As part of his farewell tour in the media over the past week, Leader of the Government in the Senate, Senator Peter Harder, opined that the Senate's ethics rules need a rewrite because of how long it took for there to get any kind of answers as to the complaints regarding former Senator Don Meredith. While nobody will dispute that the length of time to complete the investigation and come up with a report was on the outer bounds of what should be acceptable, this was no ordinary case, and the Senate is no ordinary workplace, particularly when the alleged harasser is a senator. While it may be fair to wonder what kinds of rules could be put into place to try and ensure speeder results, we should first take a step back and get some more perspective on the situation and what is being demanded of it.

One of the questions being posed from the start is whether the Senate Ethics Officer should be a full-time position, given that it is currently only part-time and the SEO is paid on a per-day basis. In order to get a sense of why this is the case, we need to first remember that the Meredith case is out of the ordinary when it comes to the day-to-day activities of the SEO. Most of those activities relate to ensuring that newly appointed senators comply with the rules when it comes to what kinds of assets they hold, and for things like work on corporate boards. After all, senators are eligible to take positions on corporate boards, and it used to be common practice for corporations to have a senator on their board as a kind of prestige appointment. Changing corporate culture, however, is changing and a stronger focus on governance means that boards are now expected to be more robust in their duties and activities, and there is less incentive to have these kinds of prestige appointments not to mention that the corporate board work is now more time consuming, meaning it's less attractive to senators who already have fairly busy schedules. It would make no sense to have a full-time SEO merely for the sake of investigations that may or may not happen.

The other reason why it's hard to demand rule changes based on the Meredith case is the fact that there were no actual formal complaints filed by any of Meredith's former staff. The investigation began after the former Senate speaker noticed a high volume of turnover in Meredith's office and looked into why. It's hard for the SEO to investigate when no formal complaint has been filed. He is also hampered by the fact that senators themselves were slow to respond to requests so much so that he went ahead and sought permission from the Internal Economy Committee to access those senators' private emails, which created a stir when this was found out. The fact that this happened shows that the SEO already has more power than most senators thought he did, so I'm not sure why there is a move to give him even more powers.

There are a couple of different underlying problems here, which Harder and certain other newer senators who are also loudly demanding these kinds of changes don't appreciate because they haven't been in the Senate for very long. One of them is the fact that, much like the House of Commons, there has been a move away from the previous way of dealing with these kinds of issues, which was to have the party whips deal with situations as they arose. Because there wasn't a formal process, the whips could often offer an approach that was more akin to mediation and even restorative justice once alerted to the situation, but this has proven to be problematic for the newer generation of MPs and senators, which is why new complaints mechanisms and processes have been developing.

At the same time, we have seen a shift in how discipline is handled, which is that at the first whiff of trouble, an MP or senator is swiftly removed from caucus either "voluntarily" or otherwise until the matter is dealt with. This winds up removing the ability for whips to do the problem-solving, mediation or restorative justice that used to be done, leaving it to outside bodies to handle, whether that's the new complaints process, or someone like the SEO. This is another change that has not been for the better MPs and senators have been very quick to turn over more power and responsibility to officers of parliament rather than dealing with the problem themselves, like they're supposed to. Part of this is the ongoing slide that has been happening in Parliament for decades, but part of it is the optics challenge, where people media voices in particular get huffy when they describe how parliamentarians set their own rules and enforce them, not understanding that it's because parliament is self-governing and needs to be (lest we simply turn everything back over to the Queen). It also fails to understand that Parliament is not an ordinary workplace, and MPs and senators are not middle managers.

Changing the rules won't change the underlying culture of a place that is not an average workplace. There are career implications for filing complaints, particularly because senators or MPs can't be "fired" as though this were a corporation. The process for their removal for cause have high bars, necessarily so, and I'm not sure that Harder or the other agitators quite get that. I also suspect that this is part of Harder's attempt to swoop in and play hero on his way out the door, and looking like he's making changes to an institution that has been maligned in the public eye (not always undeservedly). But when you look at the broader context of the situation, it looks an awful lot like he's looking to make changes for the sake of making changes, which is a poor way to deal with an institution like parliament where the probability of unintended consequences is very high indeed.

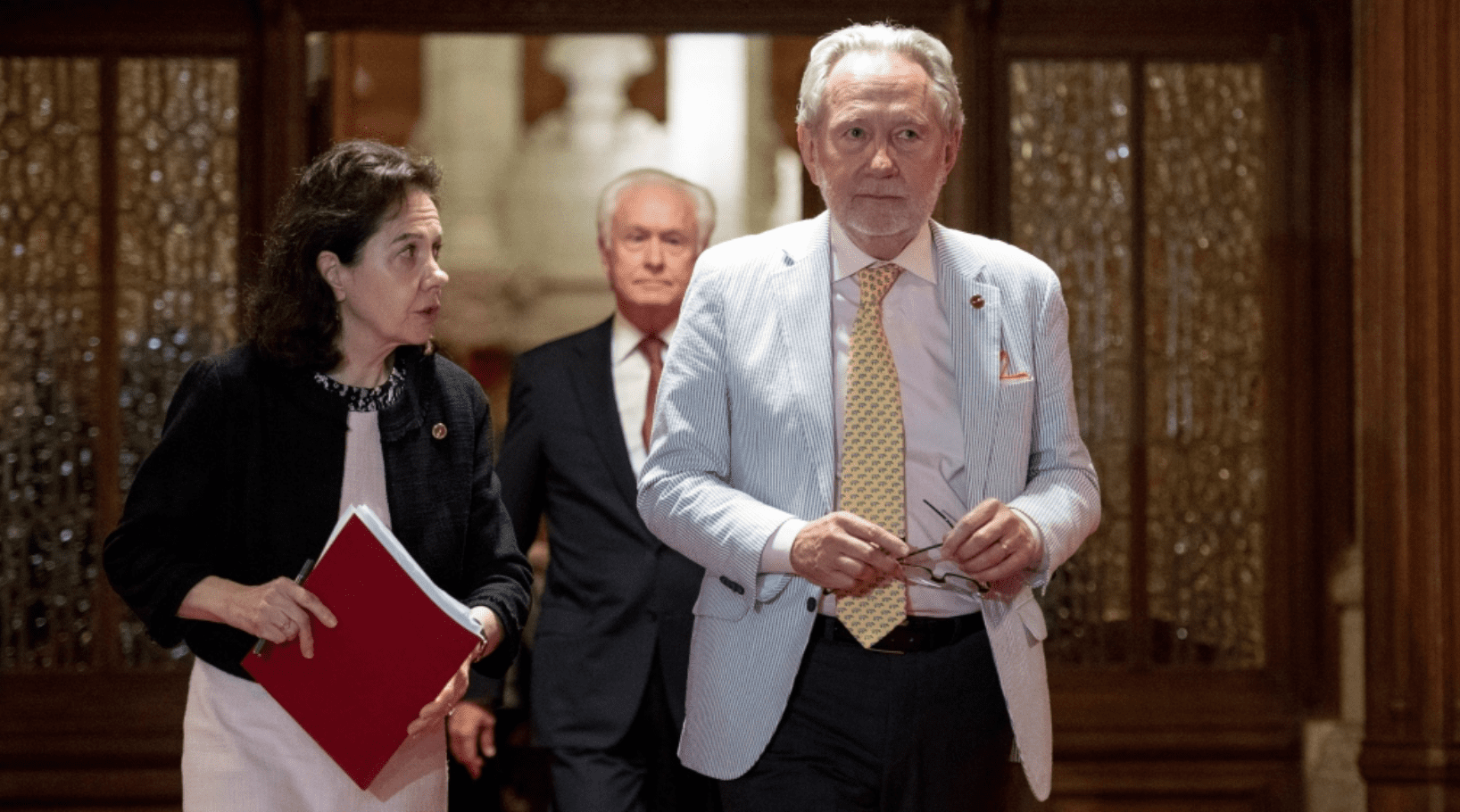

Photo Credit: CTV News