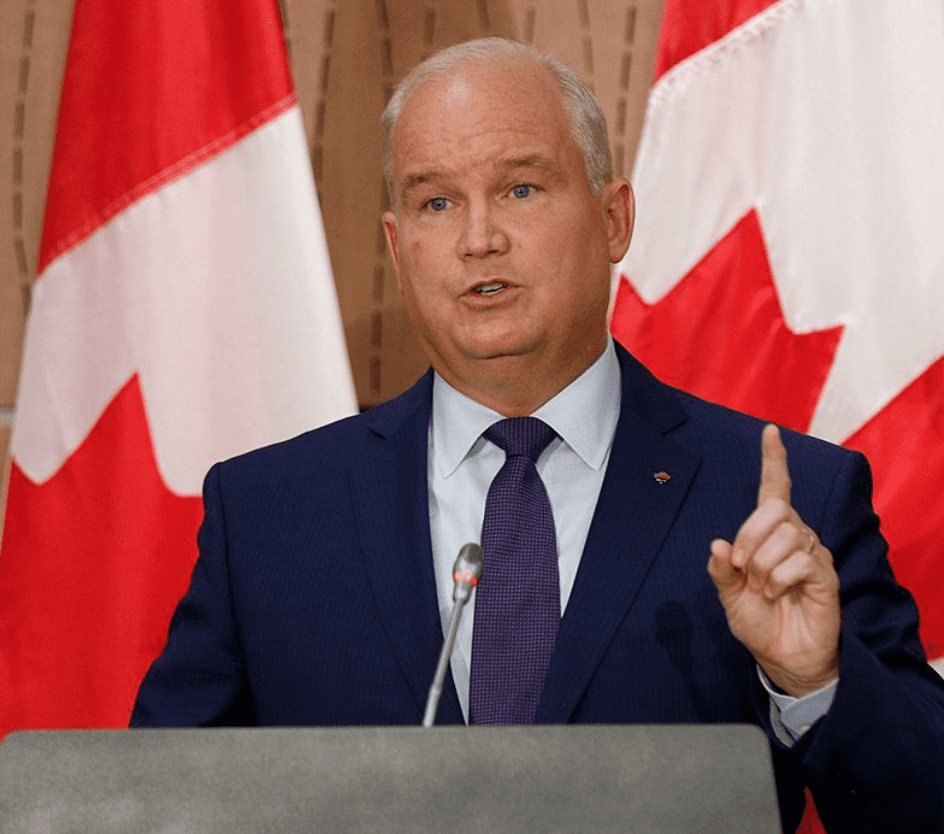

Conservative Party leader Erin O'Toole is coming under a lot of fire for his nationalistic/protectionist "Canada First" rhetoric.

Apparently, such talk doesn't pass muster with economic theory.

One headline I saw, for instance, declared, 'Canada First' might make for good politics, but it's bad economics", while another screamed, "These jobs are not coming back': economists pour cold water on O'Toole's Canada First policy".

Should any of this concern O'Toole and the Conservatives?

Nope.

After all, he's running to be Canada's next prime minister, not the next winner of the Nobel prize in economics.

Indeed, generally-speaking, all politicians routinely promote economic policies that make economists cringe.

Why is that?

Well, the answer is simple; the average voter doesn't care too much about economic theory, they care about perceptions.

When US President Donald Trump gets up on a stage and promises to put "America First" by imposing a tariff on China, economists will point out that, according to their fancy theories, such a policy will only hurt American consumers by driving up the costs of imports.

But many voters will perceive Trump's firm stance as standing up for American workers.

In short, trade protectionism appeals to our tribal nature, which is something O'Toole is undoubtedly banking on when he criticizes "corporate and financial power brokers" who "love trade deals with China that allow them to access cheap labour."

Maybe the economics department at the University of Toronto won't like this view, but it will make sense to a lot of Canadian voters.

Or consider the economic politics of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Keep in mind that even before the COVID crisis necessitated massive amounts of government expenditures, the Trudeau government was spending tax dollars with reckless abandon, which resulted in Canada facing deficits for as far as the eye can see.

That's kind of massive government spending that keeps the economists over at the Fraser Institute up at night.

But did average Canadians care?

Nope.

For most people national debts and deficits are just abstract concerns.

As a matter of fact, back when I was working for an advocacy group called the National Citizens Coalition, I helped compose a study on Canadian attitudes towards fiscal issues.

What we found was a lot of people didn't even understand the concept of a national deficit, nor did they realize the scope or scale of the deficit or debt.

In other words, people weren't even aware of the terms of the debate.

What people perceive, on the other hand, is that government spending ensures they have a good quality health care system, good schools, generous social programs, etc.

And any government that says it will cut spending in the name of fiscal responsibility, will face the wrath of worried voters who want to protect their entitlements.

Of course, the paradox of politics is that those same worried voters don't want to see their taxes increased to pay for all those social programs.

If taxes absolutely must be raised, then they should be paid by "someone else."

This leads politicians on the left to make promises about raising taxes on the "rich" or on "big corporations", a policy which many economists argue would undermine our economic productivity.

By the way, on a side note, when it comes to pushing economic policy, whether it's considered good economics or bad, politicians will usually seek to avoid specifics, since this can lead to trouble.

Recall how in the 2008 federal election the Liberals, under then leader Stephane Dion, promised to implement a "green shift" carbon tax plan, an idea which economists tended to like.

Yet, that didn't stop the Conservatives from immediately pouncing on the scheme, calling it a "tax on everything", an attack which wilted Dion's chances.

That's why it's smart politics to keep any economic policies you want to promote as a politician concise enough to stick on a bumper sticker.

When I was working on a Republican Senatorial campaign, for example, our economic "platform" was short and sweet: lower taxes, smaller government, fairer trade.

That's it. It's all we needed.

At any rate, my point is, O'Toole shouldn't fret if economists don't like his policies.

As American economist Thomas Sowell, once put it, "The first lesson of economics is scarcity … The first lesson of politics is to disregard the first lesson of economics."

Photo Credit: CBC News