In the wake of the swift passage of two pieces of emergency legislation designed to deal with the fallout of the global COVID-19 pandemic with little-to-no scrutiny, and with yet more emergency legislation on its way as Parliament is set to reconvene sometime in the next few days, the Samara Centre for Democracy decided to take a closer look. On the one hand, it's good to get a somewhat more rigorous look at the metrics of what did and did not happen with these two pieces of legislation but on the other hand, these analyses tend to fall back to some of the usual problems that Samara reports have.

One of the most trenchant parts of analysis in the report was the comparison to how other similar parliaments, both in the UK and Australia, had dealt with their own emergency legislation.

By comparison, the UK government's Coronavirus Bill was introduced four days before being discussed in Parliament. It was debated for six hours by MPs and seven hours by the House of Lords over a three-day period. As with Bill C-13, the Coronavirus Bill originally would have allowed the UK government to use its emergency powers for more than a year. However, rather than negotiating in a back room, opposition pressure eventually forced the Government to put forward a formal amendment during the debate that created a new mechanism allowing MPs to vote every six months on whether to keep the powers in place. Australia's Coronavirus Economic Response Package Omnibus Bill was debated on the same day it was introduced, but it too was amended during passage after receiving more than three hours of debate in each chamber of the Parliament.

This is an important comparison, but one that doesn't have some additional context that colours the Canadian experience, which is the fact that given the evolving situation with the pandemic, the response came on the Friday before a constituency week timed for the March Break around much of the country. If there's one thing that we have seen repeatedly over successive parliaments is that there is an absolute reluctance in this country for MPs to extend their sittings into a weekend, let alone into a constituency week. While we occasionally have seen instances where senators will stay longer, the threat of having to sit on a Friday is fairly often wielded to get more cooperation within that chamber as well.

This is one of the biggest reasons why there was such a rush to ram the first emergency bill through the Commons (along with two Supply bills). At least with the Supply bills, there is some pre-existing chance for MPs and Senators to know what will be in those packages, but this was not the case with Bill C-12, where its contents were only made known through behind-the-scenes negotiation, and it was not even viewable by the public until after it received Royal Assent. The Samara report rightly calls this out, but the fact that it couldn't contextualize this important bit of information hurts their analysis.

Some of the other analysis in the report are unfortunately shallow and add nothing to the issue, such as counting up the fact that the proportion of women in the Chamber for the emergency recall for Bill C-13 to decry that it somehow affected the representativeness of the vote on that legislation, or the fact that most of the MPs present were from Ontario and Quebec which was intentional, because it was supposed to be for MPs who wouldn't need to travel by plane. In fact, in the report calling out that too many members of the respective parties' leaders and not enough backbenchers were represented ignored the fact that the government made a special deal with Andrew Scheer, as well as his House and Senate leaders, to be flown to Ottawa and back for the single-day sittings in each Chamber. The report also glossed over the extent of what happened with the proposed oversight committees in the Senate, which again does a disservice to the nature of how necessary oversight has been impacted by the state of affairs in the Upper Chamber.

In a separate summary to the report, Samara also advises Parliament to work out how to "go remote," which is the next klaxon for me as the Liberal House leader has written to the Speaker asking for advice on how to achieve some kind of virtual sittings of the Commons (which is a spectacularly bad idea).

Parliament must urgently identify ways to ensure that all MPs remain able to effectively represent their constituents and have their voices heard, including through technology-enabled engagement at a distance. We have already seen that the pandemic will impact different parts of the country in different ways. The ability of MPs to share such diverse experiences can help to improve Canada's response, and should not be sacrificed in the name of efficiency.

This particular suggestion is flawed in two respects one in that somehow MPs need to "share diverse experiences" rather than exercise accountability is troubling for an organization that is supposed to help Canadians better understand their parliament. The other is the urging of "technology-enabled engagement," which will be the death knell of our parliament if it actually happens. It doesn't matter that there is a global pandemic parliament is an essential service, and as such, needs to have a physical presence (a fact bolstered by the constitutional requirements around quorum). There are provisions that it can be run with a skeleton crew, and rather than get hung up on the exact representational dynamics as Samara seems to be (though parties could do so if they so choose), we should be more concerned with simply having enough MPs in place to do the work, and who can be seen to relay the concerns of their caucus colleagues from around the country as they do so. It would be great if Samara could be open to such possibilities as well, as opposed to simply counting heads.

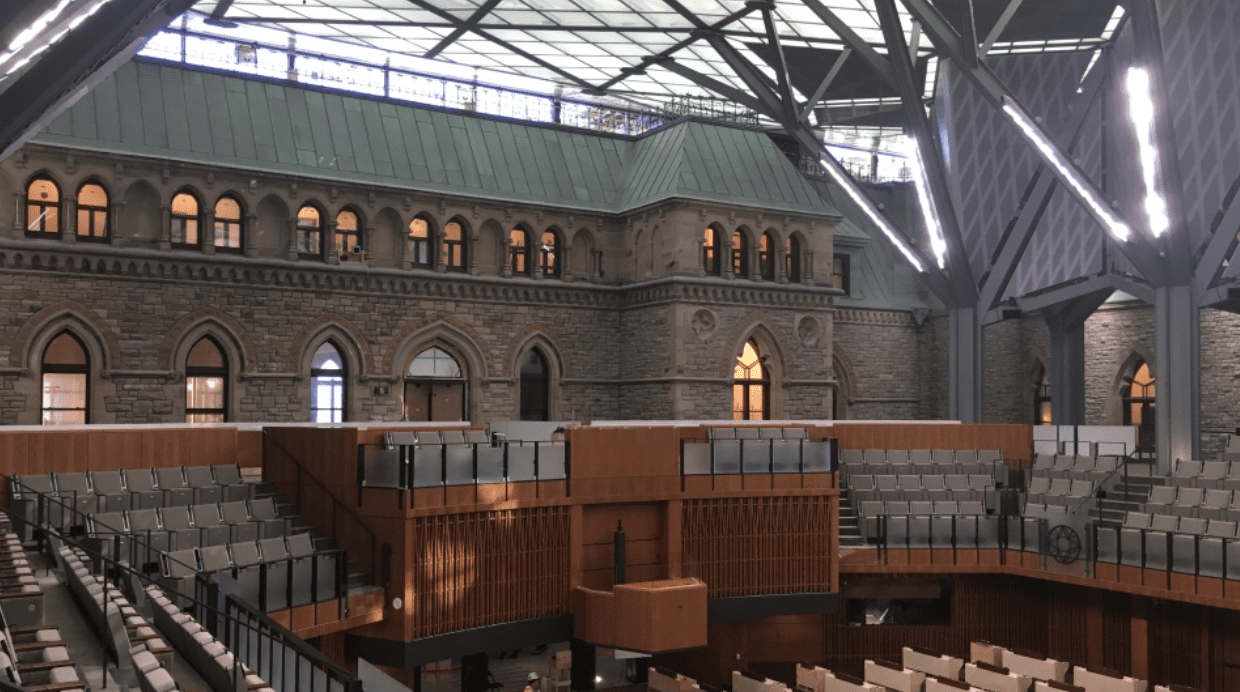

Photo Credit: CBC News