William Henry Jackson was one of the first photographers to document the American West. His work in this field either led or influenced the development of Yellowstone Park, the National Parks Service, modern thinking related to conservationism and more.

The Andrew Smith Gallery described Jackson as “America’s pioneer photographer.” He published “tens of thousands of prints of his work and that of other photographers, wrote extensively, painted and sketched, and built two of the most successful photographic view companies in the history of photography, his studio in Denver and later the Detroit Photographic Publishing Company.” Moreover, the gallery pointed out that he was “best known for his dramatic and descriptive nineteenth-century Western-landscape photographs” and worked in “formats ranging from cdvs to gigantic single print multi-mammoth plate panoramics up to 92 inches wide.”

Alas, this impressive life and career has slowly faded from public memory. The release of a new graphic biography, Photographic Memory: William Henry Jackson and the American West, published by Abrams ComicArts, has given new life to this important historical figure. Who is the book’s author? Jackson’s great-grandson, Bill Griffith.

Some readers may be familiar with Griffith’s work as a cartoonist and in the world of underground comix. One of his earliest creations was Mr. The Toad, depicted as an “angry amphibian” in Lambiek.net, along with his contributions to the one-shot comic book ProJunior and the anthology Laugh in the Dark. His most famous creation is Zippy the Pinhead, which was partially inspired by the microcephalic Schlitzie from the 1932 film Freaks. Zippy’s first appearance was in Real Pulp Comics #1 in March 1971. The iconic character has been syndicated by King Features since 1990, and has appeared in various publications such as Arcade, National Lampoon and the San Francisco Examiner.

Here’s another way that you may be familiar with Zippy. If you’ve ever heard or uttered the phrase, “are we having fun yet?,” that’s who said it first. It’s been part of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations for quite some time now.

Griffith has produced some fascinating work in recent years. This includes Invisible Ink: My Mother’s Secret Love Affair with a Famous Cartoonist (2015), Nobody’s Fool: The Life and Times of Schlitzie the Pinhead (2019) and Three Rocks: The Story of Ernie Bushmiller: The Man Who Created Nancy (2023), which I reviewed for the Wall Street Journal. His newest book may be the most impressive to date.

Photographic Memory can be best described as a series of flashbacks on a life well lived. Jackson, who reached the ripe old age of 99 (and missed seeing the birth of his great-grandson by only two years), thinks back to his days as a photographer and discovering the beauty and grandeur of the American West. He’s flooded with memories of his family and photographic experiences. His early days as an apprentice, retoucher and budding camera genius are covered. The art of photography was very different in Griffith’s day. There were long wait times for an image to be developed. The subject had to sit or stand completely still for several minutes or risk the possibility of a blurry photo. A small mistake could turn into a big production, which Jackson and other photographers worked hard to prevent.

Jackson served in the Civil War as a sketch artist for the Union Army. “Once the war was in the rearview mirror,” Griffith wrote, “Jackson returned to Rutland his old job hand-tinting photographs at Frank Mowrey’s studio.” He earned twelve dollars a week, which gave him some spending money to head out with friends and his “sweetheart,” Caddie Eastman. He was also amusingly part of a small group of “Rutland young bloods” known as S.S.C., which apparently stood for “Social Sardine Club,” who met regularly and ‘enjoyed their hush-hush notoriety.”

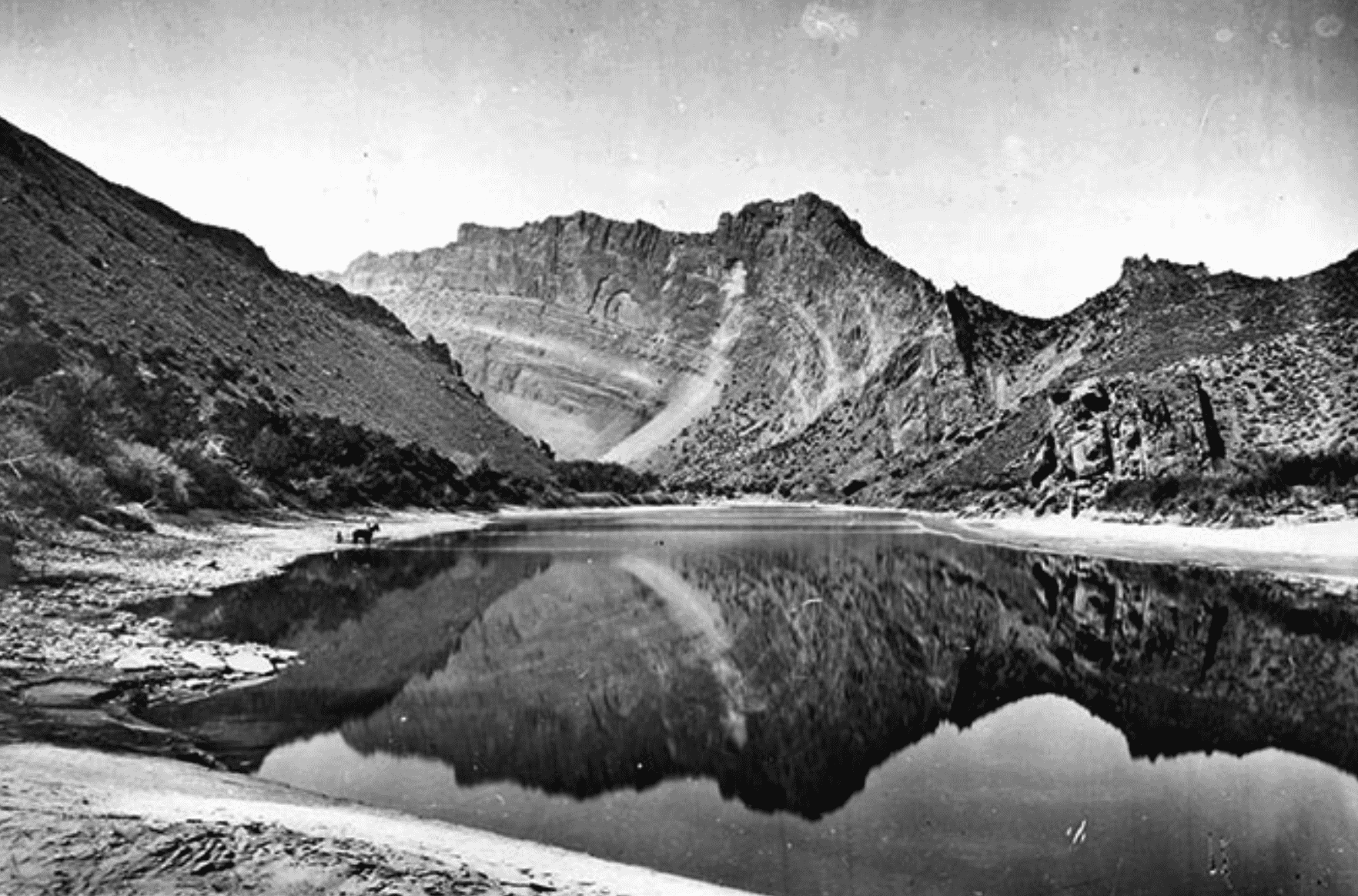

The most interesting passages relate to Jackson’s experiences in the American West. Griffith, a superb cartoonist and writer, brings his great-grandfather’s photographic journey to life in illustration after illustration. The chapter on Yellowstone, which focuses on the photos that were “instrumental in the establishment of the nation’s first national park,” is an artistic triumph. From the Old Faithful Geyser to the Mammoth Hot Springs, one begins to understand how the “rich subject matter” was carefully captured in early cameras and rudimentary technology. Few were as talented as Jackson, and even fewer could have succeeded on the level that he did.

Other fascinating experiences include relations with Native communities, photos in Colorado and the Rio Grande, and excursions to Mexico, Paris, the ruins of Carthage and Egypt. “Harper’s Weekly was using Jackson’s photos to advance their own agenda,” Griffith wrote, which was part of his 1894-1896 trip as a member of the World’s Transportation Commission organized by Joseph Gladding Pangborn. Readers will discover that Jackson was also the “father of the American picture postcard.” Regular correspondence to Emilie, his beloved second wife, affords us some insight into the photographer’s thoughts, hopes and dreams. And, in true Griffithian fashion (so to speak), the epilogue featuring Yogi Bear and Jellystone Park has to be seen to be believed!

Photographic Memory is an exceptional graphic biography. Griffith has created an artistic love letter to Jackson, the great-grandfather he never knew, and honoured his life and career to the point of pure perfection. It’s a family photo that will always be treasured.

Michael Taube, a long-time newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.