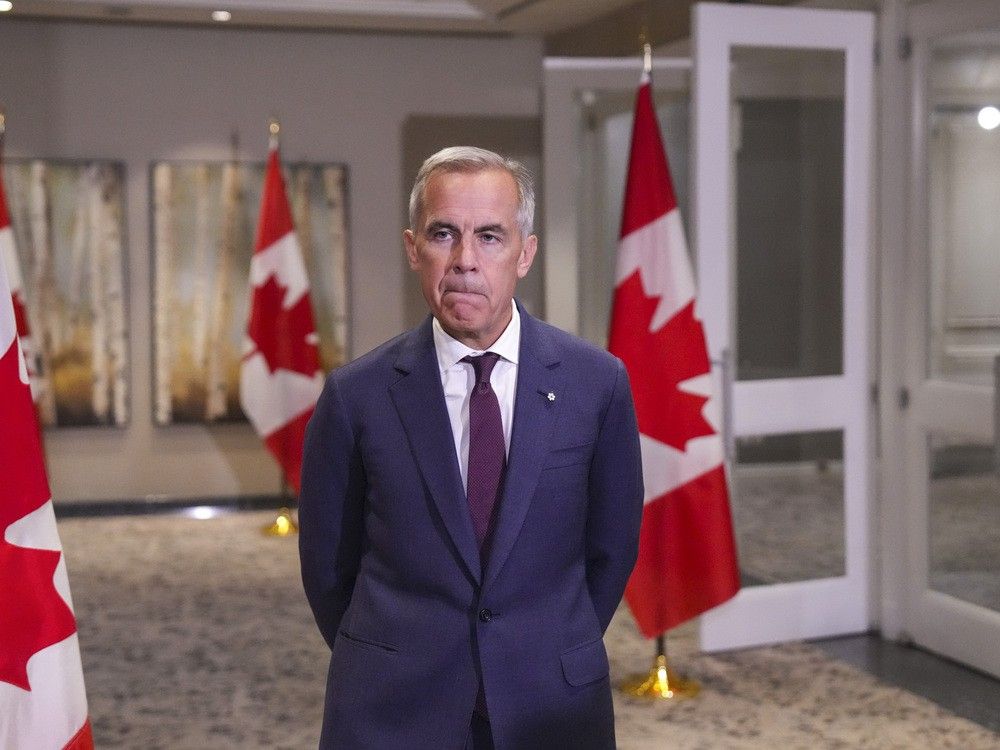

Carney

, calling it “senseless” and “disturbing.” He told Canada’s Jewish community that they were “not alone” in a post on X on Aug. 29.

“We stand with you against hate and threats to your safety, and we will act to confront antisemitism wherever it appears,” he said.

His signature did not appear on the open letter shared by Housefather.

Conservative Ontario MP Don Stewart commented on Housefather’s post, saying a total of 32 signatures from the Liberals was “not very many.”

32 Liberal MPs support the right to safety of Jewish Canadians. That is not very many. There is only one party in Parliament whose entire caucus supports the safety of Jewish Canadians. One. The @CPC_HQ Conservative Party of Canada. See you soon.

— Don Stewart (@donstewartTO) August 31, 2025

“There is only one party in Parliament whose entire caucus supports the safety of Jewish Canadians,” wrote Stewart, referring to the Conservative Party of Canada.

When a business account on X asked Housefather if the other 137 Liberals did not want to sign the open letter, the MP

, “Of course not.”

“The letter was drafted and signatures gathered over 24 hours on a holiday weekend. Originally it was going to be from Jewish caucus and then we asked some others,” he said, adding that “virtually everyone who was asked signed on” and others did when they saw the open letter when it was released.

Housefather’s office did not immediately respond to a request from National Post asking if other Liberal MPs have since signed the letter.

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our daily newsletter, Posted, here.