CALGARY — Oral Virtue first met Newfoundland-based Canadian soldiers as a child growing up in Jamaica, never forgetting their friendliness, openness and the way they spoke this “funky foreign language.”

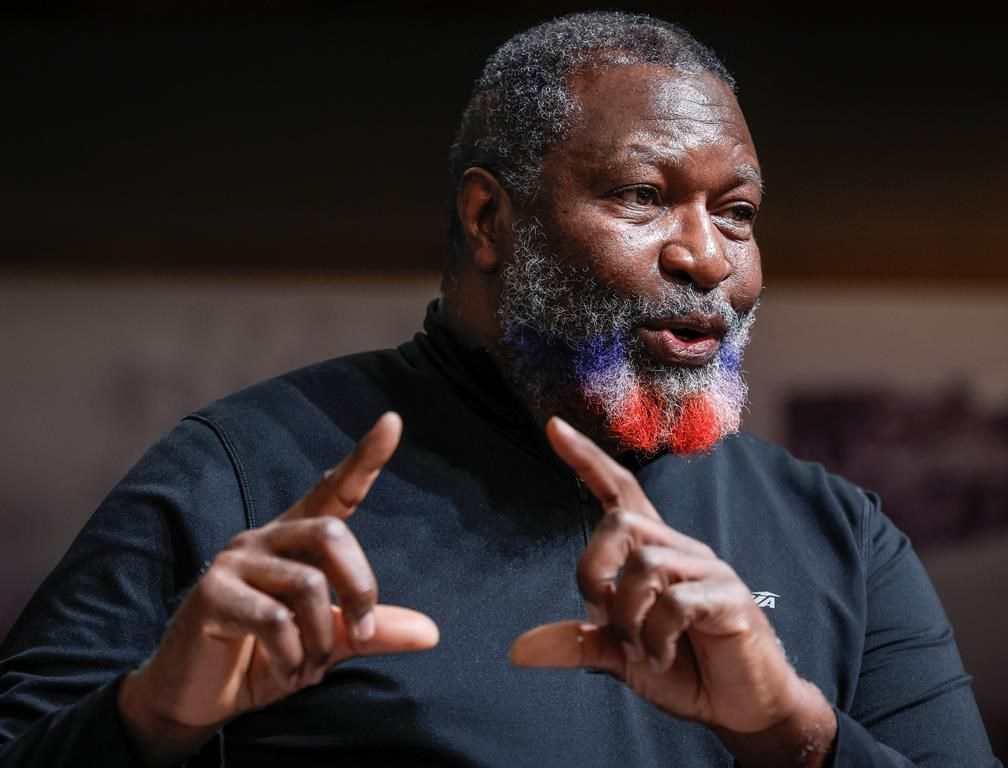

More than five decades later, Virtue, 61, recalls a lifetime of service as a soldier while viewing the Black History Month exhibition at the Military Museums in Calgary.

“It never left my heart. Up to this day, I can still remember seeing those first Canadians (in Jamaica),” Virtue said in an interview.

“They are so polite, so nice. But we can’t understand a single word they’re saying because they’re speaking this funky, foreign language,” he said with a laugh.

Memories of the Maple Leaf meshed with Virtue’s family history and his innate love of all things military.

His father served in the Second World War with Great Britain.

Virtue and his family moved to Ontario, and Virtue eventually joined the Canadian Armed Forces, serving on deployments in Cyprus, Bosnia and elsewhere in Europe before retiring in 2007 from the Lord Strathcona’s Horse armoured regiment.

Virtue said while everyone was supposed to serve as equals, shoulder to shoulder, he signed up with his eyes wide open as a Black man.

“I wasn’t blind to what was happening,” Virtue said.

“I was definitely aware of the racism.

“When I joined, there were a couple of guys that were from the Caribbean, and they talked to me about what I should expect. Their experience paved the way for me.”

Allan Ross, a volunteer researcher who curates the Black History Month exhibit, said the roots of military service for Black Canadians dates back two centuries — helping the British fight off the Americans in the War of 1812 and assisting in stopping the rebellion in Upper Canada in 1837.

Canada’s first Black physician, Anderson Abbott, served in the U.S. Civil War, he added. Abbott was also an attending physician to U.S. president Abraham Lincoln.

Ross said any underlying racism became glaringly obvious during the Boer War in South Africa from 1899 to 1902 — a conflict that saw 7,000 Canadians volunteer for service alongside British forces.

Ethnic soldiers, said Ross, were eager to enlist but were turned away, given the prevailing sentiment that they would not fight or would falter when bullets started flying.

“We first hear the term, ‘It’s a white man’s war’ in the Boer War,” said Ross.

As Canada’s participation in conflict continued, discrimination marched in lockstep.

Many Black Canadians were turned away from serving in the First World War, although they were eventually allowed in — not to fight but to work in service roles.

An all-Black battalion, the No. 2 Construction Battalion, was formed in Nova Scotia and was dispatched to France in 1917 to provide lumber for trenches, roads and railways.

In the Second World War, air force and navy officials feared Black soldiers would struggle aboard ships and planes, said Ross.

“They thought the tight confines of an airplane or in a ship might cause conflict or disagreement with some of the other men.”

Ross said acceptance was better in later conflicts in Korea, the Baltics and Afghanistan. The will of Black Canadians to serve has remained strong throughout.

“Why did these men want to fight?” said Ross.

“They wanted to say, ‘We’re Canadians as well. We’re all in this together and we want to prove we are part of this greater group.’”

Virtue said history, in some ways, still repeats itself.

Female soldiers later experienced what Black soldiers went through when it came to combat roles, he said.

“When I was in (CFB) Cornwallis, we had females in our platoons, and they were promised combat roles. Not a single one of them got it,” he said.

“Years later, I went to Europe and I came back, and then we had the very first females inside our vehicles.

“They did end up having a very, very hard time,” he added.

“Discrimination is discrimination.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Feb. 25, 2024.

Bill Graveland, The Canadian Press