De-indexing: what an innocuous word. In provincial budget terms it sounds far less threatening or extreme than cutting, slashing, reducing or eliminating.

But there's always some spoil-sport economist or opposition critic who does the math and sounds the alarm that de-indexing does, in fact, equal a reduction over the long haul.

The recent Alberta budget, still toiling through legislature debate, applies de-indexing to Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH). The support payments, a basic benefit of $1,685 per month for those who can't work because of their disability, will remain the same in 2020, with no increase for inflation, and there is no fixed date to reindex the income.

In 2019-20, the measure will save the government $10 million. But it will cost severely disabled recipients in real monthly purchasing power in ever increasing amounts $35 next year, $65 the year after that, $100 the year after that, according to calculations from University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe.

In the grand scheme of things $10 million isn't much in terms of $47 billion in program spending. But this particular bean counting measure, directed at the most vulnerable of recipients, costs considerably more in political capital.

Just ask the Ontario Conservatives about what happens when you tinker with support funding for a group like families with an autistic child. You get bludgeoned by protesters and the opposition and any kind of defence for the measure just digs you deeper into the mire.

Take a recent op-ed by Rajan Sawhney, Alberta's minister of community and social services.

"To ensure long-term sustainability of the AISH program, the least detrimental measure to current program recipients was to pause indexing… Alberta's AISH rates remain the highest among the provinces for people living with a disability ($400 more than the second-highest province, Saskatchewan)," argues Sawhney.

A comparison with inadequate funding for the severely disabled in other provinces is a losing argument. That $1,685 per month is simply not much to live on, especially given the challenges disabled recipients face. It's an easy to understand number for those managing a household budget.

Facing a future without the assurance your income will keep up with inflation (it is called Assured Income, after all) has advocates and clients speaking out about promises broken by the UCP. And they are speaking up in terms of paying their heating bill or putting dinner on the table.

The opposition has been all over the issue. And the comparison they make isn't to other provinces but to calculations in the budget. Specifically they are arguing that the UCP is taking money from the vulnerable to give corporations a $4.7-billion tax break.

The UCP dispute that figure, which all members of the NDP practically chant in unison every chance they get. The four per cent reduction over four years in the corporate tax rate won't add up to nearly $4.7 billion the government argues. However, that defence has a whole lot less emotional resonance than the relatively small sums in the AISH de-indexing policy.

Opposition Leader Rachel Notley showcased the issue at a media conference this week with a backup from several recipients of AISH who voiced their fears about the effect of de-indexing. Real people with real needs make for compelling politics.

Any government spending with that sort of emotional freight should carry with it a premium multiplier when budget decisions are being made. Every dollar cut from programs for disabled and disadvantaged members of society is worth at least 10 times that amount in the reputation hit for the government.

In Ontario the Progressive Conservatives have had to walk back their autism support program policy. Alberta's government needs to take a hard look at the human and political cost of the economies it is imposing on AISH recipients.

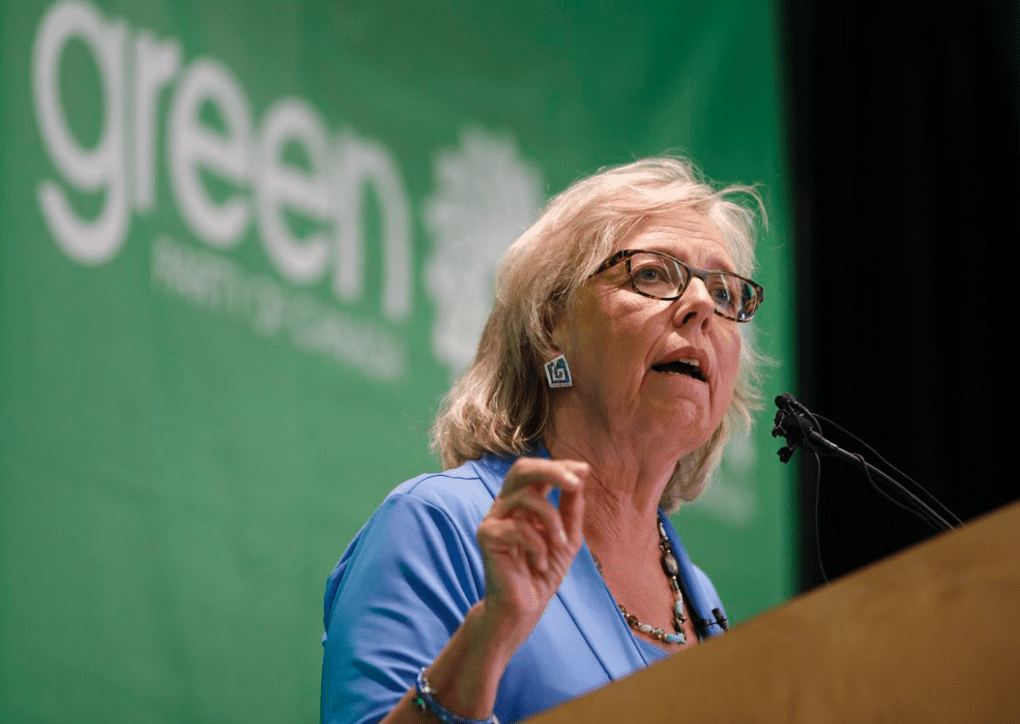

Photo Credit: Jason Franson, The Canadian Press