Happy Canada Day! As we enjoyed the annual celebration of our great country, complete with food, fireworks and plenty of fun, I decided to do what I like to occasionally do: shifted gears and focused on something different. Let’s deviate away from the (ahem) looniness of Canadian politics and explore the zaniness of animation and comics!

It’s only right that we start off with two older Canadian titles I was re-reading recently.

Karen Mazurkewich’s Cartoon Capers: The History of Canadian Animators is still one of the finest examinations of our local animation industry. There’s some analysis of great National Film Board animated shorts like The Log Driver’s Waltz, The Big Snit and Bob’s Birthday, successful animated TV series/specials like Tales of the Wizard of Oz, Babarand The Raccoons, and Canadian connections to Snow White, Elmer the Elephant and Bugs Bunny. “Insiders joke that Canucks are the gypsy kings of the animated world,” Mazurkewish wrote in the Introduction, but in fact, “Canadians are flexing their graphic muscle in every major international studio.”

Chester Brown’s Louis Riel: A Comic Strip Biography remains one of the more fascinating graphic novels ever produced in this country. It started as a ten-issue serialization published by Drawn & Quarterly between 1999 to 2003, and exploded in popularity when it was published in book form. Brown’s scholarly examination of Riel’s life as a politician and radical Métis leader includes historical references and an extensive series of endnotes from primary and secondary sources. Few graphic novels have ever come close to achieving this high standard.

Let’s move on to other books.

The University Press of Mississippi produces some of the most intelligent opinions and analyses of animation and comic strips. Two books that I recently requested fit this description perfectly. (My thanks to Courtney McCreary.)

Katherine Moeder’s Wide Awake in Slumberland: Fantasy, Mass Culture, and Modernism in the Art of Winsor McCayis a superb exploration into the art and mindset of one of the world’s greatest cartoonists. Her in-depth study of McCay’s magical and highly imaginative comic strip, Little Nemo in Slumberland, is a joy to behold. Moeder suggested that his seminal work “attempted to broaden the audience for comics in several critical ways.” In particular, the strip’s main characters are “situated within a spectrum of childhood types defined in part by class.” Nemo is a “middle-class child of the suburbs,” for instance, and a “perpetual innocent, reminiscent of the gentle dreamers by Jessie Wilcox Smith, with his tousled hair and wide declarations of ‘Oh!,’ – he remains from week to week in a constant state of wonder.” Flip, a clown who is the “mischievous, cynical, cigar-smoking friend” of Nemo’s, has personality traits that distinctly resemble the “trickster street urchins embodied by the Yellow Kid.”

What about Impie, the young African jungle imp who befriends Nemo, Flip and the Princess of Slumberland? He speaks a “gibberish language” and is a stereotypical character whose “exaggerated features recall the theatrical blackface of minstrel performers.” This type of character would be frowned upon in today’s society, but was viewed in a different light in McCay’s time. This racialized example of “boyhood savagery was uplifted as both normal and necessary” and understood to be “an essential step in the journey to productive manhood.” Plus ça change, indeed.

Jean Lee Cole’s How the Other Half Laughs: The Comic Sensibility in American Culture, 1895-1920 is an equally thought-provoking analysis of the evolution of comic strip humour. There was a fundamental switch to a “particularly grotesque form of the comic sensibility” in this time period. George Luks, a talented artist and cartoonist with a Bohemian flair who used “‘schematic,’ suggestive sketching rather than close observation” to help readers “imagine what was happening,” spearheaded the early development of comic grotesque. His colleague Richard F. Outcault, creator of the brilliant Hogan’s Alley and The Yellow Kid, drew ethnic working-class scenes involving young children. His strips were dominated with text that was “written on objects – signs, boxes, fences, the Yellow Kid’s shirt – rather than being spoken by the characters themselves” and enabled the words to “act as labels, applied by Outcault, the mediating consciousness.” Cole also looked at the work of Rudolph Dirks, George Herriman, William Glackens and others to show how they influenced the “New Humour” movement in the newspaper funnies.

Let’s close things out with Fantagraphics, one of America’s finest comics publishers. (My thanks to Eric Reynolds and Tucker Stone.)

Rick Geary and Mathew Klickstein’s Daisy Goes to the Moon: A Daisy Ashford Adventure is an exquisite and unique comic volume. Ashford, an English writer whose most famous work was the 1919 novella The Young Visiters, served as the inspiration for a fantastical journey on a “rokitship.” She met a unique cast of characters, including a “rarther quear fellow” from the Moon named Zogolbythm, Servette the Robot, Mr. B. Blahdel and, in a strange twist, a second Daisy! Her adventure took many twists and turns, to the point where Daisy remarked, “So am I writing this story or is it writing me?”

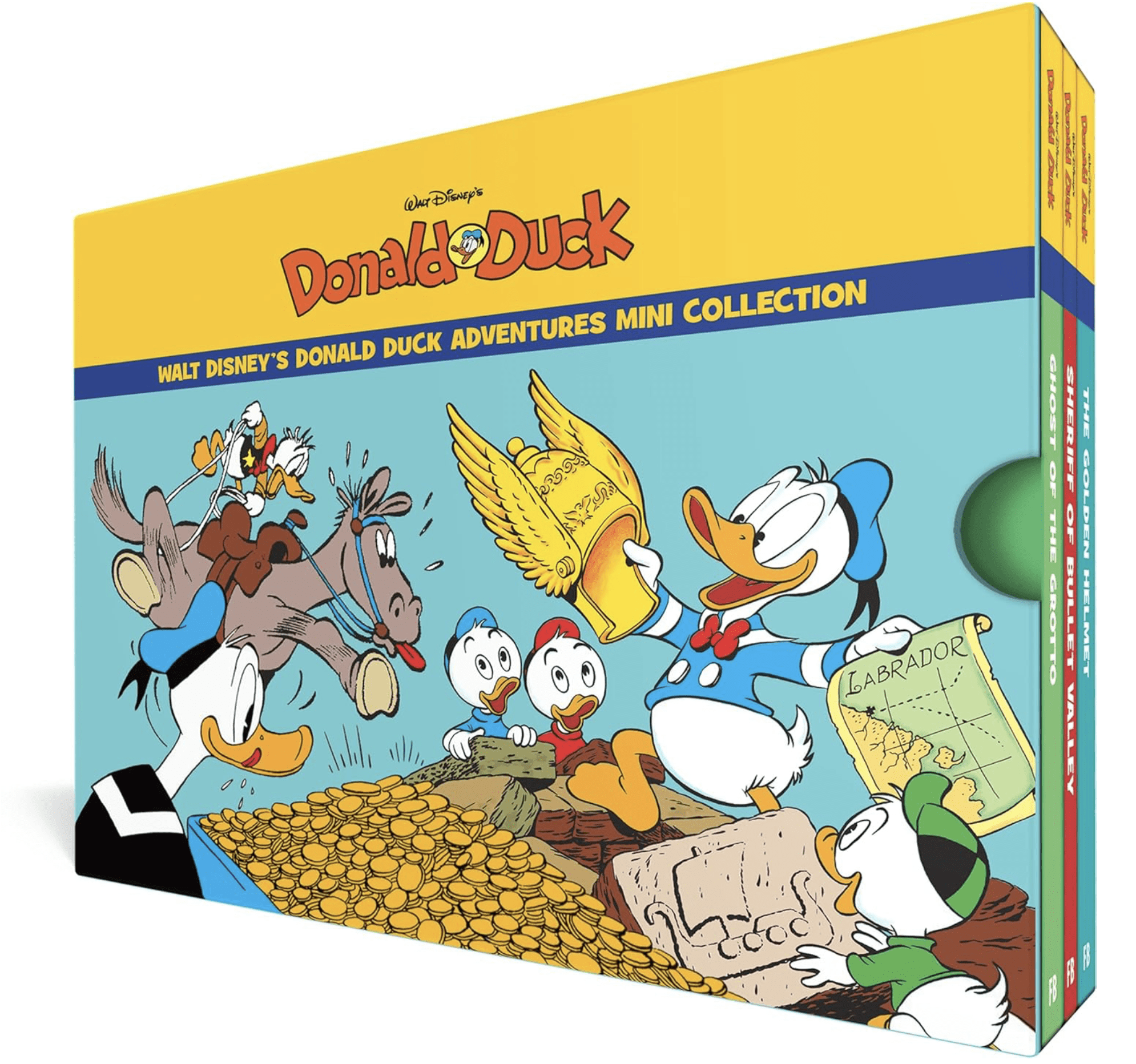

There’s also Walt Disney’s Donald Duck Adventures Mini Collection, featuring the work of legendary cartoonist Carl Barks. Three of his classic comics, Ghost of the Grotto, Sheriff of Bullet Valley and The Golden Helmet, are included in this set. Barks, along with Don Rosa, was the most well-recognized illustrator of Donald Duck. He also created Scrooge McDuck, the wealthy “adventure-capitalist” who still ranks among the most memorable of Disney characters. All three stories hold up well, including my personal favourite, The Golden Helmet, which involves a search by Donald and his three nephews, Huey, Dewey and Louie, to find an ancient Viking helmet located somewhere on the coast of Labrador, Canada.

Comics on Canada Day? Why not, eh?

Michael Taube, a long-time newspaper columnist and political commentator, was a speechwriter for former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper.