Speaking of his struggles with depression, last year famed young adult writer/vlogger John Green described mankind's unhelpful obsession with causal relationships.

"We need human lives to be narratives that make sense," he said, "So if we can't find causation, we just create it. Like, people get depression because they're weak, or people get diabetes because they don't eat well, or they have heart failure because they don't exercise. All that stuff is either totally inaccurate or overly simplistic, but we want every effect to have a cause, and when we can't find that cause we invent one."

His point was some things in life are the product of a multitude of complex variables, and thus don't have a single, magic cure because they don't have a single, magic cause.

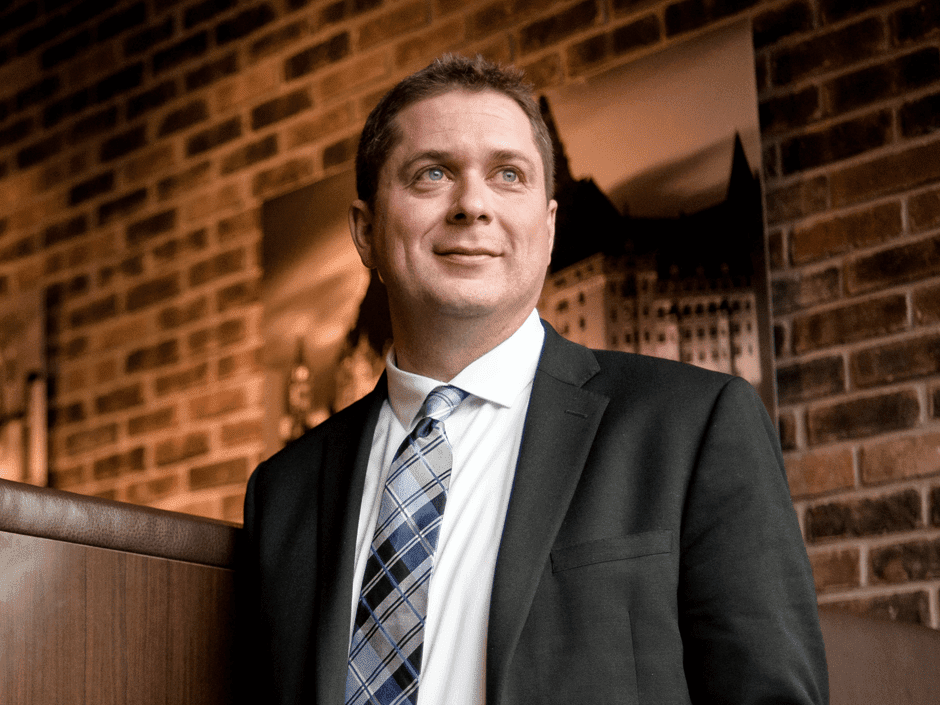

I was thinking about Green's words as I read a recent column by John Ivison in the National Post, which looked at Andrew Scheer's poor polling with millennials, and advised the Tory leader to overcome it by remaking himself as an aggressive foe of climate change. Ivison's logic (which in fairness, is hardly exclusive to him) presents political taste as a product of a clear causal relationship — in this case, the sorts of issues a particular demographic claims to care about, and the sort of policy prescriptions a politician or party offers.

But do people actually form their political tastes this way? Canada's conservative parties, at both the federal and provincial level, are a revealing case study, since almost all have worked so hard over the last decade to abandon their supposedly least attractive, most stereotypically off-putting positions, but have barely broadened their appeal as a result.

At one time, it was received wisdom that Conservatives were politically stagnant because they were hesitant about homosexuality, adversarial to abortion, and too… well, let's not mince words, racist, basically. In response, Stephen Harper was elected and reelected while strenuously refusing to relitigate the progressive status quo on same-sex marriage or abortion, running openly gay and unapologetically pro-life candidates, and even sending delegations to Pride parades across the country. Ethnic outreach, personified by Harper's so-called "Curry in a Hurry" immigration minister Jason Kenney, earned almost across-the-board praise.

Canada's provincial conservative parties all emulated Harper's example, or were even further ahead down a similar path. Today, issues involving LGBT rights, abortion, multiculturalism, and, for that matter, climate change, are even less contentious in provincial legislatures than in Ottawa.

And yet, when one looks at opinion polls across Canada, we still see conservatives failing to resonate with the very groups they changed themselves the most to appease.

Despite being headed by Patrick Brown, easily the country's most brazenly accommodating, fashion-following, conservative-in-name-only Tory leader, the Ontario PC Party still pulls its worst numbers from young voters, urbanites, and the highly educated. To be sure, the PCs still generally lead these demographics at the moment — a testament to the extreme unpopularity of the incumbent Liberal government — but they remain the most fragile backers of the provincial Tories and their carbon-tax endorsing, abortion-defending, transgender-bill-supporting leader.

My own province of British Columbia is an even starker study. British Columbia does not have a viable conservative party, which makes most consider the BC Liberal Party the "conservative" option by default. I don't like this classification, but it's very mainstream, so let's just play along. The BC Liberals adopted Canada's first carbon tax, appointed the province's first openly gay cabinet minister, backed anti-protest "bubble zones" around abortion clinics of the sort recently approved in Ontario (with Patrick Brown's approval, natch), and banned high heels in workplaces, among numerous other initiatives to demonstrate their forward-thinking bona fides.

They're still terribly unpopular with progressive voters. In the last provincial election, the Liberals were wiped out in all but the most conservative parts of BC. Last-minute polls indicated young voters preferred the NDP or Greens by margins of 10 and 20 points respectively, with similar gaps of alienation among urbanites and the highly educated.

What's clear, in short, is that a lot of Canadians are not voting for right-of-centre parties for reasons that can't be mitigated with changes to that party's platform or governing agenda. This is because political preferences are often not entirely rational things.

A lot of decisions we make in the voting booth come from deep-seeded beliefs that this-or-that party or politician just deserves our support more than their alternative. These tend to be deeply emotional feelings, bound up in intangible judgments of who we've learned to process as trustworthy through our particular cultural milieu, not to mention a fair bit of ignorant prejudice. There's been some research suggesting what David Brooks calls "partyism" — hatred of people with certain political beliefs, rationalized with cruel stereotypes — is one of the entrenched social ills of our time.

It's not without reason that elections in Canada, all things considered, are generally close and competitive, with a firm party system based around stable ideological tribes. At the next election, some minds will be changed at the margins and some seats will swap, but believing Andrew Scheer, or any leader, is simply one clever policy or marketing gimmick away from upending decades of ossified political culture is to engage in the hopeless naïveté of seeking easy explanation for our species' maddeningly inscrutable habits.

Written by J.J. McCullough