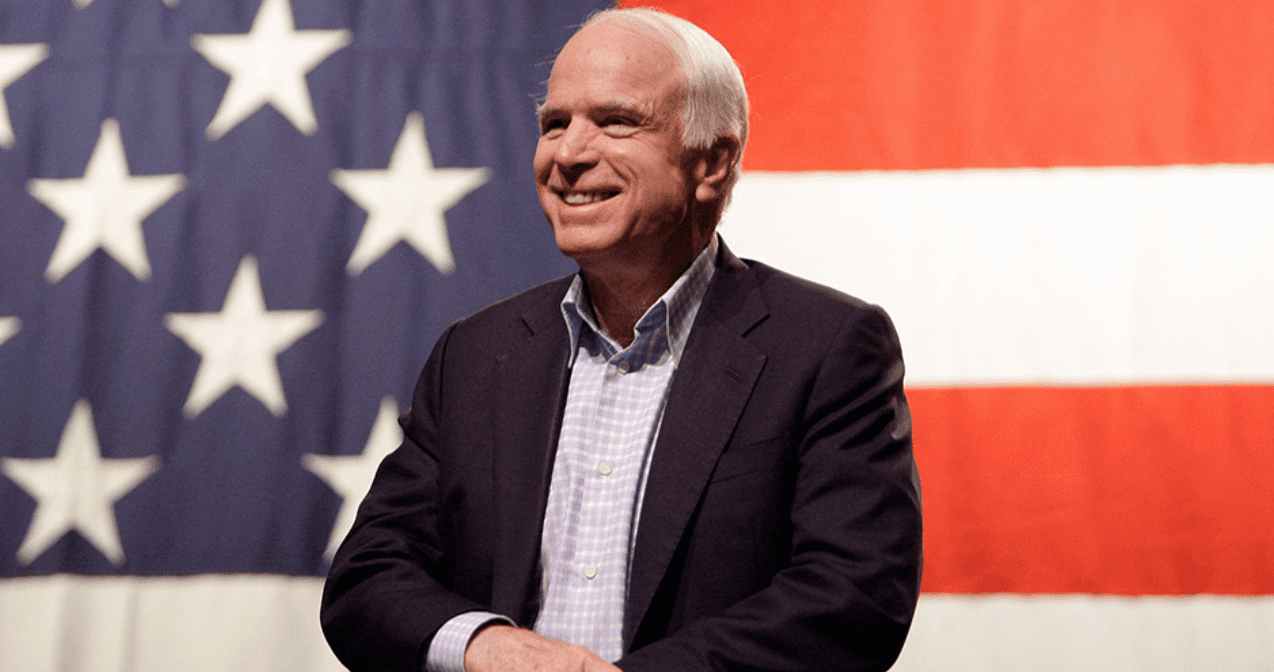

Nihil nisi bonum is the rule for the recently departed. So when I say Senator John McCain was a pain in the neck, I mean it in a good way. Whatever his failings, he stood up for what he believed in. And we need more of that kind of irritation.

If informed that he had annoyed me, I'm sure Senator McCain would have said "Who?" But he often annoyed presidents and colleagues and was not in the least embarrassed. Instead he reveled in his role as a gadfly.

I shall have little to say about McCain personally. Doubtless he had moments the eulogist does not dwell on, for most of which he took full responsibility. But he also inspired love and admiration in great quantities and will be missed including, remarkably for a man who died at 81, by his mother. (And the girl he and his 2nd wife adopted from a Mother Teresa orphanage in Bangladesh after bringing her to the U.S. for medical treatment.)

The various distinctions of his military career including a Bronze Star were overshadowed by the horrendous treatment he endured as a POW with courage most of us can only hope we might possess some of in such a situation. But my point here is to evaluate McCain the politician and neck pain.

What made him commendably annoying was mostly his resistance when urged to go with the flow. I do not agree with everything he stood for, particularly restrictive campaign finance laws; I believe the U.S. Supreme Court was not merely technically but philosophically right when they said in essence the state may not tell free people how they can spend their money to express opinions on public matters. And McCain could be snarky in the middle of a political fight or on losing one. But he did not tend to hold grudges or inspire them.

McCain was also applauded as a maverick partly because he tended to annoy Republican presidents and colleagues. It is remarkable how often liberal commentators' favourite conservative is not conspicuous for holding recognizably conservative beliefs on almost anything. But McCain was not in that category.

He was a deficit hawk and opponent of pork-barrel politics. I think his support for the line-item veto was, again, misguided, even unconstitutional; the separation of powers clearly gives Congress, not the president, the power and responsibility for budgeting. But I applaud his determination to fight this scourge of democratic politics. (And while I'm discussing the Constitution, McCain voted for two of Clinton's Supreme Court nominees on the grounds that "under our Constitution, it is the president's call to make." If only both parties were more willing to take that view today.)

McCain was also a hawk in the classic sense, a staunch supporter of national defence whose dissents in this area tended to be against missions lacking clear goals or exit strategy. Sometimes his stance appeared to give aid and comfort to political adversaries opposed to a robust foreign policy generally. But he didn't care; if he thought something was wrong he said so including Reagan's deployment of marines to Lebanon that ended in a horrible barracks bombing, and Clinton's PR-driven deployment of troops to Somalia that ended in national humiliation. McCain's painful awareness of what soldiers risk when deployed may have helped hone his sense of caution about vague military ventures. But mostly he was hard-headed about the use of power even when others were fuzzy.

Sometimes his "maverick" character made it hard to be sure what he stood for. I was in Manhattan during the 2000 Republican primaries in which McCain lost an early lead to George W. Bush, and at one rally the band backing him pumped out a song whose only lyrics were "John McCain" which I found revealing. There were rumours in 2004 that John Kerry might ask him to be the Democratic vice-presidential nominee. But if his 2008 campaign lacked ideological focus, it was generally characterized by a civil tone. And in 2009 he led opposition to Obama's stimulus package saying it cost too much and did too little.

He was no friend of Donald Trump, a point on which opinions may be divided. But he was so hated by the Russian government that when he died a member of the foreign affairs committee in the upper house of the Federal Assembly said "The enemy is dead" while a pro-Kremlin academic prominent on social media openly wondered how to replace him as a hate figure. If he annoyed Vladimir Putin that much, we should all admire his capacity to be a pain in the neck.

His unbending devotion to public service and to what he thought right over partisan expedience were the qualities we who did not know him will most miss.

John McCain, RIP.