For several decades now, it's been received wisdom of the Canadian commentariat that conservatives lose elections for basically only one reason: they run too far to the right.

From Preston Manning to Stockwell Day, from Danielle Smith to Tim Hudak, from Stephen Harper in 2004 to Stephen Harper in 2015, rare has been the conservative flop whose failure wasn't immediately attributed to a lack of appreciation for the supposed moderation of Canadian voters, and our alleged distaste for excessively "ideological" candidates.

Conservatives tend to find such analysis flippant, and darkly revealing. Notions that an excess of conservatism is what dooms conservative politicians implies watering down platforms is the only strategic advice Tory strategists need to follow, and casts the politics of the centre-left as an unambiguous moral baseline. For progressive journalists unshakably committed to their own politics, such uninterested critiques are the easiest thing in the world to offer.

Yet a curious thing has been happening lately, and it offers reason for cranky conservatives to pause. The press' standard "too ideological" criticism is once again resurfacing only this time it's Justin Trudeau's Liberal government taking fire for being too far to the left.

Most revealingly, the bashing is not coming from the Toronto Sun or National Post, but rather hoary figures of Laurentian establishment thinking, including the Globe's John Ibbitson, CTV's Don Martin, and the Toronto Star's Chantal Hebert.

The critiques hew to a shared narrative: Trudeau's declining poll numbers are the logical response to an unattractive administration obsessed with lefty pet causes — particularly postmodern gender theory — at the expense of much else. His is becoming a sanctimonious, judgmental government, cockily self-confident it's on the side of the angels and viciously contemptuous of those who don't share the conclusion.

The Liberals' far-left imperiousness is said to be manifest in everything from the summer jobs abortion test to the "peoplekind" mansplaining, from Service Canada's attempted abolishment of gendered prefixes to Minister McKenna's recent declaration that she has "no time" for anyone whose commitment to saving the planet is less pure than her own.

There is, to be sure, a noticeable "more in sadness than anger" vibe to much of this suddenly fashionable strain of analysis, a tone that implies the Trudeau government has been, before anything else, a disappointment to those otherwise inclined to carry water for it. Complaints that the prime minister's virtue-signaling stunts represent a waste of a majority mandate imply a more competent implementation of the Liberal platform would be a marked improvement. There is also an observable class interest at play — as Trudeau's political brand becomes more closely aligned with forces of political correctness who aim to censor language and opinions, it's predictable that such things will provoke disproportionate anxiety among the country's "mostly straight white male pundit class," as Loonie Politics' Dale Smith put it.

Yet regardless of motive, narratives matter a great deal in Canadian politics. In a small country where the number of people who keep active tabs on the Ottawa scene is low, and fairly geographically concentrated, it's easy to entrench storylines in the national consciousness about political strengths and weaknesses, and like all good stories, they're hard to forget once told. Narratives don't necessarily have to be true — conservatives would argue the "too right-wing" trope isn't — they simply have to sound plausible enough to inspire a reaction. The fact that Doug Ford is so weaselly-mouthed when it comes to cutting spending can be directly attributed to the folk wisdom that his party lost in 2014 by being too glib and heartless about budgetary cutbacks. The fact that he will get a pass from his base for doing so reflects their internalization of the tale.

As 2019 election season approaches (if we're not already in it) Prime Minister Trudeau finds himself increasingly pigeonholed in a story Canadians are not often told, begging a question that is not often asked: how liberal is too liberal? The ruling party has over a year to see if they can shift this hostile frame, perhaps by, as I suggested in a previous column, doing what they can to make the 2019 story about Andrew Scheer instead. Gerald Butts has certainly been trying his best, with loopy tweets attempting to link the Tory leader to white nationalism through a kind of "six degrees of separation" (the sequence, from what I can tell, goes like this: Scheer hired Hamish Marshall, Marshall was on the board of The Rebel, which is run by Ezra Levant, who hired Faith Goldy, who has since devolved into some kind of white supremacist), though this has also been taken as evidence that keeping a lefty crank like Butts on staff is more trouble than it's worth.

A more viable solution would be to fight narrative with narrative. During the 1990s, the Liberal Party helped consolidate a reputation as brilliant Bill Clinton-style "triangulators" of the best ideas of right and left, combining wise management of the economy with incremental social reform. It was an agenda of genuine "centrism," declared the press, and reviving this Liberal brand of Goldilocks pragmatism, which is taken to attractively contrast with the other two "ideological" parties, could breathe new life into an administration cast as fanatic and rigid.

Trudeau seems precisely the wrong man to reclaim this mantle, alas — his political instincts are not deep or strategic, and as someone who clearly relishes his self-appointed role as the world's social justice pope, one imagines the PM would be resistant to changing his personal brand this late in the game. Will it prove the pride before the fall?

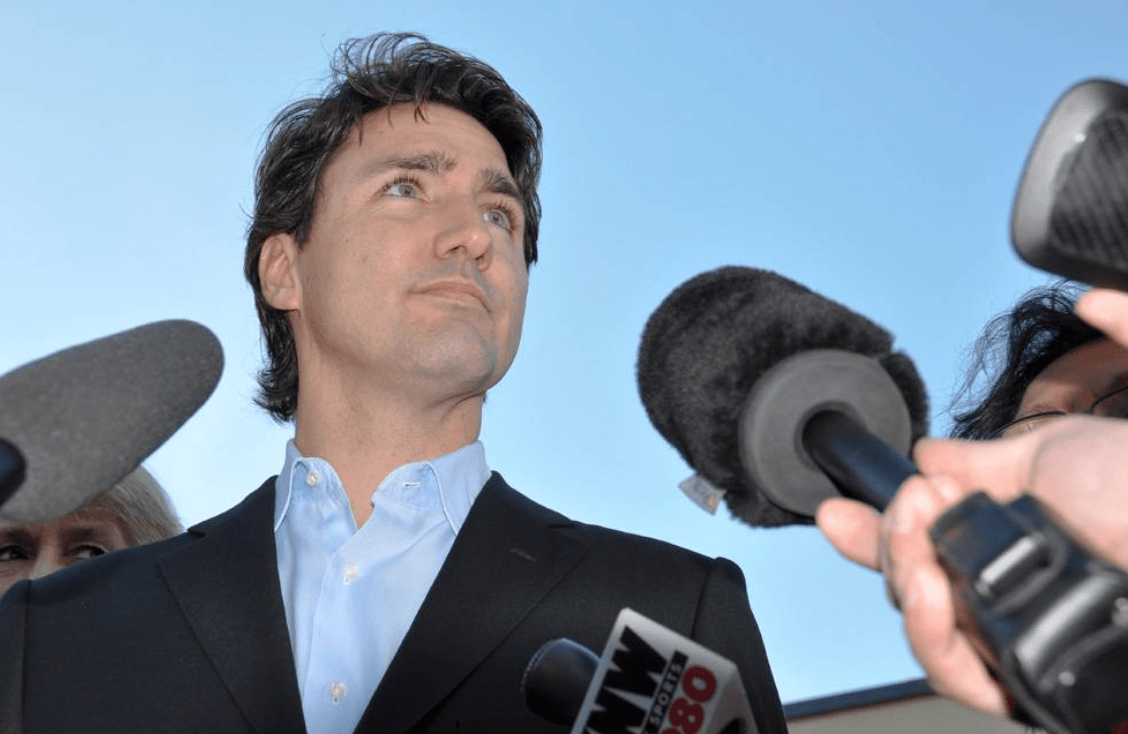

Photo Credit: The Georgia Straight

Written by J.J. McCullough