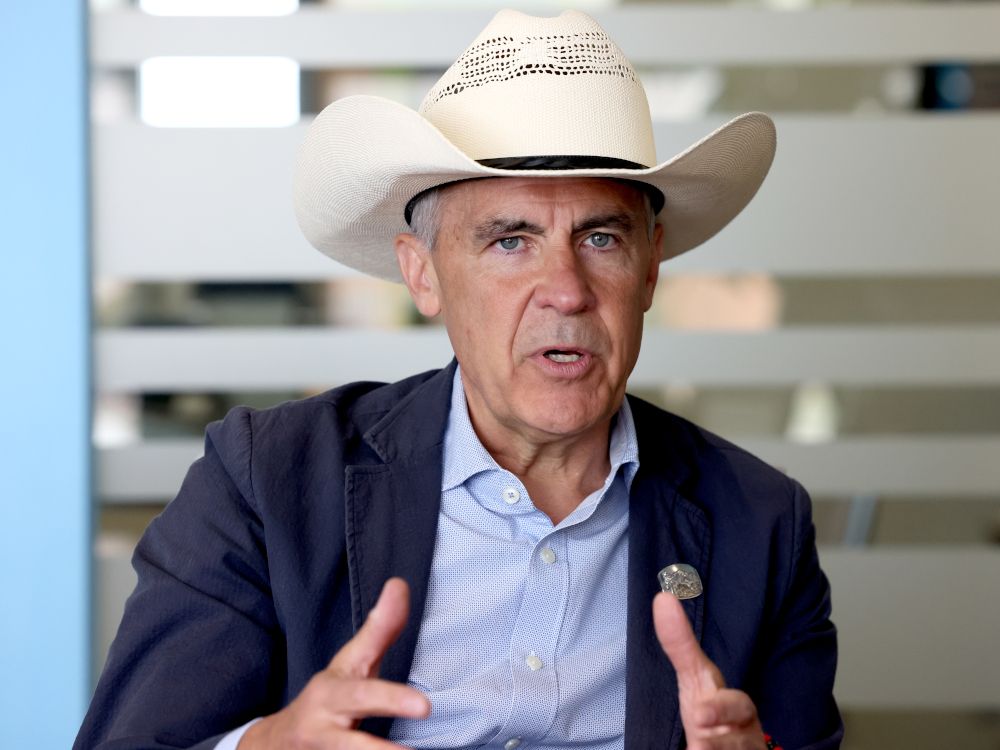

CALGARY — “I want to salute the horse,” said Sgt. Major Scott Williamson, riding master of the

at the Calgary Stampede this year. “No horse, no Stampede. No horse, no RCMP. No horse, no Western Canada as it is,” he said.

I was back home in Calgary for the Stampede this year, the first time in twenty-five years. Even as a teenager, I was less than eager for the midway rides, carnival games and stomach-churning concessions. In any case, those are the same at any civic fair, wherever it may be.

What makes the Stampede, more than the cowboy hats and pancake breakfasts, is the livestock, the animals, and – in particular — the horse. The agriculture barns, cattle judging, livestock auctioneering, rodeo and chuckwagon races put the animals that built the West front and centre. The official title (used to be, at least) the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede, and the former part survives in the agricultural component of the ten-day civic festival.

This year the RCMP — M for “mounted” — Musical Ride was on hand, opening their Alberta tour in Calgary. The gleaming black horses and red-serge constables are one of Canada’s most distinctive symbols, so much so that they were chosen to lead the funeral procession of Her Late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

It’s more than impressive equine choreography, though. That’s the point the master of the ride was making in his tribute to the horse. The partnership between man and horse is not an equal one, but without the horse, man’s capacity to live and explore the vast Canadian West would have been severely limited, if not impossible. Even ancient customs like the Indigenous buffalo hunt were made easier by the use of horses.

The Spanish conquistadors knew that well, keeping meticulous records of each stallion and mare they brought over from Europe. The American cowboy knew that well, considering horse-thieving a capital crime. The early Parliament of Canada knew that well, passing legislation to create a “mounted” police force in the newly acquired Rupert’s Land — the North-West Mounted Police.

No horse, no Western Canada — at least as we know it today.

Williamson’s brief apologia for the horse was necessary. The actual “Cowboys and Indians” of Alberta today were a bit on the defensive at the Stampede. Twenty-five years or more of environmental attacks on the western way of life — agriculture and oil, rodeo and ranching — have left their mark.

Environmentalists protest

; ranchers in the agricultural barns argue that cattle keep the grasslands vibrant and the grass keeps the deadly carbon at bay.

You couldn’t pass a stall or booth without being told how well farmers look after their chickens, pigs, and sheep.

Animal rights activists protest the chuckwagon races, so every half hour, the announcer reminded us that racehorses love to race, are bred for racing, and if not for chuckwagon racing, would be retired to a grim end after only two or three years on the thoroughbred track.

At the rodeo, it is repeatedly emphasized that the bulls and bucking horses live a rather pampered life — attentive breeders, owners, veterinarians, and cowboys tend to their every need for what amounts to a few minutes of work a week.

Celebrating all that was easier at the Stampede a generation or two ago. The defensive posture is the product of a more hostile political climate. On the Stampede grounds themselves, though, the tens of thousands cheering the chuckwagons and calf ropers are genuinely enthusiastic.

On another front, the Stampede is more comfortable and less defensive than Canadian society as a whole, namely in its relationship with Indigenous peoples. The history of Alberta has lights and shadows like other places, but the province’s development has included a partnership of Indigenous tribes and arrivals from overseas or Eastern Canada.

Indigenous peoples have been part of the Stampede since the beginning, and the biggest daily events include powwow dancers. The past is honoured — even if the pyrotechnic-framed aerobatic motorcycles are more exciting for the audience, including Indigenous teenagers.

That comes rather naturally in Calgary. Long before anyone heard of land acknowledgments, the major roads in Calgary had Indigenous names: Crowchild Trail, Blackfoot Trail, Sarcee Trail, Piegan Trail, Deerfoot Trail. The magnificent new ring road — perhaps the most scenic urban highway in North America — is called Stoney Trail.

There are land acknowledgments aplenty at the Stampede, but the difference is that a good number of Calgarians actually recognize the names of the various tribes and even know where in Alberta they live today. No end of Ontario leaders stumble and mumble their way through land acknowledgments, having no idea of whom and of where they are speaking. Every Calgarian can pronounce Tsuut’ina and knows where they live.

In that, Alberta’s past is also the path for the future. Partnership in resource development is what Alberta’s Indigenous leaders want. Horses then, hydrocarbons now.

It’s possible to imagine a Calgary festival without the agricultural element and the animals, but it wouldn’t be the Stampede, which reminds us that our food, our prosperity, our history and our culture come from the land and the animals who work — and play and race — upon it.

National Post