Left-of-centre elites in this country — by which I mean most politicians and journalists — enjoy assuming Canadians share their beliefs, yet rarely bother to verify if they actually do. A writer like Jon Kay, who recently wrote another one of his trademark essays stating with great confidence what "Canadians" feel about this-or-that, never fails to presume the ubiquity of his opinions, just like Prime Minister Trudeau whenever he gives a speech at some international forum making generous use of the pronoun "we."

Such taken-for-granted assumptions are generally flattering — we are a kind people, tolerant, polite, etc. — but also ideological. They tend to assume a population comprising nothing but liberals, where a progressive consensus on everything from health care to gun control to immigration forms an unshakable part of the national psyche.

I don't doubt Canadians who speak with this sort of confidence about their countrymen genuinely believe their generalizations. If you're wired tightly enough, it's not difficult to go through life only spotting evidence that reenforces your conclusions. The problem is self-delusion can become extraordinarily self-destructive when your professional success is tied to accurately reading the public mood, as the massive backlash to the Omar Khadr payout has ably demonstrated.

Whatever newfound "concerns" Justin Trudeau now professes to have about the $10.5 million he handed Mr. Khadr to avoid fighting him in court, it seems clear the prime minister and the people around him did not anticipate the decision to offer such a massive settlement would be as poorly received as it was. Doubtless, Trudeau and his handlers consume a mostly progressive media diet, reading the papers in which all the big columnists and reporters have spent years portraying Omar Khadr as a deeply tragic figure, unjustly screwed by the American war machine and the cruel Harper government. No doubt the prime minister genuinely believes his election was at least partially a referendum on softening the Islamophobic edges of the war on terror, with his opposition to nasty Conservative policies like stripping the citizenship of convicted terrorists broadly popular. Surely his party had convinced themselves that Canadians are such a permissive and progressive bunch that they would welcome — maybe even celebrate? — their government's generosity in showing Mr. Khadr just how compassionate Canada can be.

Unfortunately for them, one reality about Canadians that is very easy to prove, but completely absent from progressive conventional wisdom, is our general hard-heartedness on what could be called "law and order" issues. A poll I like to cite is a 2010 Angus Reid survey that asked Canadians, among other questions, what sorts of crimes convicts deserved to be executed for. 62% supported executing murderers, 31% supported executing rapists, 17% supported executing kidnappers, and 6% supported executing those convicted of armed robbery. Think about that for a moment — the number of Canadians who support executing kidnappers is roughly the same as the number of Canadians who voted NDP in the last election. The idea of executing murderers has a higher approval rating than just about any politician anywhere in the country. Yet how many people in Ottawa, or in privileged media jobs, would be likely to think "executing criminals" when conjuring up popular Canadian opinions?

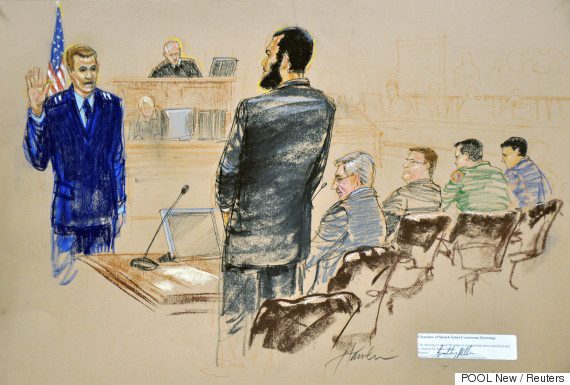

Omar Khadr was an al-Qaeda operative who participated in armed combat against US forces in Afghanistan — in other words, he fought with our enemies against our allies in a war in which Canada was (and still is) a combatant. He was captured, and held as a prisoner of war in Guantanamo Bay, and ultimately pled guilty to murdering Christopher Speer (and other terrorism-related charges), for which he served a prison sentence in Canada. Whatever other legal complexities of his case, these are the indisputable facts, and the evidence suggests most Canadians are not inclined to be compassionate in the face of them. A nation that supports executing murderers is not one eager to make them multi-millionaires, at least.

Nor are "we" particularly concerned with preserving the protections of citizenship to those who make war against their own country. A 2012 poll from NRG Research found over 80% of Canadians supported stripping citizenship from convicted traitors and terrorists, a sentiment which later became law through the Harper government's Bill C-24. (You may recall that this legislation was described as "controversial" by the press and opposition parties.)

Most Canadians clearly conceptualize citizenship as a privilege to be earned, as opposed to something that can be held indefinitely through an accident of birth, as was the case with Khadr, who lived barely a year in Canada before being shuttled back to Pakistan with his immigrant parents, themselves al-Qaeda traitors. The prime minister's famous quip that a "Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian" may make a good soundbite, and may well reflect the prevailing view of the legal establishment, but as a summary of national sentiment it could not be more ignorant.

What the Trudeau government has hopefully learned from Khadrgate — already evidenced by the prime minister's rapidly changing, increasingly defensive tone — is that confident liberal assertions about Canada do not become reality by virtue of repetition.

Canadians may well be very progressive in some ways, and on certain issues, appreciably more progressive than Americans (which is the only measure most care about). But there has never been much evidence to suggest the majority of Canadians have bought into what appears to be the elite consensus on crime and terror, namely that compassion is more important than punishment, and the legal status of citizenship infers victims a moral righteousness that can never be shed.

Written by J.J. McCullough