I fear the Trudeau government is embarking upon a radical transformation of Canadian democracy that will prove far more destructive than anyone realizes — including themselves. Because the Liberals' "democratic reform" agenda is being pursued with what appears to be the best of intentions, and because Canadian political reporters and commentators are broadly sympathetic to these motives, the real-world consequences for what's being proposed have received vastly less scrutiny than is deserved.

For starters, what has to be made extremely clear is that when we talk about electoral reform in Canada, what we are really talking about is reforming how we choose the prime minister. This is critically important because the Canadian system of government is more leader-centric than any other first world democracy, making the process of selecting that leader not one to be taken lightly. If Trudeau's reforms occur as predicted, our process of selecting the PM will become deeply unpredictable and chaotic.

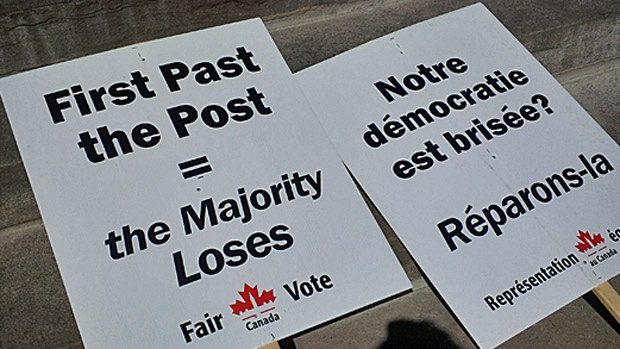

For the entirety of Canadian history, Canadians have understood their federal elections as proxy-votes on which party boss should be prime minister, with the PM-elect being the boss of whichever party wins the most seats in the House of Commons. The system is not perfect, and seems most unfair when the "most seats" is not an outright majority. Yet such outcomes occur only rarely.

Everyone agrees, however, that switching Canada's electoral system from first-past-the-post to a ranked-ballot regime of the sort the recently-struck, Liberal-dominated electoral reform committee is widely expected to recommend will make parliaments in which no one party holds a majority of seats the overwhelming norm. This, in turn, will chronically, instead of merely occasionally, make the prime minister of Canada a man or woman mathematically outnumbered in the House. The situation could become even more spectacularly undemocratic if so-called "coalition governments" become the norm as well, in which the prime minister may not even be the leader of the party with the plurality of seats, but the second or third-most — as Stephane Dion attempted in 2008 when he claimed a mandate to become prime minister despite a 66 seat gap and 11.4% difference in the popular vote between his party and the first-place Conservatives.

The other bubbling crisis is Trudeau's reformed Senate, in which new senators are no longer members of political parties, nor actively coordinate their actions with the prime minister.

It's not controversial to assert that Canada's appointed, arbitrarily-delegated Senate is a monstrous institution — its approval rating is usually in the single digits. Yet since the Supreme Court has declared that nothing short of a bundle of constitutional amendments can change it, what is the best way of making peace with its ugly existence?

The historic Canadian answer has been to make it a meaningless rubber-stamp, completely subordinate to the wishes of the country's democratically-elected prime minister. The Trudeau plan, by contrast, has begun the process of making the Senate subordinate to no one except itself. Trudeau has delegated the authority of Senate appointments to a panel he has only loose authority over tasked with making strictly non-partisan, and, evidently non-political picks. Trudeau is entirely correct that this will make the Senate more independent and engaged — the only problem is, there is scant evidence Canadians particularly want a chamber full of unelected university presidents, newspaper columnists, and wheelchair athletes actively engaged in making their laws.

From where we sit today, Trudeau's democratic reforms seem theoretical, and thus benign. Yet once implemented, they could prove the most dramatic consequences for Canada's system of government since Confederation. In a decade or so, the two most fundamental questions facing any democracy — who gets to be the leader, and who passes the laws — could cease having clear answers in Canada. We are on the brink of entering a new era in which our prime ministers will routinely be the leaders of widely-disliked second or third-place parties and legislation enjoying the broad support of a majority of MPs will routinely die at the hands of an unelected Senate taught to believe it enjoys a legitimacy previous Senates have not.

Canada's parliamentary system is badly designed, but over the last 150 years we have evolved traditions and customs to make it work in a manner that is at least predictable and accepted. It is this delicate architecture of conventions Trudeau proposes to dynamite, and too many have been too polite and optimistically naive to contemplate the frightening long-term consequences that will come from doing so.

Photo Credit: CBC

Written by J.J McCullough