Last week, there was no shortage of pearl-clutching and running for fainting couches as Conservative leader Andrew Scheer reiterated his long-held position that if he should form government, he would return to the former mode of making partisan appointments to the Senate. The horror! This caused an immediate flurry of tweets from the likes of Senators Peter Harder and Yuen Pau Woo, and a few of the academics who have become invested in this "independent" model of the Senate, despite the fact that what Justin Trudeau has proposed and attempted to implement is a rather blinkered version of what role the Senate is supposed to play in our parliamentary system. Scheer's plan to return to partisan appointments is undoubtedly the right one within limits. It can also backfire and become just as problematic as the damaged state that the institution found itself in by the end of the Harper era because of the improper way in which those appointments were handled.

Despite what Harder, Woo, and even Trudeau himself are saying, the new era of "independence" in the Senate is not actually working, in large part because it was done in a ham-fisted and haphazard way, in complete ignorance of how the Senate operates and is supposed to operate. Independent senators were appointed without any consideration about how to train them to be senators, which the political caucuses would normally do, and when they started organizing themselves with the help of a couple of established senators who had since declared themselves independent (Senator Elaine McCoy was ostensibly an independent after the rest of the Progressive Conservative caucus aged out), a few of them started developing some very poor habit and beliefs things like the absurd notion that horse-trading was somehow "partisan" and therefore off-limits, rather than simply the way things get done in a political institution.

The result of this new way of doing things? Delay, mostly, as the Independent senators can't organize themselves enough to keep legislation moving, which is exacerbated by a refusal to do the hard work of negotiation, or to adhere to agreements that are struck. They point to all of the amendments to bills that went through, but conveniently forget to mention that the vast majority of those amendments came from the government and were simply laundered through the Independent senator who was "sponsoring" the bill (which they absolutely should not be doing). And because things aren't moving through the Senate with any efficacy, it's causing Harder and others to start proposing very problematic "solutions" like the forced time allocation on all Senate business you know, rather than doing their actual jobs and negotiating with one another.

So would partisan appointments bring things back to a better state of affairs in the Chamber? Maybe, if they're being done properly, and if Scheer is committed to doing them, then we have to ensure that we won't simply see a return to what Stephen Harper did, which caused its own harm to the institution. By first refusing to appoint "unelected" Senators (unless it was politically expedient *cough*Michael Fortier*cough*) Harper allowed a huge backlog of vacancies to accumulate until the 2008 prorogation crisis, at which point he suddenly became afraid that the proposed coalition would appoint Elizabeth May to the Senate, and in a panic, he appointed eighteen senators nearly one fifth of the Chamber in one fell swoop, without proper vetting to see that some of them were even eligible to sit in the province they were appointed it (Senator Mike Duffy), and extracting the promise that they would support his Senate reform agenda and only sit eight years (something virtually all of them ignored). More importantly, however, was the fact that they were appointed under the expectation that they were to be whipped, which was not how the Senate had operated in nearly all circumstances for the vast majority of its existence. Without enough pre-existing Conservative senators to push back against this blatant abuse of power, it created a cohort of partisan senators who acted more like backbenchers than they did senators which was a problem.

A false notion has been floated by apologists of the current attempt at "reform" that the Senate was supposed to be non-partisan. It's not true it wasn't supposed to be able to thwart the will of the elected Chamber without sufficient cause, but more to the point, there was an intention that the Senate was supposed to have maintained a partisan balance rather than simply swamping it with partisans from one party or another. The fact that they are partisans is part of the role that the Senate plays when it comes to maintaining the institutional memory of Parliament. With a House of Commons like ours that turns over its membership at a much higher rate than other comparable democracies, it is especially important that the Senate hold that role both in Parliament as a whole, but within the party caucuses as well. Severing that institutional memory only solidifies the power of the leader over his or her MPs, which the Liberals are only now realizing and what the cheerleaders of these "reforms" are ignoring.

And this notion of balance is what any future prime minister (or even the current one, should he be able to admit that he was wrong about these quixotic "reforms"), should strive for going forward. There was a brief moment in the last parliament where the Senate maintained a rough balance between the Conservative, Liberal, and Independent caucuses, and that is something that we should strive for going forward a mix of partisans with enough cross-bench Independents to ensure that the power dynamic of the duopoly remains broken so that the abuses that it engendered stay buried. But that will mean swallowing pride, appointing Senators that are not only partisan but also partisan of the opposite stripe in order to keep the balance intact. We'll see if Scheer is capable of such an action, but if we want the Senate to function the way it was intended to, then it means leaders will need to do the right thing.

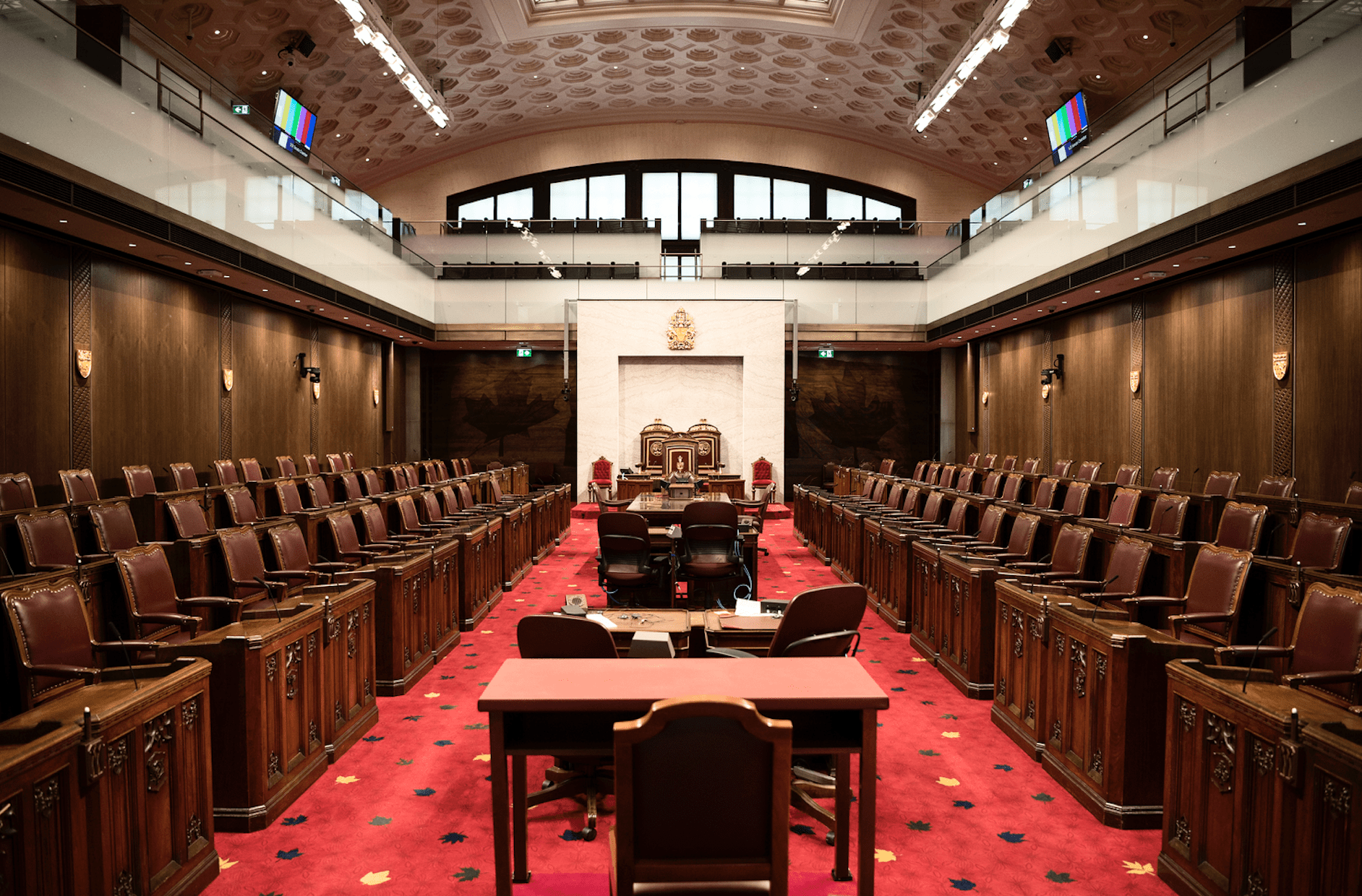

Photo Credit: Senate of Canada