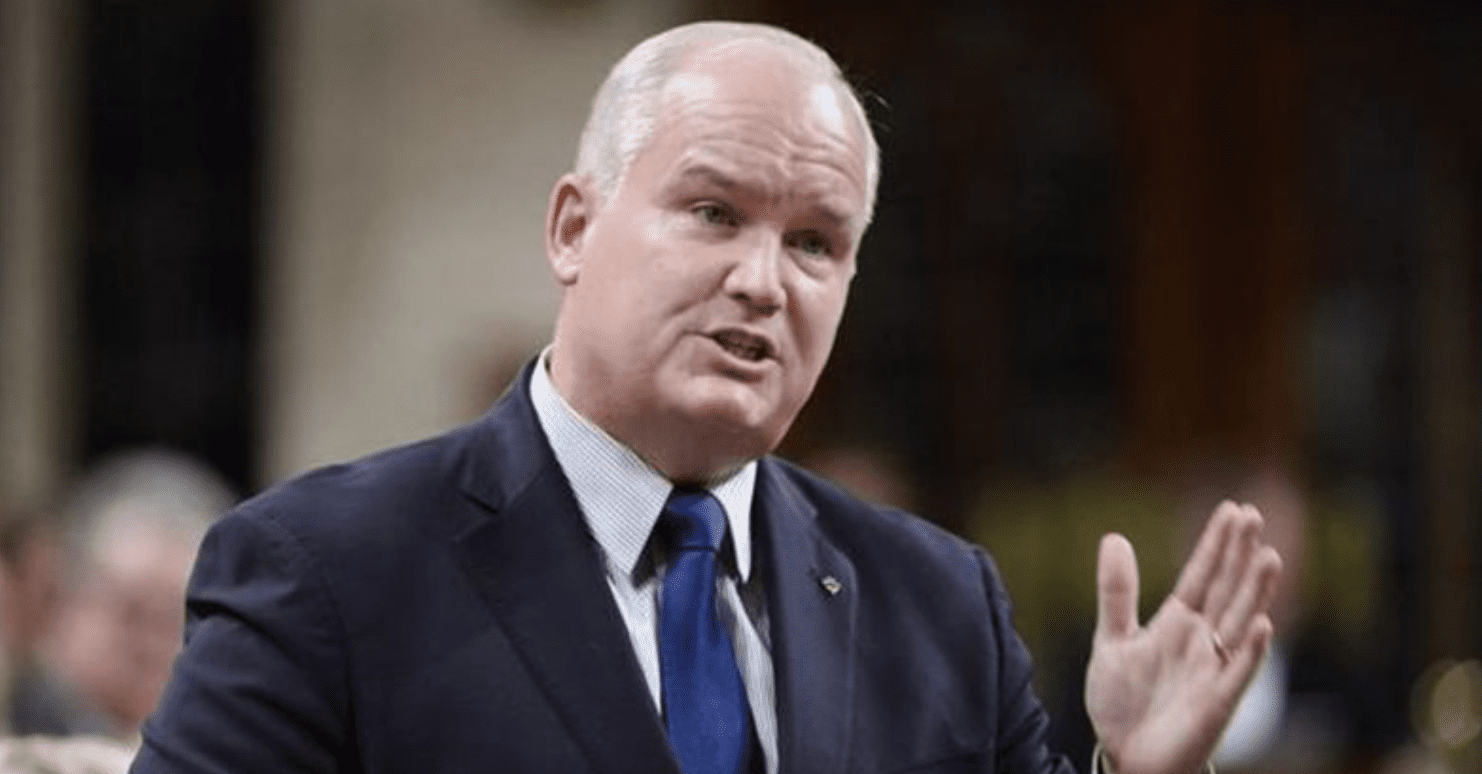

In an interview over the weekend, putative Conservative leadership candidate Erin O'Toole opined that Canada needs fewer "lifers" in politics justifying that he isn't one, and by inference is throwing some shade at other "lifers" such as Andrew Scheer and Pierre Poilievre, who went directly into political life at a young age and haven't really had any experience outside of it (unless you count Scheer's six months as an office clerk in an insurance firm).

"I'm not a career politician," O'Toole stated in the interview. "I think Canada needs more doers in politics and less lifers, and that's going to be part of the discussion."

O'Toole, however, is dead wrong about this. At the federal level, Canada is already a country with an unusually low rate of incumbency in the House of Commons. We already have a very high rate of turnover among MPs, and this in turn means that there is a deficit of institutional memory in the lower chamber, which can make for poorer decision-making and a loss of necessary perspective. To an extent, we compensated by means of the Senate, where the major parties would have a great deal of their institutional memory invested both for Parliament as a whole, and for the caucuses themselves but with prime minister Justin Trudeau's insistence on banishing senators from his party's caucus, and appointing independent senators with little to no political experience, we are already losing that particular repository as well.

The sentiment behind O'Toole's rhetoric is fairly common in Canada, even if instances of "career politicians" are exceedingly rare in the broader scheme. There is a particular fetishism for those who have had business success to go into politics in this country and indeed, the Conservatives tried to make a great deal of hay about the fact that Trudeau had never had to make payroll during the 2015 election (which was funny because neither had Stephen Harper, nor did Andrew Scheer when he became leader). When I recently got a call from a polling firm doing a survey on the Conservative leadership contest, a great many questions were about whether or not I, as a voter, would have a more favourable opinion of someone who had success in business and wealth from said business success than someone who had been in politics a long time, including with some fairly loaded language around preferring an "outsider" with business success to someone with political "baggage." This is clearly in the minds of those who are trying to determine what the party needs going forward if they want to win the confidence of Canadians.

O'Toole draws on his career in the military as a navigator in the Royal Canadian Air Force, as well as a time spent doing corporate law, to prove his credentials as not a "lifer," but doesn't seem to put any particular credence to the fact that those may not always be skills that prepares one for a life in politics there are some particular social skills that people who excel at politics may possess that those in other fields simply have a hard time grasping, which is why some particularly brilliant people can have a difficult time in political life something I think we've seen a great deal of in this country.

If we look across the pond to Westminster, there is a greater culture of political "lifers" within their own House of Commons, which has made for a few different dynamics in how their political culture plays out as compared to ours. Part of this has to do with the fact that they have nearly twice as many seats as we do, which has increased the number of "safe" seats in their Commons, which allows for some members to enjoy long parliamentary careers, and that can lead to some greater independence their backbench rebellions can happen as a result of this assuredness that these MPs will likely still win their seats even if they find themselves punished by their party leaders for stepping out of line.

But the "lifer" culture in Westminster extends beyond just "safe" backbenchers who know they'll never make it into Cabinet and can play the role of being a good parliamentarian regardless it also extends to former ministers. There is a more accepted culture in Westminster of former ministers hanging around the Commons for years after their time in Cabinet, and becoming subject matter experts for Parliament to draw upon. We see very little of this happening in Canada far too often, we see former Cabinet ministers (or sometimes even current ones who have been in office for a while and who can see their government getting a bit long in the tooth) decide that it's time to go seek greener pastures, and get their hands on some of that sweet, sweet corporate dough, making the kind of money that is pretty much impossible to do within Canadian politics, particularly given how much ethics rules have tightened up in recent decades. It also gives one a sense of how little we value people in politics that we nurture the sense of righteous indignation about the salaries that our elected officials make which is often far less than they would make in fields such as law that those former ministers feel compelled to leave politics for money.

Given his apparently dislike of long-time political experience, I have to wonder what this signals for O'Toole's intentions to stay in public life if he doesn't win the Conservative leadership. I also have to wonder about the attitude that "lifers" can't be "doers," or that somehow the work of a long-time backbencher doesn't have value, particularly if they have been a good parliamentarian and have been playing the role of accountability that they're supposed to. If anything, I fear that O'Toole's sentiments betray a lack of understanding about how politics should be practiced, and instead focuses on the toxic stereotypes that poisons the well for those who would devote their lives to public service. There is nothing wrong with a "lifer," and we need more of them in our parliament.

Photo Credit: The Canadian Press