This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This content is restricted to subscribers

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

A worldwide virus pandemic, unprecedented in our lifetimes, has brought the global economy to its knees. For working-class Canadians already struggling with out-of-control housing costs and mountains of debt, the timing couldn't be any worse. Canada's social safety net, minuscule compared to many European countries, isn't sufficiently robust; nor will emergency support measures announced thus far come close to satiating need. Perhaps the only undertaking that would allow most Canadians to retain financial stability and peace of mind throughout the entirety of this pandemic is a basic income.

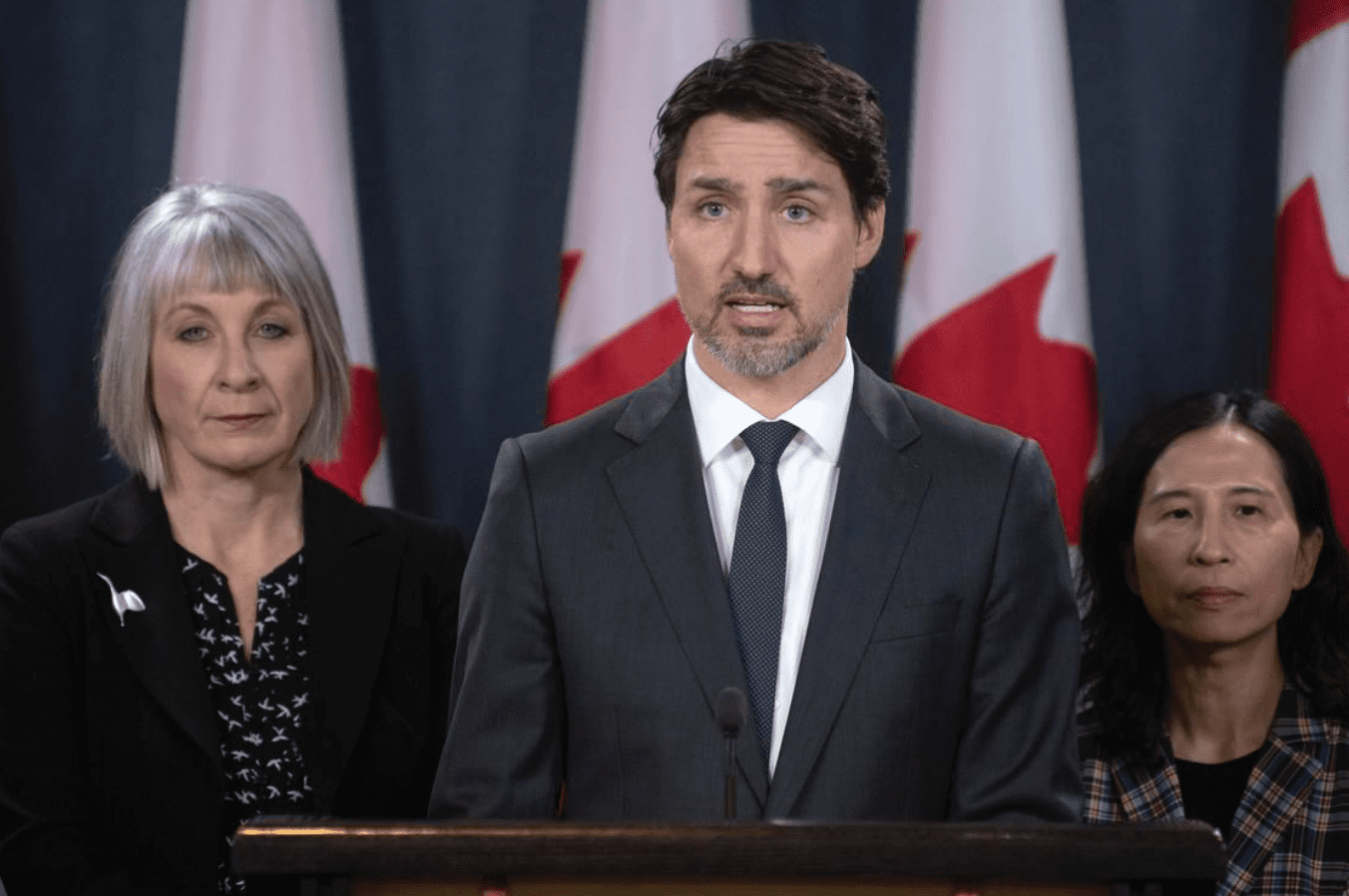

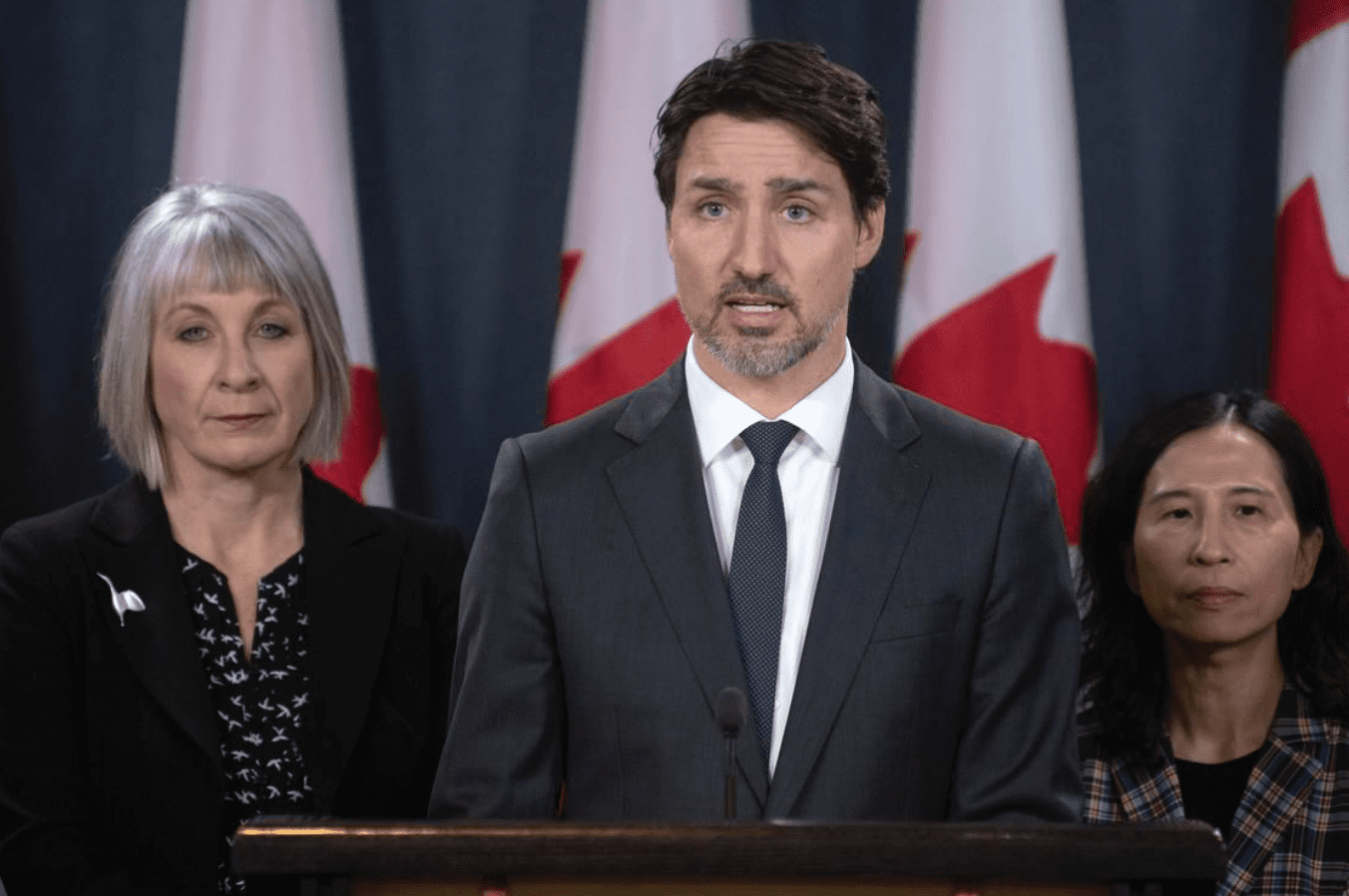

Officials in Canada have announced an array of remedies for the looming crisis. The federal government will offer a $27 billion aid package that includes money for those who acquire SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) or who leave work to care for sick family members ($10 billion), self-employed people whose earnings decrease ($5 billion), and Canadians on a low income ($5.5 billion). The usual one-week delay before applying for employment insurance has also been temporarily scrapped.

Provincially, British Columbia will offer $1,000 to people out of work due to the pandemic, while Ontario has suspended residential rental evictions and reduced electricity prices.

But these measures don't even come close to ensuring low-income people will be able to remain financially afloat in the months ahead. Employment insurance (EI) is only 55 percent of a person's normal earnings, for a maximum of $573 per week, and is capped at 15 weeks. Compare that to France, where such supports last a minimum of four months, and up to two years, or up to three years for workers above the age of 55.

Many Canadians who were barely able to subsist in precarious occupations during the best of economic times are now being offered a mere fraction of their former salary to cope with what could become the most severe recession of our lifetimes. With the cost of a one-bedroom rental in Toronto just shy of $2,250 each month, people wouldn't even be able to pay their full housing costs with EI, let alone food and other costs of living. And what happens if the economy is still in a shambles 15 weeks later when everyone's EI runs out? For many, welfare rates would be less than half of what they will receive under EI.

The Ontario provincial government has suspended residential rental evictions, but what happens if provinces already suffering from a housing affordability crisis such as British Columbia don't follow suit? April 1st risks becoming Black Wednesday, a day of humanitarian disaster rather than banal practical jokes.

Compounding matters for many working-class Canadians is that personal debt had already reached unsustainable levels prior to the onslaught of the global pandemic. Households have accrued $2.3 trillion in debt, according to the latest Statistics Canada figures, while 47 percent of us struggle to pay our bills even with a humming economy, according to insolvency firm MNP. Canadians reached the $100 billion milestone in credit card debt for the first time this past September, according to consumer credit reporting agency TransUnion. The same company had forecasted that the average Canadian's non-mortgage debt would rise to above $31,500 by the end of this year. And according to the National Post, Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz had already cautioned prior to the current pandemic that large household debt is Canada's greatest economic vulnerability.

With financial difficulty comes tremendous stress. Many organizations predict a surge in domestic violence and child abuse in the coming months. It will be more difficult than ever for the victims of abuse to flee to safety in the midst of a combination of pandemic and recession.

Productivity is also likely to wane among people theoretically able to continue working from home, as time is spent checking in with family and friends, as well as remaining abreast of daily news and financial support announcements. It's surprisingly tricky to focus on mundane work when the world is on fire.

But one solution could ensure that Canadians remain financially solvent, as well as reduce the anxiety related to uncertainty. A basic income would give enough money to each Canadian to ensure bills could be paid until the pandemic wanes and the economy improves. Would it prove expensive? Sure. But then again, it could serve as the financial bridge that prevents the economy a construct alarmingly based on emotion and irrationalism from catastrophic collapse. No money would be wasted, because people who continue to earn an income would remit back any superfluous funds back through the tax system.

Canada has already experimented with a basic income, and preliminary results were promising. The federal government gave the poorest residents of Dauphin, Manitoba, a "mincome" for several years in the 1970s. Before a subsequent Progressive Conservative government cancelled the trial, the small town saw its poverty reduced to zero, as well as people invest in occupational training they otherwise wouldn't have been able to afford. Hospitalization for physical and mental ailments both declined. Most people did not stop working despite the guaranteed boost to their income. Instead, they improved their lives.

The Province of Ontario recently also ran a basic income pilot in three communities, until it too was cancelled by a Progressive Conservative government in 2018. Recipients reported improved self-esteem and mental health, fewer trips to the hospital, decreased use of tobacco and alcohol, improved diet, as well as better housing security. Many participants acquired jobs or used the stable financial foundation to start a business.

Would a basic income be perceived by politicians more favourably under the current pandemic? Experts from across the political spectrum including Hugh Segal, a former senator and advisor to Prime Minister Brian Mulroney were already promoting the idea of such a government program prior to the worldwide SARS-CoV-2 outbreak.

But more interesting are the surprising names now floating the idea of a temporary, emergency basic income to alleviate economic distress from the pandemic. These include Ken Boessenkool, a former adviser to Prime Minister Stephen Harper and previous lobbyist for Enbridge not an archetype that would typically wave the flag of socialism.

If a basic income can keep a roof over many Canadians' heads, and give the economy the confidence to make a much quicker rebound, it's possible that such a program could pay for itself, despite the high costs involved. And there has never been a more opportune time to procure support from the political right for such a bold and controversial venture than now.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.