The century-old history of Japanese anime is both fascinating and complex. Many of the early shorts are lost, although a few examples remain like Ōten Shimokawa’s Imokawa Mukuzo Genkanban no Maki (The Story of the Concierge Mukuzo Imokawa) and Jun’ichi Kōuchi’s Namakura Gatana (The Dull Sword), both produced in 1917. Western-based cartoons in Europe and the U.S., which were once important influences on anime, have largely been replaced with domestic tales involving mecha, super robots and real robots. The subject matter has always been diverse, from Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli’s fantastical masterpieces to Katsuhiro Otomo’s awe-inspiring Akira (1988).

One common theme has been the connection between anime and nature. So much so, that a permanent bridge has been created between anime and Buddhism in a rather unique fashion.

We’ll get to this shortly.

A few days ago, I came across a widely-viewed post on X, the old Twitter, containing an anime. I didn’t immediately recognize the animator or animation style, and saved it for later. When I went back to the original post, I quickly realized what I had come across. This was the handle of Soka Gakkai, a Japanese Buddhist religious movement that’s had a long and somewhat controversial history. The anime was Journey to Hiroshima, based on one of the popular children’s stories written by Daisaku Ikeda.

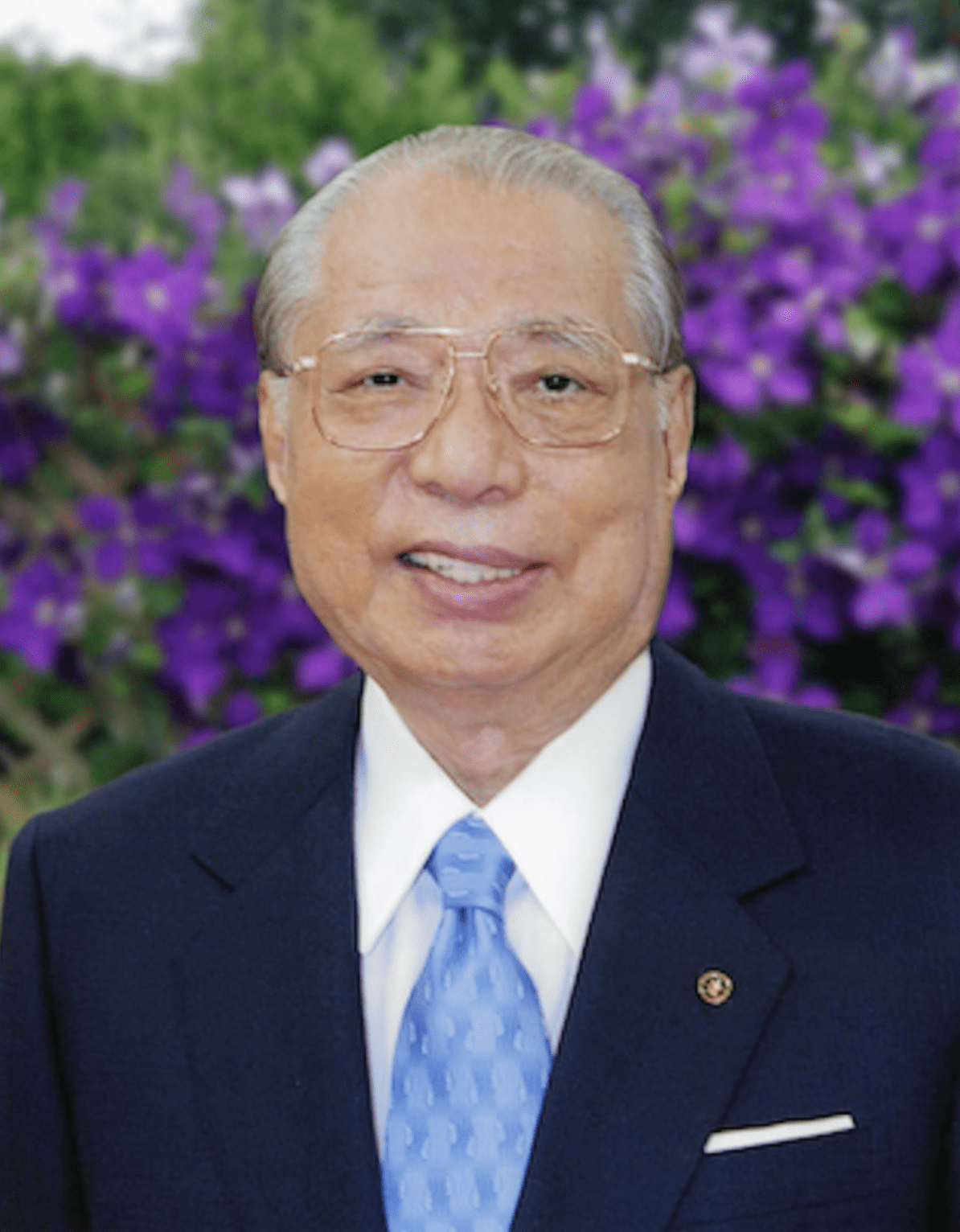

This is a name that some readers may recognize. Ikeda served as Soka Gakkai’s third president from 1960-1979, and has been its honorary president since 1975. He’s the founding president of Soka Gakkai International, which reportedly has more than 12 million adherents across 192 countries and territories. He founded the Soka School System, which oversees everything from kindergarten classes to universities. He founded Kōmeitō, a political party that started on the centre-left, shifted to the centre-right and was part of two right-leaning Liberal Democratic Party coalitions in Japan. He was involved in reopening Japan-China relations in the 1960s.

Ikeda has spoken at conferences related to peace, women’s rights, and Buddhism and science. He’s been involved in interfaith dialogue, including his work with Rabbi Abraham Cooper and the Simon Wiesenthal Center to help curb anti-Semitism in Japan. He’s met and spoken with world leaders such as South Africa’s Nelson Mandela, China’s Zhou Enlai and the old Soviet Union’s Mikhail Gorbachev, as well as political dignitaries like then-U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and then-UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim. He even formed a long-standing friendship with British historian Arnold J. Toynbee.

Ikeda has also been a prolific writer. His books tackle everything from history to poetry. His multi-volume historical novel, The Human Revolution, has been translated into various languages, sold millions of copies and turned into two films. His various children’s stories like The Cherry Tree, The Princess and the Moon and The Snow Country Prince have won significant acclaim from domestic and international readers alike.

A weekly anime series of 14 episodes based on Ikeda’s children’s tales was broadcast on the National Geographic Channel in 2007. It appeared in countries like India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan. The Sri Lanka Rupawahini Corporation, a national broadcaster, then aired 17 episodes in Sinhalese in 2008, beginning with Kanta and the Deer.

A grand total of 18 episodes, plus a short introduction to Ikeda, have been made. They’re all available in several languages in an official YouTube channel, Daisaku Ikeda Children’s Stories. (Soka Gakkai promoted it in a March 28, 2020 tweet/post during the COVID-19 pandemic. Wish I had seen it at that time.)

Where’s the best place to start? I’d suggest the three episodes of The Snow Country Prince, in which a young villager named Goichi takes care of an orphaned baby swan. Alexander’s Decision is the intriguing story of Macedonia’s King Alexander, who is at war with Prussia – where his childhood friend Philip lives. The Prince and the White Horse and The Cherry Tree are both enjoyable, too.

You honestly can’t go wrong with any of them.

Each anime is positive, powerful and uplifting. The adventures take place in real historical periods as well as magical realms. The stories are told from a child’s perspective, where young hearts and minds face their challenges in a more optimistic and hopeful manner. Important principles such as friendship, peace and courage guide their every move.

Many lessons of Buddhism can therefore be found within the anime of these children’s stories. Ikeda and his animation team obviously aren’t the first to incorporate Buddhism, Shintoism or aspects of nature into this popular medium. Nevertheless, they helped build a permanent bridge between anime and Buddhism that appeals to both devout followers and non-believers.

That’s a fine accomplishment on Ikeda’s long, winding road to nirvana.

Michael Taube, a long-time newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.