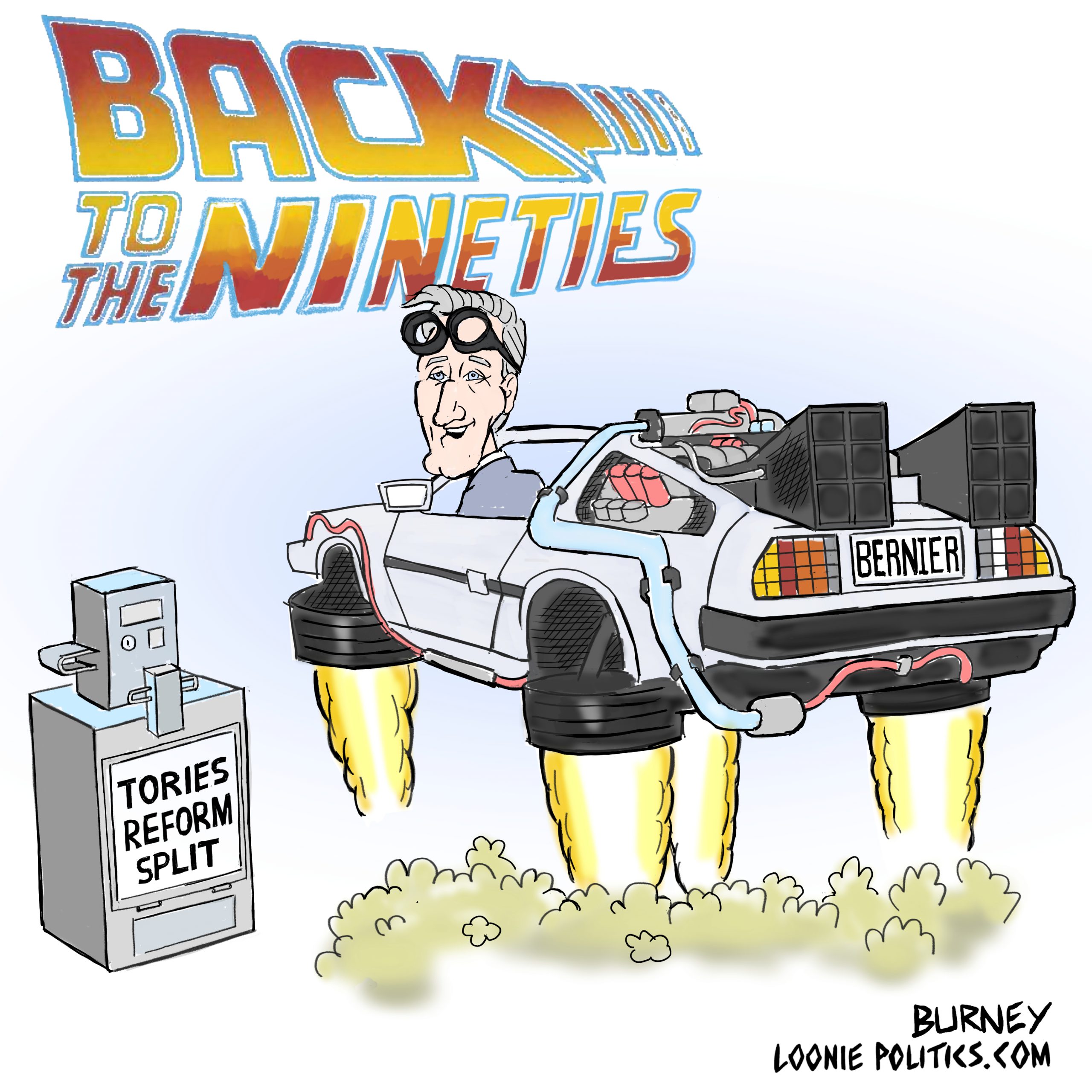

When looked at in isolation, Maxime Bernier's recent decision to abandon the Conservative ship so he could create a "Maxime Bernier Party" seems like a shocking and bold move.

Yet, take a step back to consider it from a more historic perspective, than Bernier's gambit could actually be seen as just the latest development in the Canadian conservative movement's chronic identity crisis.

Simply put, conservatives have trouble agreeing on what it means to be "conservative."

Indeed, it's much easier to find something conservatives all hate, than it is to find something they all love.

This is why, for a long time, the existence of the Soviet Union actually helped to create an artificial sense of conservative unity.

After all, for right wingers, the Soviets were the "common enemy" since basically anyone who self-identified as a "conservative" hated communism.

Yet once the Soviet Union got tossed into the dustbin of history and the fear of communism consequently subsided, conservatives lost that unifying glue and started to focus on the ideological differences that separated them from their "right-wing" brethren.

As a result, by the early 1990s, ideological tribalism began assert itself within the Progressive Conservative Party.

Libertarians within the PC party discovered they didn't like social conservatives, social conservatives didn't like Red Tories, Red Tories didn't like populists and populists didn't like libertarians.

Eventually (and perhaps inevitably) this ideological schism led to a massive political migration, as a loose alliance of fiscal conservatives and populists and social conservatives, who were all fed up with wishy-washy nature of Red Toryism, quit the PCs and joined the newly established Reform Party.

Since both the PCs and the Reform Party (later renamed the Canadian Alliance) each claimed to represent "true conservatism," a savage "right wing" civil war erupted.

Something similar also occurred in Alberta, when a disaffected group of libertarians and social conservatives broke off from the Alberta Progressive Conservative Party to form the Alberta Alliance Party and the Wildrose of Alberta Party, which later merged to become the Wildrose Alliance.

Interestingly, in due course, dogmatic infighting also erupted within the Wildrose Party; in fact, in 2014, its then leader, Danielle Smith, along with nine of her MLAs, defected to the Alberta PCs.

So yes, a conservative breaking away from a conservative party is something of a theme in Canadian politics.

Mind you, the internecine bloodletting amongst right-wing tribes at the federal level came to an apparent end in 2003, when the PCs and the Canadian Alliance joined forces to become the Conservative Party of Canada.

I say the feuding came to an "apparent end" because even though the Conservative Party achieved electoral success under its first leader, Stephen Harper, it always seemed this grand conservative coalition actually rested on a shaky foundation.

In other words, the various right wing clans and factions that made up the Conservative Party might have been marching under the same banner, but they still didn't necessarily like each other.

One even got the distinct impression that the only thing holding the Conservative party together was Harper's iron discipline.

At any rate, when Harper departed the political stage in 2015, the question of unity emerged once again.

As a matter of fact, the party's leadership race to replace Harper openly pitted the various ideological tribes against each other, with Michael Chong championing the Red Tories, Kellie Leitch, the populists, Brad Trost, the social conservatives and Bernier, the libertarians.

As a result, the leadership contest wasn't just about who would lead the party, it was also about answering a more profound question — what does conservatism mean?

Yet, at the end of the day that question was left unanswered.

In what was perhaps a compromise move, the Conservatives elected Andrew Scheer as leader, a man not strongly connected to any political dogma or to any ideological tribe.

But while Scheer's victory ensured peace in the short run, it also set the stage for turbulence in the long run, since the new Conservative leader lacks a strong ideological base in the party and also lacks Harper's ruthlessness.

In a party fraught with so many ideological fault lines, that's a recipe for trouble.

And speaking of trouble, this brings us back to Bernier.

Bernier has always branded himself as politician who promotes a purer brand of ideological conservatism and he wants the Conservative Party to also promote that brand of conservatism.

Thus when Bernier judged that Scheer was willing to compromise ideological purity on the altar of political expediency, he left the party, just as conservatives in the past left the federal PC party and the Alberta PC party.

Mind you, Bernier is just a single MP, so conservatism isn't yet facing another fratricidal conflict.

But if Scheer ends up alienating his base, those alienated conservatives now have a leader in waiting.

Photo Credit: Jeff Burney, Loonie Politics