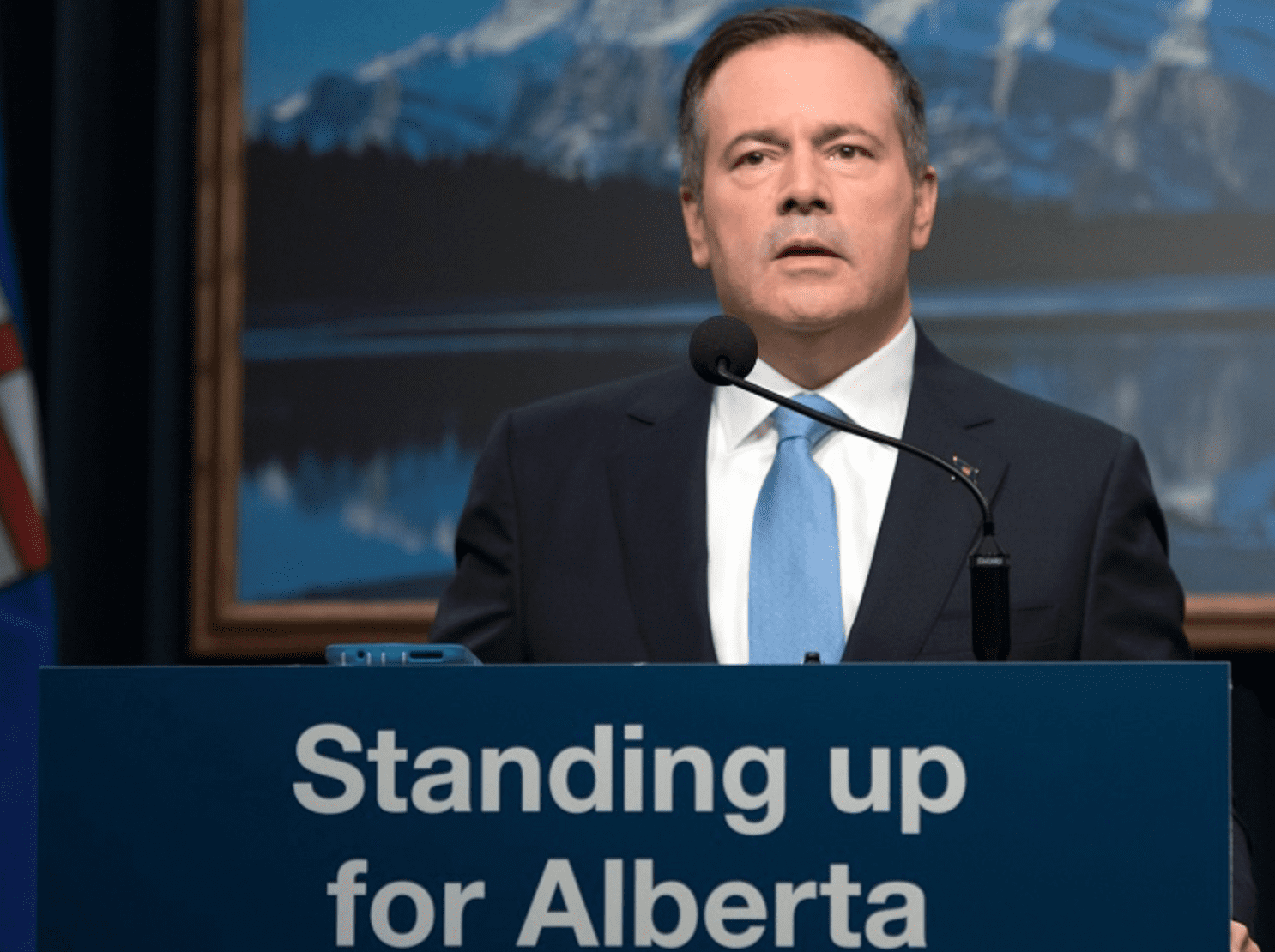

Way back in mid April, as the province confronted the Covid pandemic with such an ample supply of respirators it was able to donate supplies to other provinces, Premier Jason Kenney was effusive in his praise of Alberta Health's procurement professionals.

He held a news conference with a senior official, Jitendra Prasad, praising him and his team for their foresight in preparing for the health emergency.

Implicit in that praise was a recognition that the experience developed by a professional and stable public service saved the day.

Prasad stated it explicitly during the press conference.

"We are very, very fortunate that we have a single health care system in Alberta which has given us an enormous amount of experience in being able to do the things we are doing today."

This week Alberta's health minister announced a plan to cut up to 11,000 public sector health care jobs, outsourcing them to private contractors.

The cuts, at least during the continuing pandemic, won't include nurses or front line clinical staff. Laundry, lab, food services and cleaning staff will be privatized over the next three years. And at least 100 management jobs will be eliminated.

The initial protection of clinical staff is meant to assure the public that front-line health care won't be endangered by these moves. But it's pretty tough to know where a weak or destabilized link in the health care team can spell disaster.

The procurement team, for instance, made a difference at the beginning of the Covid crisis. Who knows if a runaway superbug might make cleaning and laundry even more critical than it is now in some future emergency?

Shandro argues that the provincial plan isn't a matter of lost jobs, but rather just a changing of the employer. But there's no guarantee the same people doing the lab tests and housekeeping now will be the ones hired by private sector contractors. The 100 management jobs will be eliminated, despite Alberta Health Services reputation as having the leanest management in the country. The type of experience the government counted on in April could evaporate in the shift.

The government argues that there is a good deal of privatization in the job classifications about to be hit. The big cities already outsource laundry and in northern Alberta, 70 per cent of lab work is done by a private contractor.

But the fact that not all services have been included until now hints that there may be issues with finding contractors and the complexity of the testing required.

Rural areas, for instance, could struggle to find a private service supplier who will take on small hospitals and clinics without the economies of scale to ensure profit margins.

The whole question of exactly what the cost benefits will be from this exercise is another issue.

The government predicts $600 million will be saved annually once all the cuts are implemented. Shandro admits that's only an estimate. The savings depend on the final contracts with private sector suppliers.

But the intangible cost of the announcement is already being felt, including its toll on labour peace.

Public service unions are already sabre rattling. Guy Smith, president of the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees, is talking about potential strike action.

The unions and the NDP are particularly targeting the bizarre timing of the announcement.

Even though many of the cuts wouldn't be implemented for a year or more, the laying out of the plan in the middle of the Covid second wave is bewildering. Critics all argue the UCP is sowing chaos in a health care system strained to the brink with burned out and overworked healthcare staff.

Back in April Prasad offered his thanks to the government for enabling his team to do such a sterling job preparing the healthcare system for the pandemic.

"A lot of credit goes to the leadership of AHS, to the support we have from the government, the premier personally and the minister."

Ultimately that support apparently pales in comparison to the UCP's ideological imperative to privatize and reduce the public sector.