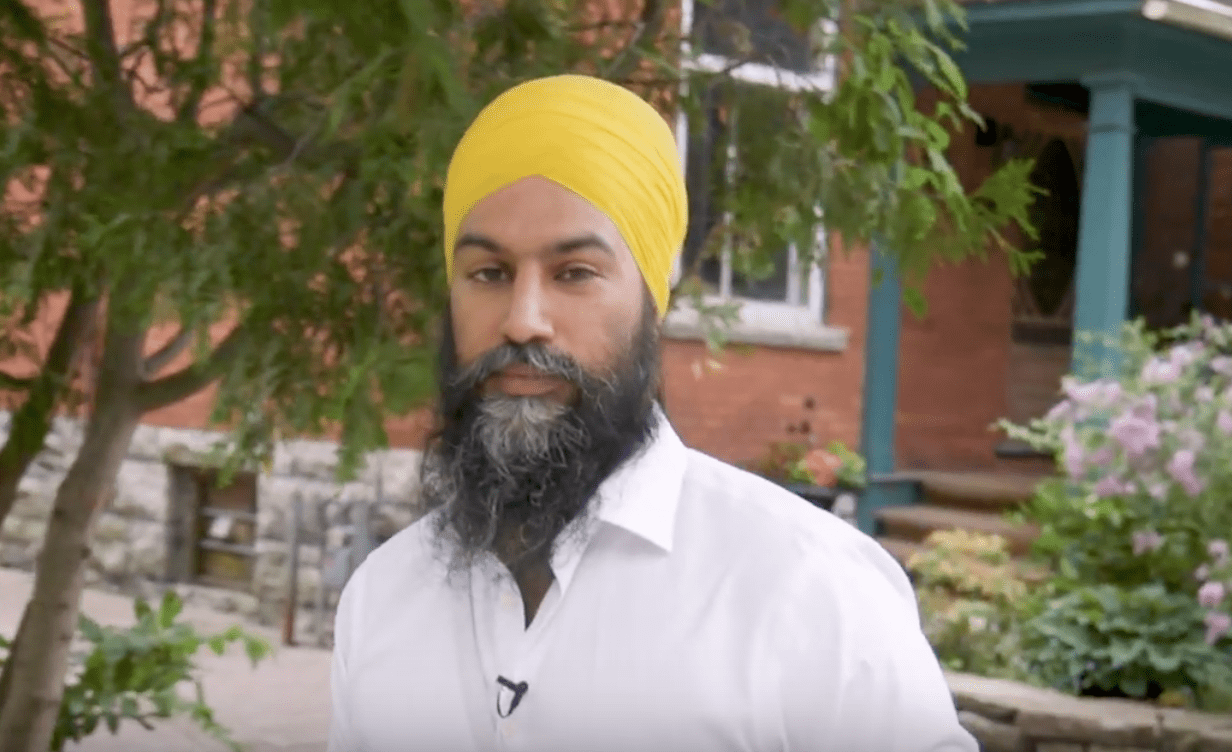

"…[I]f the other parties work with us, we have an incredible opportunity to make the lives of all Canadians so much better."

—NDP leader Jagmeet Singh

"The Bloc Québécois can collaborate with any government. If what is proposed is good for Quebec, you can count on us."

—Bloc Québécois leader Yves-Francois Blanchet

"Divide and conquer."

—Philip II of Macedon, 4th century BCE (and possibly Liberal strategist Jeremy Broadhurst)

Jagmeet Singh and the federal New Democratic Party knew a hung parliament was on the horizon. A rare opportunity for the NDP to obtain power loomed. Although the party wasn't on course to repeat its heady 2011 achievement of forming Official Opposition, something even more enticing awaited: a minority government, and the negotiating leverage that comes with it.

But unfortunately for New Democrats, the Bloc Québécois largely disregarded since its 2011 electoral collapse ballooned in popularity just two weeks before election day, achieving its largest level of support in public opinion polls in six years. And thanks to Canada's archaic voting system, the NDP ultimately received fewer seats than the Bloc, despite earning more than double the Bloc's national vote share.

This result elevates the Bloc to suitor of a Liberal minority government (assuming a coalition is highly unlikely), giving Justin Trudeau another potential collaborator for surviving confidence votes. Because the Liberals have the choice of working with either the NDP or the Bloc, the NDP's negotiating power for acquiring policy concessions from the Liberals may be greatly diminished. For example, if the New Democrats were to demand electoral reform as a requirement to support a Liberal budget, Trudeau could instead turn to the Bloc to get the votes he needs.

Liberal negotiators will undoubtedly exploit this as a strategic tactic during pending party negotiations. This is likely to cause both the NDP and the Bloc to curtail their demands in the hope of being chosen as the Liberals' governing dance partner. The Grits will also likely choose informal cooperation rather than a formal confidence and supply agreement as seen provincially in British Columbia, as the party will want to keep its options open and play the opposition parties off each other for as long as possible.

Trudeau will have little choice but to acquiesce, at least to a moderate degree, on policy areas that find broad agreement between New Democrats and the Bloc: more aggressive action on climate change and increased funding for social programs. But on some opposition demands, such as proportional representation from the NDP or increasing xenophobia in Quebec from the Bloc, the Liberals hope diminished opposition leverage will give them the upper hand to reject both.

If there is no formal coalition or confidence agreement, the Liberals could rotate between NDP and Bloc support as needed. The smart money is on the Liberals opting to cooperate with the NDP more often than not. Although both New Democrats and the Bloc have expressed an interest in working with a minority government, the Liberals would find the NDP a far more palatable sidekick. Working with the Bloc could make for uncomfortable optics; Conservatives would surely attempt to paint the Liberals as "submitting to sovereigntists," despite that the Bloc went out of its way to avoid evoking sovereignty this election.

A deal with the Bloc that secures increased social program spending primarily in Quebec, rather than for all of Canada, would be of limited use to voters outside la belle province, and could heap scorn on the Liberals unless money is more evenly sprinkled across the country.

Ironically enough, the Bloc's resurgence may be of benefit to voters outside Quebec at least for those who desire a stable hung parliament that works effectively and avoids an early election. The more dance partners the Liberals have, the more likely the government is to acquire the confidence of the House of Commons and avoid an unexpected collapse.

Progressives outside Quebec may ultimately be disappointed by the resulting policies, as the opposition parties' decreased leverage will likely result in a more centrist government. Even on matters the NDP and Bloc agree on, such as climate and social spending, the Liberals may be able to minimize concessions.

Even muted versions of NDP or Bloc policies, however, would require higher spending by a Liberal government already on the defensive about deficits. Would the Grits opt to fund such spending by increasing deficits beyond projections in their platform, at the risk alienating centrist and Red Tory voters? Or would the party instead be willing to generate additional revenue by increasing tax on the wealthiest members of society, as both the NDP and Bloc have advocated? Neither would be a comfortable choice for the business-ensconced Liberals.

Strangely enough, the NDP will prove far more powerful in 2019 with only 24 seats than it was back in 2011 with a whopping 103 seats, due to a hung parliament. Yet it must still sting for New Democrats that their expected opportunity to shine risks being eclipsed or entirely superseded by a renascent Bloc Québécois.

Photo Credit: National Post