ATLANTA (AP) — Two ballot drop boxes in the Pacific Northwest were damaged in a suspected arson attack just over a week before Election Day, destroying hundreds of ballots at one location in Vancouver, Washington.

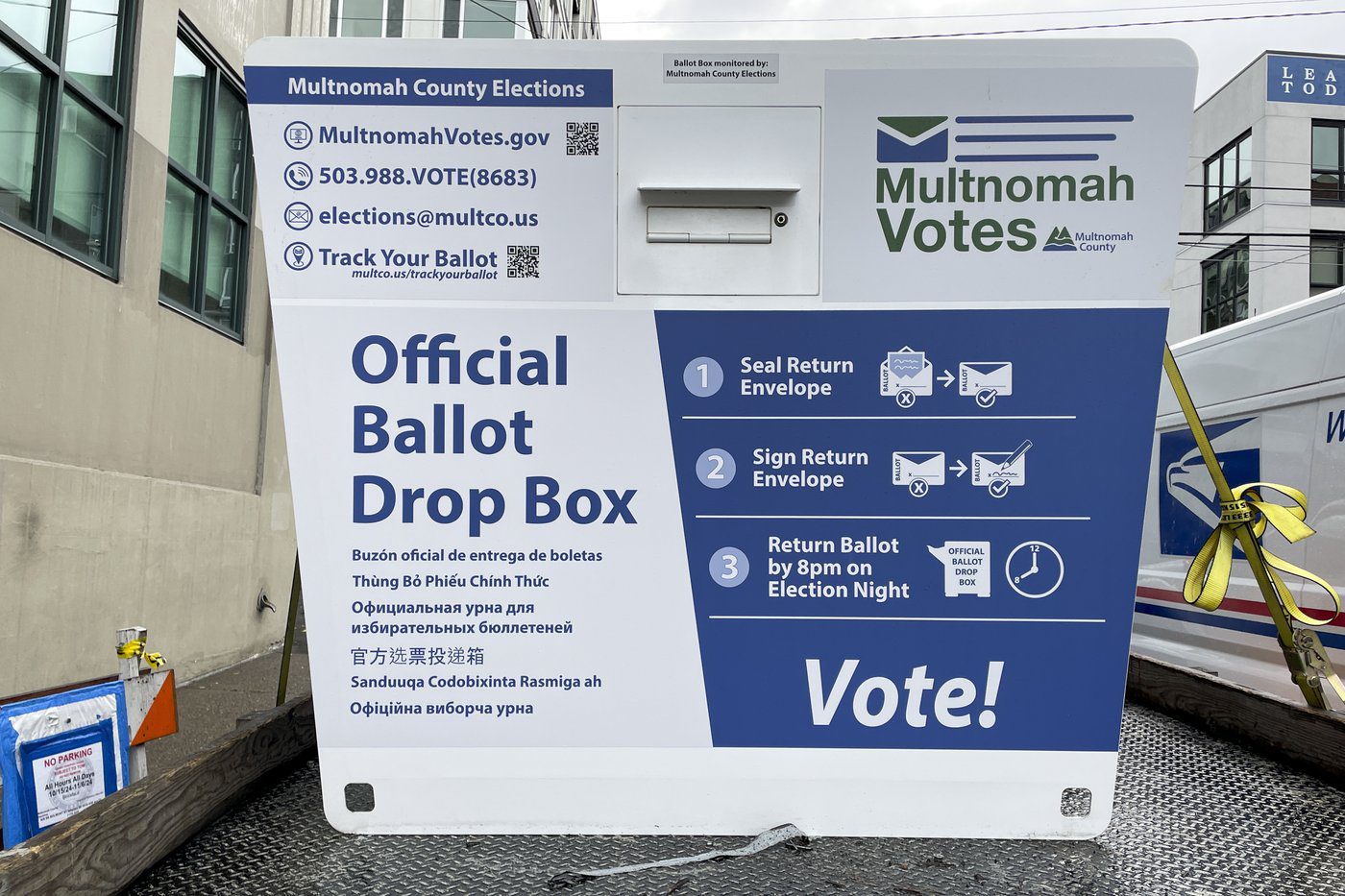

At the other, in neighboring Portland, Oregon, it appears a fire suppression system worked to contain the blaze and limited the number of ballots damaged to three. Authorities are reviewing surveillance footage as they try to identify who is responsible.

Here’s what happened, how rules and security measures about drop boxes vary across the country, and how election conspiracy theories have undermined confidence in their use.

What do we know?

Police said incendiary devices started the fires in the drop boxes in Portland and Vancouver. Authorities said evidence showed the fires were connected and that they also are related to an Oct. 8 incident when an incendiary device was placed at a different drop box in Vancouver.

Multnomah County Elections Director Tim Scott said his office was planning to contact the three voters whose ballots were damaged in Portland to help them get replacements.

In Vancouver, hundreds of ballots were lost at a ballot box at the Fisher’s Landing Transit Center when the drop box’s fire suppression system did not work as intended. Clark County Auditor Greg Kimsey said the box was last emptied at 11 a.m. Saturday. Voters who dropped their ballots there afterward are being urged to contact the office to get a new one.

The office will be increasing how frequently it collects ballots and changing collection times to the evening to keep ballot boxes from remaining full overnight when vandalism is more likely to occur.

Kimsey described the suspected arson as “a direct attack on democracy.”

When and where can drop boxes be used?

Drop boxes have been used for years in states such as Colorado, Oregon, Utah and Washington, where ballots are mailed to all registered voters.

They grew in popularity in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, as election officials sought options for voters who wanted to avoid crowded polling places or were worried about mail delays.

In all, 27 states and the District of Columbia allow ballot drop boxes, according to data collected by the National Conference of State Legislatures. Six others don’t have a specific law but allow local communities to use them.

Placement can vary widely. In some communities, they’re located inside public buildings, available only during office hours. Elsewhere, they are outside and accessible at any hour, typically with video surveillance or someone watching.

Sporadic problems have occurred over the years.

In 2020, a few drop boxes were hit by vehicles, and one in Massachusetts was damaged by arson. In that case, most of the ballots were legible enough for voters to be identified and sent replacements. A drop box also was set on fire in Los Angeles County in 2020.

How should they be secured?

The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency advises state and local election officials to place drop boxes in convenient, high-traffic areas that are familiar to voters, such as libraries and community centers.

If drop boxes are not staffed, they should be secured and locked at all times, located in well-lit areas and monitored by video surveillance cameras, the guidance says. Many are bolted to the ground, surveilled with cameras or confined to public buildings during business hours, where they can be monitored.

How have conspiracy theories contributed to concerns around drop boxes?

Ballot drop boxes have been in the spotlight for the last four years, targeted by right-wing conspiracy theories that falsely claimed they were responsible for massive voter fraud in 2020.

A debunked film called “2,000 Mules” amplified the claims, exposing millions to a groundless theory that a ballot harvesting operation was depositing fraudulent ballots in drop boxes in the dark of night.

An Associated Press survey of state election officials across the U.S. found there were no widespread problems associated with drop boxes in 2020.

Paranoia about drop boxes continued into the 2022 midterms, when armed vigilantes began showing up to monitor them in Arizona and were restricted by a federal judge. This year, the conservative group True the Vote launched a website hosting citizen livestreams of drop boxes in various states.

In Montana, where an important U.S. Senate race is on the ballot, Republicans recently seized on an unsubstantiated ballot box tampering claim to raise money off doubts about the electoral process.

How have states responded since the 2020 election?

Republican lawmakers in several states sought to tighten rules around mail voting after the 2020 election, and much of their focus was on the use of ballot drop boxes.

Six states have since banned them: Arkansas, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina and South Dakota, according to research by the Voting Rights Lab, which advocates for expanded voting access.

Other states have restricted their use. This includes Ohio and Iowa, which now permits only one drop box per county, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

In Georgia’s Fulton County, which includes Atlanta and has over 1 million residents, 10 ballot drop boxes are available for this year’s presidential election. That’s down from 38 four years ago under an emergency rule prompted by the pandemic. It’s the result of an election overhaul by Georgia Republicans in response to former President Donald Trump’s false claims of a stolen election.

Overall, 12 states prohibit drop boxes or do not list drop boxes as an approved method of returning a ballot, according to data collected by the National Conference of State Legislatures. Five other states do not have a state law and do not use drop boxes.

Drop boxes had been used for years in Wisconsin, one of this year’s presidential battlegrounds, but support for them has split along ideological lines since 2020. In Wausau, the conservative mayor carted away the city’s lone drop box, an action that’s under investigation by the state Department of Justice. The drop box has since been returned and is in use.

___

Swenson reported from New York.

___

The Associated Press receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Christina A. Cassidy And Ali Swenson, The Associated Press