Alberta's minimum wage goes up to $15 an hour October 1 and the business lobby is on the angry train to derail the hike.

Now sitting at $13.60 an hour, the province's minimum wage is second highest in Canada. The Oct. 1 hike will push Alberta to the top of the provincial heap.

But the Canadian Federation of Independent Business is sounding the alarm. The group wants a delay to assess what the hike will do to the provincial economy, code for 'let's delay it long enough for a likely United Conservative Party election win in the spring, thus completely kiboshing any increase.'

The CFIB cites its own poll of small business owners to argue that since the last hike to $13.60 business people have reduced plans to hire new workers and young people, eliminated some jobs and raised prices to the consumer.

Radio talk show hosts have been happy to jump on the issue, inviting CFIB's articulate director of provincial affairs Amber Ruddy to outline the concerns, particularly in the hospitality and food service industry, that the escalating wage has created.

"Hikes to entry level wages go too far, too fast and ultimately positions for young workers are disappearing," says Ruddy in a CFIB press release.

The number that oft times gets quoted is a City of Calgary report showing the loss of 25,700 service sector jobs in Calgary over the past year. The city gained in other sectors, however, for a net job loss of 9,200 in all sectors. There is no doubt Calgary has been sluggish on the employment front and is continuing to struggle with the deep economic dive it took in 2015-16, thanks to the faltering oil and gas sector.

All those empty towers on the downtown skyline in Calgary mean fewer well-heeled customers for city bars and restaurants, among the businesses most likely to be hit by the minimum wage increase.

So it's natural that the loudest voices on the call-in shows come from Calgary.

The minimum wage issue just doesn't seem to spark the same level of outrage in Edmonton, underscoring the difference not just in the politics of the two cities, (Edmonton went entirely NDP in the 2015 election and has a long history of centre-to-left politics) but now also in the economy of the two cities.

Edmonton never dipped as low as Calgary and is recovering at a fairly steady pace. The overall unemployment rate in Edmonton is 6.5, compared to 7.9 in Calgary.

In a province-wide call-in on CBC, John Rose, economist for the City of Edmonton, pointed out that while Calgary was shedding jobs, Edmonton gained, in total, 23,000 jobs in the past 12 months. He admitted accommodation and food sector jobs shrank slightly by 4,500 jobs but overall Edmonton's economy is not dealing with the same circumstances as Calgary.

For Alberta, minimum wage focuses right in on who's interests hold the day for the provincial political agenda. UCP and Alberta Party politicians are thumping for a halt to the Oct. 1 hike, predicting dire economic consequences.

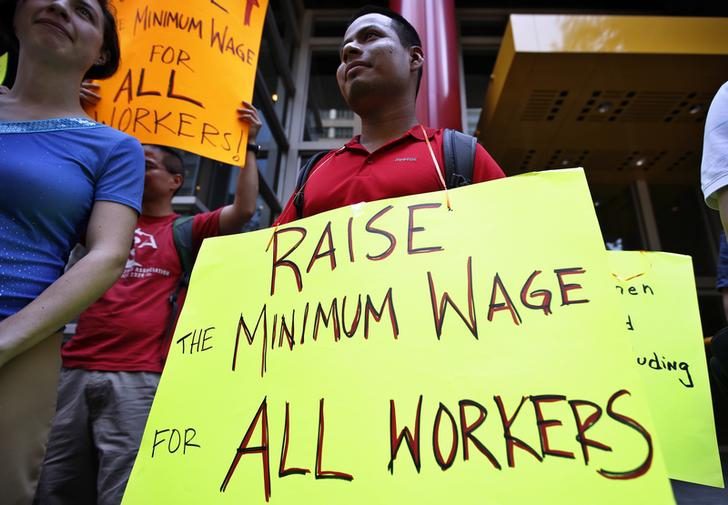

But for the NDP the issue is at the very core of their 2015 election platform. When Rachel Notley's government came to power in spring 2015 Alberta's minimum wage was tied for the lowest in the country at $10.20 an hour. The government swiftly put an annually stepped increase in place to culminate with this year's $15 rate.

Notley has been chiming in on Twitter in the past couple of weeks reiterating her government's determination to keep going.

"Who benefits from a higher minimum wage? It's women. It's single parents. It's families who are working more than two full-time jobs but who were still struggling to put food on the table and pay rent. We're not going to let working people get left behind," tweeted the premier.

The NDP argues Calgary's business malaise is not a function of a high minimum wage, which should puff up consumer spending while reducing historic wage inequities.

The relative health of Edmonton's job environment, not so dependent on the oil and gas economy, backs up the argument.

But for Calgary small businesses and their conservative backers, the NDP wage policy is an issue which will likely have strong legs through the fall and, they hope, into the spring election period.

It will be one of the issues that further define the different between Alberta's two largest cities, politically and economically, and might well be reflected in how the vote differs city to city.